Haiti Racing To Rebuild Schools Destroyed In Earthquake

Haiti is struggling to send children back to class amid the devastation of the earthquake last month that killed more than 2,200 people and destroyed tens of thousands of buildings, including many schools.

It is a logistical and humanitarian challenge in the disaster-prone country -- the poorest in the Americas -- one that never fully recovered from the huge quake in 2010 that killed more than 200,000 people and caused billions in damage.

Classes for most students, initially scheduled to start September 6, have been pushed back by two weeks. And they have been postponed until October 4 in the three southern departments hardest hit by the 7.2 magnitude quake of August 14.

In those areas, many families lost everything.

Word of the delayed start to the school year launched a countdown for aid workers, who have raced to help the very needy people in the southern departments.

"Of the 2,800 schools in the three affected areas, 955 have been assessed by the government with support from UNICEF, and the first results show that 15 percent of them were destroyed and 69 percent were damaged," Bruno Maes, head of UNICEF in Haiti.

"It is going to be a race against time because it is just a few weeks to set up protective, safe learning shelters for children in these three departments so they do not miss another school year," Maes said.

The 2019-2020 school year ended in March of last year because of the Covid-19 pandemic. The following school year was then disrupted for many Haitians by widespread violence from powerful street gangs.

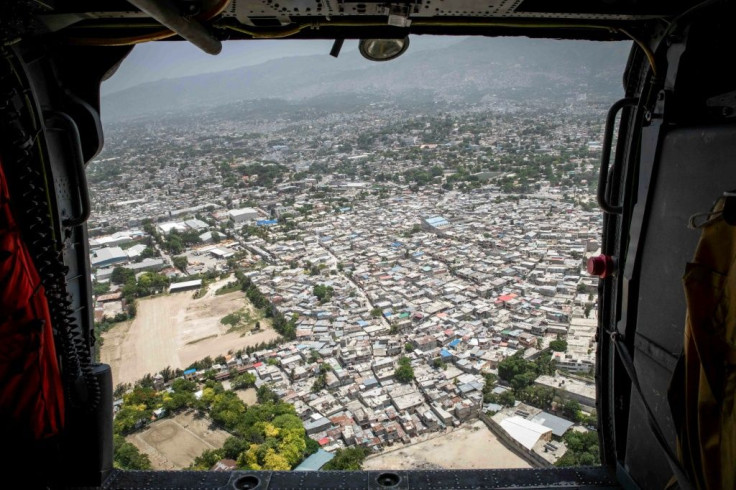

In late 2020 and early this year, gang members carried out many kidnappings for ransom, abducting children or teachers near schools in the capital Port-au-Prince.

About 150 kilometers (90 miles) from Port-au-Prince, the crime wave largely spared Camp-Perrin, but the area was hard hit by the quake.

Welcoming children back to school is a particular headache for private schools, which account for 80 percent of the schools in Haiti.

"We have students who have not yet paid their tuition for the 2017-2018 school year," said Maxime Eugene, a teacher at Mazenod high school. "We cannot send them home and make them miss a year of school over money," he said.

The quake destroyed every classroom in that well-known Catholic school.

Soldiers have cleared away the debris but school officials are still waiting for help to get the scholastic year going.

"Promises have been made to us but they have not yet been kept," said Eugene.

"If we get tents in time we can be ready for the start of school on October 4, because we were able to salvage the furniture," added Eugene. He insisted he is optimistic despite the prospect of having to teach on the school's football field.

The L'Asile district, tucked away in the mountain range that runs across Haiti's southern peninsula, was among the worst off after the August 14 quake, leaving residents desperate.

"The building might be ready, but I personally do not know how I am going to get back to work," said Brenus Saint Jules, an elementary school principal whose home was destroyed in the temblor.

The day after the quake, a neighbor lent him a pair of pants. And he spent the next 10 nights sleeping in the back of a truck with his wife and two grown children, along with four other people left homeless.

Saint Jules, 60, now lives under a crude shelter made of sheet metal. He can barely think about the coming school year.

The stress and drama of recent weeks have left him feeling "mentally ill," he said. "I spend my time thinking about how I am going to recover."

A teacher for more than 30 years, Saint Jules takes consolation from the fact that the school he has overseen for 12 years was only damaged and not altogether ruined. Still, he is a mess.

"I have become poor like the people who do not work," he said. "It is really hard from a human standpoint."

He continued: "But from a material standpoint, if the building is repaired, if the government intervenes to help parents, to help teachers, we can open the school on October 4."

And that despite the fact that Saint Jules, like most of his 400 students, now lives outdoors.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.