Green-On-Blue, Fade To Black: Are Insider Attacks Drawing Down In Afghanistan?

It has been more than a decade since U.S. and allied troops rolled into Afghanistan to battle insurgents linked to al-Qaeda.

Violence is still rampant in the South Asian country of 35 million; ethnic divisions, political corruption and a still-active insurgency continue to threaten civilians’ safety. But a planned drawdown will have nearly all foreign forces out of the war-torn country by the end of next year.

International troops are still suffering casualties, even as the war draws to a close. For those soldiers, militant insurgents are not the only ones who pose a threat. Members of Afghan security forces, who are allies, are often the ones to point their guns at members of the coalition.

These insider attacks account for a significant percentage of ISAF deaths in Afghanistan; last year, the figure was 15 percent. The incidents are referred to as green-on-blue attacks, in accordance with a color-coding system used by the U.S. military where blue represents American forces and green represents allies. (Enemies are red.)

The frequency of insider attacks has become something of a yardstick for the international operation, which has the ultimate goal of entrusting Afghan troops with domestic security. As U.S. and other troops prepare to lighten their footprint, one question becomes increasingly important: Are green-on-blue attacks -- which should be inversely proportional to mission success -- on the decline?

It would seem so at first glance. The situation has certainly calmed down since 2012, which was the worst year on record for insider attacks.

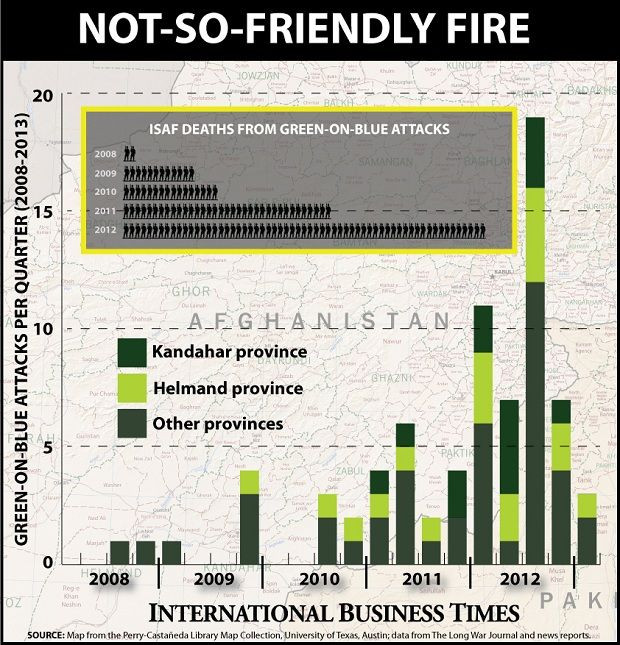

Figures from The Long War Journal, which uses military data and media reports to keep a running tally of attacks committed against foreign troops by Afghan police or military members, indicate that 44 insider attacks occurred in 2012, up from 16 the year before and five the year before that.

The 44 green-on-blue attacks last year killed 61 members of the international coalition currently engaged in Afghanistan, including troops and support personnel. 35 people were killed by insider attacks in 2011, and 16 in 2010. Helmand and Kandahar provinces are the most dangerous by far, followed by Kabul Province -- which includes the capital city of Kabul -- and Wardak Province.

Things were particularly bad in August of 2012, when 11 attacks spread across five provinces killed at least 15 coalition members. Lesser surges of green-on-blue violence were seen in April of 2011 and March of 2012.

The death toll certainly appears to be lower this year. Only three Americans, including one civilian contractor, and one British soldier have been killed by Afghan security forces (or people posing as Afghan security forces) in 2013. But if the past is any indication, violence comes in spurts. Three months of relative calm are not enough to project reliably into the future.

Furthermore, noted Long War Journal Managing Editor Bill Roggio, the apparent decline could simply be a result of having fewer coalition boots on the ground.

“The number of attacks is probably going to go down, but the question will be whether they go down proportionally as the NATO troops draw back,” he said. “There will be far less partnering and far less opportunities for the Taliban to conduct green-on-blue attacks.”

The International Security Assistance Force, or ISAF -- a NATO-led coalition established in 2001 -- has about 100,000 foreign troops on the ground in Afghanistan, according to their latest figures, about 68,000 of whom are from the United States. That’s down from its peak of about 140,000 troops -- including more than 100,000 Americans -- in 2011.

ISAF continues to wind down and train domestic forces to take the reins, and the time is fast approaching when Afghan officials will be forced to contend independently with the threat of insurgent violence.

