This Hacker Uncovered A Massive Police Surveillance Dragnet While Serving Time In Prison

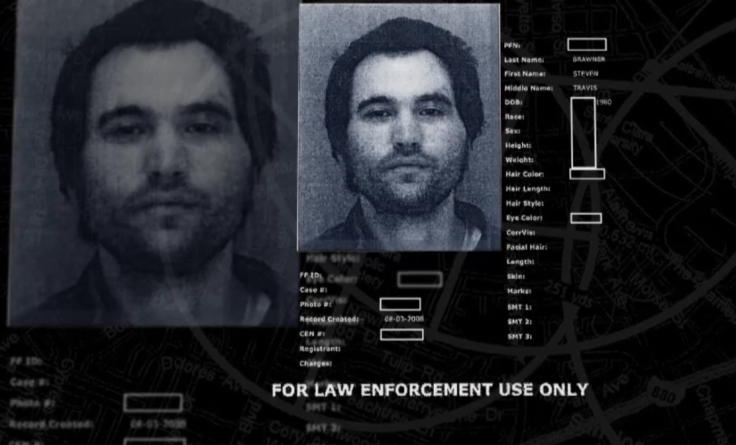

When Daniel Rigmaiden, a 27-year-old thief, was arrested by federal agents in March 2008, it was unclear how the feds actually managed to find his location and slap handcuffs on his wrists.

Though he's far from a household name, among investigators, Rigmaiden (and the various aliases he operated under) was a notorious identity thief who had bilked the federal government out of $3 million in fraudulent tax returns. But for years, the feds couldn't find him. Rigmaiden was brilliant at covering his digital tracks and eluding the law. And in the physical world, he lived off the grid too, camping for months at a time in the woods in Northern California.

For years, the feds say, it was a game of “catch me if you can.” And internally, federal investigators referred to him as "the Hacker" (though he was never convicted of hacking-related crimes).

Once Rigmaiden finally landed in police custody, however, the young thief decided to look into how the feds actually found his location. And that’s when he made a startling discovery: Police secretly used controversial cell phone spyware called “StingRays” to find his (and many others) location. This finding would later spark a fierce, national debate about privacy — and the extent to which law enforcement can use this sort of a device without a warrant.

Now, Rigmaiden's discovery is also the subject of a television documentary, “Truth and Power,” airing Friday on Pivot.

Though StingRay technology has now been widely reported — and even debated in the halls of Congress — the film details the unlikely series of events that turned a criminal identity thief into a Snowden-esque whistleblower who uncovered a highly contentious law enforcement surveillance technology. The devices, which are manufactured by the Florida-based Harris Corp., are about the size of a briefcase, but their power belies their stature.

More than collecting just a cell phone's metadata or location, the StingRay can intercept any and all communications on cell phones within a given range. They can be placed on squad cars, into backpacks or even mounted on a fixed structure like a control tower. No one knows just how many police agencies have the devices, but the American Civil Liberties Union, prompted by Rigmaiden's discovery, is hoping to find out.

In 2014, the ACLU launched a nationwide search for police departments that own StingRays. So far, they've found 59 agencies in 23 states and the District of Columbia. Still, that number may be much higher — the researchers say they are limited by the fact that “many agencies continue to shroud their purchase and use of StingRays in secrecy.”

All of their efforts, however, began because of Rigmaiden — a convicted felon serving time in an Arizona prison.

“Daniel clearly was a criminal,” says Brian Knappenberger, the show’s executive producer. "Nobody disputes that. ... But when he makes this discovery, he meets this broader community that’s fighting for [privacy] rights, and by the time he’s actually [out of jail], he’s still completely obsessed with it. And he believes the technology is wrong. And that it’s wrong for the public.”

Sitting in his jail cell, Rigmaiden pored over the legal documents of his case. He tried to make sense of how this StingRay device worked to find his location. His research led him to understand the devices “spoof” nearby cell phone towers, and essentially trick a cell phone into feeding data to whoever owns the StingRay. As he would later learn, the tool initially was developed by the military, but increasingly found its way into the hands of local law enforcement and the FBI for routine investigations.

Once he made this discovery, Rigmaiden began reaching out to well-known privacy experts, trying to persuade them to get interested in his case. Rigmaiden felt there was a serious privacy breach happening — but most people he contacted figured he was a lunatic.

“You have this guy claiming that the government used a secret surveillance technology to send signals through the wall of his house to track him,” Christopher Soghoian, the principal technologist for the American Civil Liberties Union, says in the film. “This is straight-up paranoid conspiracy theory stuff.”

Still, Soghoian decided to look into Rigmaiden’s claims. Because StingRays can’t be used to target just one individual, they often sweep up lots of people’s cell phone data. As a privacy advocate, Soghoian was shocked. “There’s no way to use it like a scalpel,” he says. “It’s like a huge trawler net. This is a technology that scoops up information about mostly innocent people.”

Since Rigmaiden’s discovery, StingRays have attracted national scrutiny. In 2015, Rep. Jason Chaffetz, R-Utah, introduced a bill in the U.S. Congress that would prohibit law enforcement from using StingRays without a warrant. Recently, the House Subcommittee on Information Technology held a seminar to analyze the use of StingRays and devices like them.

Courts are also examining the legality of their use. In fact, the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals will consider a 2013 case in which a Milwaukee man was located and arrested by local police with help from the FBI. “There is very strong evidence to suggest that he was apprehended through the warrantless use of a StingRay,” Ars Technica noted.

To be sure, law enforcement agencies say the devices are used to apprehend the bad guys — and by limiting their use, privacy advocates could let murderers and other criminals escape the law. The FBI, euphemistically, refers to StingRays as “network investigative techniques,” for instance.

Despite Rigmaiden’s discovery, it was not enough to convince a judge police infringed on his rights. In 2014, after 68 months in custody, Rigmaiden pleaded guilty and was released on time served. After his release, Rigmaiden became a passionate privacy advocate. In 2015, he assisted the ACLU in creating a “tutorial” on how defense lawyers can challenge StingRay use. He even helped Washington state legislators craft a privacy bill related to StingRay use, which was signed into law May 11.

Ultimately, Knappenberger says the film is about an unlikely hero for privacy rights — a 'hacker'-criminal-turned-whistleblower.

“The guy is on a mission,” says Knappenberger. “He’s on a crusade to end this technology. And the direct benefit to him has long since passed. He’s clearly emerged from this kind of bad situation as a whistleblower — someone who is taking on the system for the best of reasons.”

Knappenberger added, “When you think about these incredibly invasive surveillance tools getting in the hands of local cops who may not even know how to use them, or may not understand the broader constitutional protections, it’s really something to be concerned about.”

The episode of “Truth and Power” airs on Feb. 5 at 10 p.m. EST.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.