Hollywood Studios Are Self-Censoring Movies To Appease Communist Censors In China, Says US Report

For years, foreign-trade proponents have asserted that the power of capitalism and allure of the free market would inevitably bring U.S. values to China. But judging from one of the most popular U.S. exports -- Hollywood movies -- it turns out the reverse may be true.

As studios grow more dependent on ticket sales from the Chinese box office, filmmakers have become more willing to sanitize the content of their movies in order to appeal to the stringent sensibilities of Chinese censors. The People’s Republic of China, far from embracing the cultural mores of Hollywood, is actually changing the political complexion of American movies.

That’s according to a critical new staff report from the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, a congressionally mandated body tasked with monitoring bilateral trade between the United States and China. The 16-page report, released Wednesday, paints an unnerving picture of the Communist country’s tacit but diffuse influence over Hollywood’s biggest blockbusters, illustrating how some studios are now so fearful of being denied distribution in China that they readily tweak lines of dialogue, alter scripts and revamp entire scenes to make them more palatable to the country’s tastes.

“Ultimately, due to the limit on foreign films and the size of the market, U.S. filmmakers have significant motivation to work with Chinese regulators, even if they have to remove important scenes or themes from their movies to do so,” wrote Sean O’Connor and Nicholas Armstrong, the two research fellows who authored the report.

Political Themes Altered

Although studios have long released different versions of movies tailored for specific foreign markets, the trend, where China is concerned, has moved beyond postproduction edits and into the realm of willful self-censorship, according to the report. Often, alterations are discussed during production or while a film is still in development, with studio executives sometimes butting heads over how much, or how little, to soften a film’s message, modify its political themes or eliminate content that could be perceived as painting China in a negative light.

Such changes can be as simple as removing a potentially offensive reference to China (as the filmmakers of the zombie-apocalypse film “World War Z” reportedly did), to scrapping an entire scene featuring the destruction of the Great Wall, which was one of a number of changes executives at Sony Pictures made to the Adam Sandler disaster film “Pixels,” according to emails leaked last year as part of the cyberattack against the studio. Other examples noted in the report include the 2012 remake of “Red Dawn,” in which the invaders were changed from Chinese to North Korean.

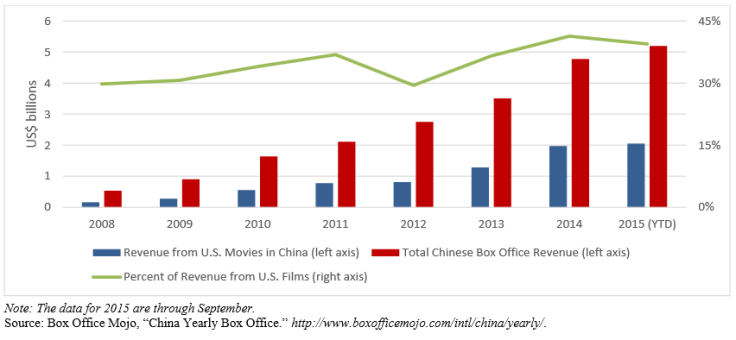

The reasons behind such concessions are self-evident to anyone who follows the money. While the crash of the Chinese stock market had dominated news cycles over the last few months, the country’s box office is growing at a staggering rate, and audiences there tend to gravitate toward Hollywood’s big-budget, effects-laden spectacles. Ticket sales in China generated $4.82 billion in 2014, a 36 percent increase from the previous year. And some analysts expect the country will surpass the United States to become the world’s largest movie market within three years.

Hollywood movies, meanwhile, account for about 15 percent of China’s box-office revenue, more than double what they did in 2012, according to data from Box Office Mojo. The cardinal sin of offending Chinese censors can cost a studio millions, as was the case with Disney’s “Captain Philips,” which fell $9 million short of projections after Chinese regulators opted to reject the film because of its overtly positive depiction of the U.S. military.

But in the rush to sanitize their films for the sake of distribution in the Chinese market, studios are by extension censoring the political themes of films for American audiences and curtailing the free-speech rights of directors, writers and actors. “Beyond the censorship of content for its own citizens, China’s broad prohibitions impact content presented worldwide,” O’Connor and Armstrong wrote.

WTO Violations?

The report suggests that China’s stringent regulation of American movies isn’t just a matter of cultural differences, but in fact runs afoul of China’s commitments to the World Trade Organization, which in 2007 ordered the country to open its doors to cinematic imports. China failed to comply with the WTO directive for several years, the researchers write, but in 2012 made a deal with the United States to raise the cap on film imports from 20 to 34 films a year -- a move heralded by the Obama administration as a breakthrough.

But more films didn’t lead to WTO compliance. “The ruling called for China to provide equal rights for all individuals and enterprises, both foreign and domestic, importing entertainment products to China on an unlimited basis,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers go on to cite a 2014 report from the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, which found that two years after the U.S.-China deal was finalized, China had still not taken “concrete steps” to further open the market. China’s film industry doesn’t have a system equivalent to the MPAA’s movie ratings. But its State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television of the People's Republic of China -- SAPPRFT -- has broad discretion to block content deemed by censors to be culturally offensive.

Wednesday’s report further substantiates what some media commentators have been saying for some time: that China’s burgeoning market power is giving the Communist Party undue leverage over American entertainment.

“The Chinese censors can act as world film police on how China can be depicted, how China's government can be depicted, in Hollywood films,” Ying Zhu, a professor of media culture at CUNY’s College of Staten Island, told NPR in May. “Therefore, films critical of the Chinese government will be absolutely taboo.”

Read the full report, “Directed by Hollywood, Edited by China,” here.

Christopher Zara covers media and culture. News tips? Email me . Follow me on Twitter @christopherzara .

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.