Homo Naledi: South African Cave Yields A New Species Of Ancient Humans

The “Cradle of Humankind” -- a Unesco World Heritage Site located approximately 30 miles north of Johannesburg, South Africa -- is famous for its rich and diverse deposits of ancient hominin fossils. Now, this region, crisscrossed by vast cave systems, has yielded a huge trove of fossilized bones belonging to a hitherto unidentified species of the early human lineage -- the Homo naledi.

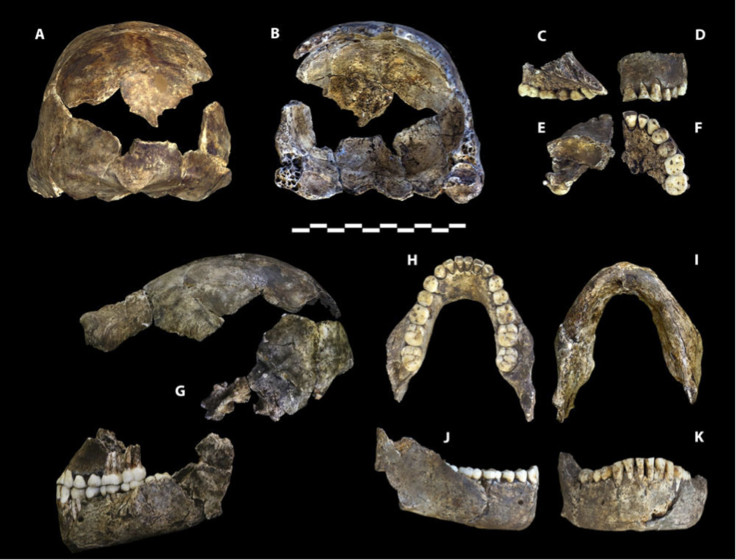

The discovery of 15 partial skeletons, composed of 1,550 distinct specimens, was announced Thursday in the journal eLife and at a press conference in the Cradle of Humankind. The researchers claim that the discovery -- which is the largest sample discovered at a single African site, and one of the largest anywhere in the world -- is significant enough to change our understanding of human evolution.

“What we are seeing is more and more species of creatures that suggests that nature was experimenting with how to evolve humans thus giving rise to several different types of human-like creatures originating in parallel in different parts of Africa,” Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum, one of the peer reviewers of the paper, told the BBC.

The fossils of the creature, named after the Rising Star cave system in which they were discovered -- “naledi” means “star” in the local Sesotho language -- paint the picture of an ancient hominin that possessed a mixture of human and ape-like traits.

In the paper published in eLife, the researchers describe Homo naledi “as being similar in size and weight to a small modern human, with human-like hands and feet.” Furthermore, while the skull has several unique features, it also has a small braincase that is most similar in size to other early hominin species that lived between four million and two million years ago.

As of now, the Homo genus is believed to be about 2.8 million years old, with Homo habilis being its earliest species. If the bones are almost as old, the naledi species must have evolved near or at the root of the Homo genus.

However, because of the nature of the chamber sediments and the lack of other animal remains at the site, the researchers have not yet been able to nail down the exact age of these fossils, without which “there’s no way we can judge the evolutionary significance of this find,” Rick Potts, director of the human origins program at the Smithsonian Institution's Natural History Museum, who was not involved in the discovery, told the Associated Press.

Another aspect of the discovery that has raised questions over our current understanding of human cognition and behavior is the location where the bones were found.

The fossils were found in an extremely hard-to-reach chamber of the caves, accessible only through a series of complicated pathways -- some of which were as narrow as 8 inches. According to the researchers, the location of the discovery suggest that early hominins might have intentionally deposited bodies of their dead in a “burial chamber” of sorts -- a “ritualized” behavior previously considered limited to modern humans.

“We are going to have to contemplate some very deep things about what it is to be human. Have we been wrong all along about this kind of behavior that we thought was unique to modern humans?” Lee Berger, the American paleoanthropologist, who led the team that made the discovery, told the BBC. “Did we inherit that behavior from deep time and is it something that (the earliest humans) have always been able to do?”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.