The Taliban remains a serious threat. The militant Islamist organization ruled Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001, enforcing some semblance of order on the fractious country but also enforcing a harsh version of Shariah, or Islamic law, and committing human rights violations ranging from obstruction of aid to the perpetration of mass killings.

Both the Taliban and al-Qaeda have roots in the Soviet war in Afghanistan (1979-1989). Al- Qaeda’s focus is more global, but the groups have cultivated a relationship of mutual support and protection, which is why Afghanistan became the primary theater for the U.S. War on Terror after Sept. 11, 2001.

After more than a decade of conflict, the current U.S.-backed government in Kabul, led by President Hamid Karzai, is gearing up to take control of Afghan security despite concerns that the Afghan National Security Forces, or ANSF, may not be ready to enforce order on their own.

Recent statements from Kabul make it clear that the relationship between U.S. officials and Karzai is less than cozy. The Afghan president has called for American forces to leave the tumultuous Wardak Province, accusing troops of murdering and torturing innocent civilians there. Karzai also said on Sunday that American, European and Gulf State leaders were in cahoots with Taliban insurgents, an allegation that Chuck Hagel flatly denied in Kabul on Monday during his first overseas visit as U.S. defense secretary.

The insider attacks of 2013 -- two of which occurred within the past two weeks -- are just one more indication that ISAF and Afghan forces are not always on the same page. On Friday, three ANSF soldiers opened fire on Americans in Kapisa Province, killing at least one civilian contractor. On Monday, a local policeman opened fire on U.S. Special Forces personnel in Wardak Province, killing at least two Americans and two Afghans.

In both these incidents, the attackers were killed. That happens often, making it difficult to answer one of the most important questions regarding these incidents: Who, exactly, is behind most of the green-on-blue attacks? Are disgruntled Afghan security workers to blame, or is this the work of the Taliban insurgency?

The Pentagon has claimed that only 10 percent of green-on-blue attacks result from Taliban infiltration, though former ISAF Commander Gen. John Allen put a much higher cap on his own estimate, when he said in May of last year that “in analyses we have done, less than 50 percent of the ones that perpetrated these attacks were in fact Taliban infiltrators.” He later revised his figure to 25 percent.

But even Allen’s estimates may be lowballing it, since ‘infiltration’ is only one of several ways for Taliban and other insurgents to accomplish an attack.

A recently declassified document from U.S. Central Command, or Centcom -- the organization in charge of U.S. ISAF troops in Afghanistan -- highlights three ways for insurgents to perpetrate insider attacks. Infiltration, or joining security forces “with the intent to conduct an attack, collect information, obtain material, or create distrust/confusion” is one. Co-opting is another; it involves insurgents on the outside who “recruit or persuade existing ANSF members to conduct an activity by using intimidation, blackmail or connections.” There is also mimicking, which means that some insurgents “impersonate ISAF or ANSF personnel to conduct a quick attack by using uniforms of forged ID cards.”

Then there are legitimate insider attacks -- termed “destabilizers” in the document -- which result from “factors such as stress, mental instability, or drug use that cause an ANSF member to conduct a violent act against member of ISAF or ANSF.”

But Roggio estimates that the vast majority of green-on-blue attacks are perpetrated, directly or indirectly, by members of the Taliban.

“It’s a sign that the Taliban are still capable, and that they’re evolving their strategy,” he said. “These attacks are occurring while other types of attacks haven’t stopped. Suicide attacks are still happening, IEDs are still happening, assassinations are still happening, and the Taliban still control some areas within Afghanistan.”

Given this context, the apparent decrease in green-on-blue attacks offers little cause for optimism, especially since non-insider attacks also remain an issue. On Saturday, two bombs -- one in Kabul and one in Khost Province -- killed at least 18 people in total; the Taliban claimed responsibility for one.

Since 2001, the Afghan civilian death toll has surpassed 15,500, according to conservative estimates from Cost of War. ISAF casualties have surpassed 3,600. As 2014 draws near and foreign countries bring their troops home, optimism about the pursuit of peace in Afghanistan is running low.

But for coalition countries, domestic political and budgetary concerns seem to necessitate a drawdown. So the United States and its allies are determined to make the most of these final months to outfit and train Afghan forces.

“The fact is, any prospect for peace or political settlements -- that has to be led by the Afghans. That has to come from the Afghan side,” Hagel said after meeting with Karzai on Monday. "Obviously, the United States will support efforts if they are led by the Afghans to come to some possible resolution."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.