Greek Debt Crisis: Does Anyone Find Greece's Bailout Deal Credible?

With deadlines looming for European lenders to reach a Greek bailout deal, an ironic situation has emerged: Under pressure to move reforms through his parliament, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, sworn foe of austerity, has become one of the foremost cheerleaders of the bailout.

Members of Greece’s creditor bloc, meanwhile, have cast serious doubts since the proposal was hashed out Monday. As discord grows, it now appears that no arm of the Troika, the three bodies that oversee the European bailout mechanism, stands fully behind the deal as written.

It used to be that Greece couldn't fall in line. Now things are changing. “What we learned in the last week is that not all the creditors are falling in line,” says Grégory Claeys, a research fellow at Bruegel, a Brussels think tank.

A paper leaked from the International Monetary Fund Tuesday called Greek debt “highly unsustainable,” raising concerns that the IMF would reject any final bailout plan that lacked substantial debt relief. An analysis from the European Union’s executive arm followed on Wednesday, concluding that “a very substantial debt re-profiling” might be needed.

As for the finance ministers that govern the third arm of the Troika, the European Central Bank, opinions are equally mixed. French minister Michel Sapin echoed the IMF’s view that Greece needs debt relief. His German counterpart Wolfgang Schäuble, the group’s most powerful member, has been frank in his belief that Greece cannot repay its loans. But he has scoffed at a potential debt writedown for the Greeks, and called the leeway for reprofiling “very small.”

If Greece passes reform measures, the Troika is expected to finalize details of the bailout in three of four weeks. But the general atmosphere of doubt surrounding the provisional agreement raises an uncomfortable question: Does anyone in the Troika really find the deal credible?

“A Big Blow To Germany”

Tsipras is only a grudging proponent of the deal. In a televised interview Tuesday he said that he signed on with “a knife at my neck.” In exchange for some 86 billion euros ($94 billion) in loans to keep banks solvent, Greece must undertake stringent structural reforms, raise value-added taxes, cut back on pensions and find 50 billion euros in assets to post as collateral.

The measures, many of which go against the politics of Tsipras’ left-wing Syriza party, must pass in parliament Wednesday for Greece to fulfill the first of its bailout obligations and avoid a Greek exit, or Grexit, from the eurozone. Tsipras, who has vowed to prevent a Grexit, casts the deal in its most favorable light. “We’ll ensure the burden is distributed with social justice,” he has said.

But the authorities that met Tsipras at the bargaining table have hardly been in lockstep. If anything, their differences have grown more pronounced since the 17-hour session to hammer out the deal concluded early Monday.

The IMF, in particular, has taken its displeasure to “a new level,” says Judy Dempsey, editor-in-chief of Carnegie Europe’s Strategic Europe. The international lender’s signals in the in the past week, she says, have been unmistakeable.

“The IMF was silent on Saturday, silent on Sunday, silent on Monday” -- days of crucial negotiations -- “and then came out Tuesday to say, ‘This just won’t do, it’s gone too far,’” Dempsey says. “This is a big blow to Germany.”

There are signs that the IMF has made its preferences known behind the scenes as well. In his first interview after stepping down, former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis emphasized that there were people "sympathetic" to Greece's position "at the highest levels" of the IMF.

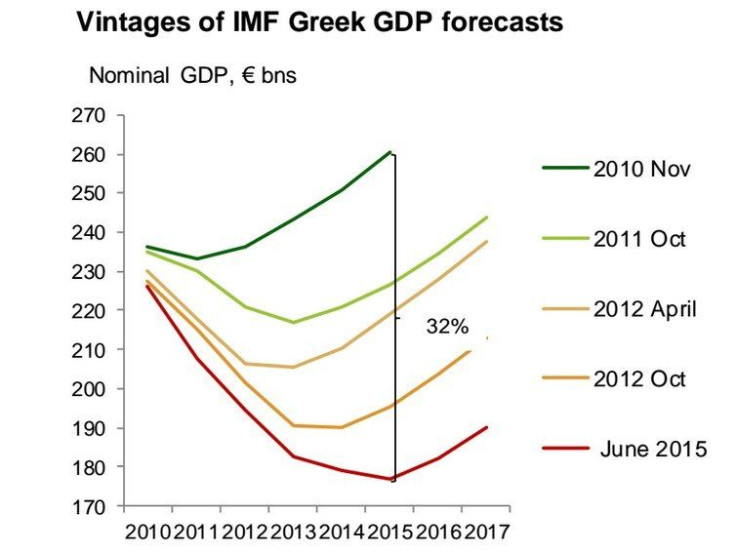

In its most recent analysis, the IMF predicted Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio to balloon to 170 percent by 2022, topping the ECB’s estimate of 150 percent. In previous years, both authorities have consistently overestimated the strength of the Greek economy.

The only sustainable options, the IMF said, would be a 30-year grace period on loan repayments, a debt haircut -- marking down the amount owed -- or, to the horror of Germany and like-minded countries, “explicit annual transfers to the Greek budget.”

Objectively, Germany’s finance chief doesn’t disagree. “Debt sustainability is not feasible without a haircut and I think the IMF is correct in saying that,” Schäuble told a conference July 9. But it’s a political non-starter. “There cannot be a haircut because it would infringe the system of the European Union.”

“Can’t Back Down”

Even the central arm of the Troika, the 19 finance ministers of the eurozone collectively known as the Eurogroup, has shown new signs of flagging trust and fraying cohesion.

In marathon negotiations over the weekend, the finance ministers reportedly laced into each other, airing grievances and trading recriminations. Though their differences are often minute, at root are differing philosophies around debt, forgiveness, and the purpose of the European monetary union.

Germany, with other budget hawks like Finland and Slovakia, believes in a rule-based system of economic governance that brooks little deviance from prior agreements. Debts must be paid, come what may.

This hardline stance has made a Grexit attractive to Schäuble and close to half of the German electorate. Germany is set to hold special parliamentary sessions over Greek financing needs this week. Prime Minister Angela Merkel remains publicly in favor of Greece staying in the eurozone.

France has pushed back on German intransigence, suggesting debt relief and softer austerity measures. “We cannot help Greece if we maintain the same debt reimbursement burden on the Greek economy,” Sapin, the finance minister, has said.

The Franco-German rift, says Claeys, exposes a deeper philosophical divergence in the eurozone that has been uncovered by the Greek crisis. “There are very strong disagreements between those two countries that were hidden for 25 years and are starting to emerge.”

Those differences don’t just bode ill for Greece -- they throw into question the entire eurozone project, which balances on the notion that sharing a single currency can unite a continent. “I’m quite pessimistic,” Claeys says.

For all the Troika’s disagreements, however, Dempsey finds it likely that its members will each hold their noses and eventually sign onto the proposal.

“They can’t back down, can they?”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.