Housing Market 2015: Despite Real Estate Rebound, Millions Of Minority Homeowners Are Still Underwater

The housing crisis hit few people harder than LaDonna Foster. A secretary for the city of St. Louis, Foster divorced in 2007 and soon went into bankruptcy. Two years later she had a heart attack. In the intervening years, her home, which she bought in 2001 for $73,000, fell in value to under $50,000.

Foster was left paying off her original mortgage along with cascading medical debts. Especially painful was the fact that she'd refinanced her home just before the downturn, effectively adding to her debts. “I always tried to make sure that my home was my first priority, but sometimes you just can’t,” she says.

Foster defaulted for a second time and to her creditors pleaded for relief. “You have to fall at their feet for mercy,” she recalls. She managed to secure a loan modification, and now she's scraping by.

But at 48, Foster is an underwater borrower: She owes more on her mortgage than her house is worth. Today, Zillow values her home at $47,825, more than $25,000 less than what she bought it for. Unable to move without taking a heavy financial hit, Foster is stuck paying far more than she should for a home she can barely afford to maintain.

The foreclosure epidemic fell particularly hard on segregated North St. Louis County. “It was like a bomb went off in the neighborhood,” says Linda Ingram of Beyond Housing, a St. Louis community development nonprofit. “There are still pockets where it hasn’t come back at all.”

Despite upbeat housing reports, economists increasingly worry that the communities like those of North St. Louis that were hit hardest in the recession -- poorer, predominantly African-American and Latino neighborhoods -- may have missed the housing recovery for good.

George Washington University sociologist Gregory Squires sees demographic fissures in the housing market that aren't likely to subside anytime soon. “The narrative that the crisis is over is really premature.”

Trapped Underwater

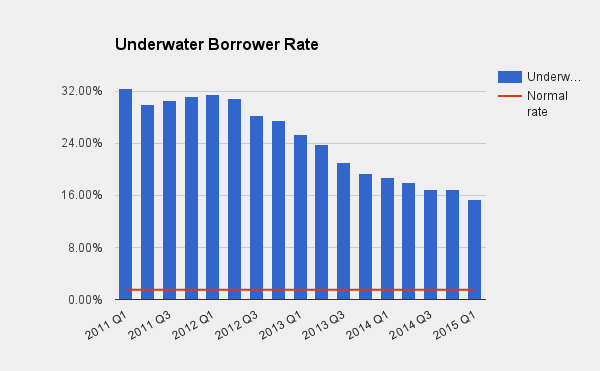

The most recent housing data indicate that in many communities, high underwater mortgage rates have become entrenched. Even as housing prices rise for their fourth consecutive year, the decline in underwater mortgages has stalled out at levels that economists estimate is 8 to 10 times the rate a normal market should endure.

According to a report from housing data company Zillow, the share of mortgages that are underwater notched down to 15.4 percent from 16.9 percent, where the rate had held constant for the previous two quarters. It’s down from a post-crisis high of more than 30 percent, but still far in excess of historical averages. Nationwide, nearly 8 million homeowners are still underwater.

And the data show sharp disparities in some cities. In Atlanta, 46 percent of lower-income borrowers are underwater, compared with just 10 percent of higher-income homeowners. Nationwide, low-end homes are three times more likely to be underwater than high-end homes.

The negative equity rate -- the percent of mortgages that exceed the value of underlying properties -- is an important indicator of housing market health. Homeowners trapped in underwater mortgages are disinclined to move. This freezes home sales and makes it harder for borrowers to build equity in their houses -- the primary store of family wealth in the U.S.

Other effects are not so visible. Debts weigh heavily on household finances, putting a damper on spending and putting investments like college tuition out of reach.

Svenja Gudell, senior director of economic research at Zillow, explains that rising home values helped bring millions out from underwater in the past few years. But that trend is fading as home price appreciation slows from brisk double-digit clips to a crawl. “Some homes are actually experiencing home value decline,” Gudell says. “We really didn’t have that before.”

Left Behind

As the larger housing market plods forward, the communities left behind fit a familiar profile: low-income, nonwhite and struggling with unemployment. Targeted with aggressive loans before the crisis, these neighborhoods are now thirsty for investment.

The trouble these communities have finding relief reminds some of the postwar practice of redlining, or shutting off black and Latino areas from bank services. “These communities were redlined for decades, and then when the crisis happened, they were ripe for predatory loans,” says Squires. “Now we’re seeing a return of old-fashioned redlining.”

A report Squires co-authored last year, titled “Underwater America,” pinpointed the 395 zip codes with the highest negative equity rates. In 64 percent of these, African-Americans and Latinos made up at least half the population. Thirteen of the zip codes fell in North St. Louis, including Ferguson, the site of popular unrest last year over policing and racial discrimination.

Since the report was published in early 2014, the situation in some cities has worsened. In Kansas City, Missouri, 43 percent of low-end mortgages were underwater in the previous quarter, up from 38 percent the year before. In Pittsburgh, the negative equity rate for bottom-tier borrowers notched up 5 percent. St. Louis saw its overall negative equity rate improve, while those in the lowest income brackets sank further underwater.

A New Normal

The situation may not be as dire as it sounds. For some, being underwater isn’t a pressing concern. Eventually, they hope, markets catch up. “We see homeowners willing to continue paying a $125,000 mortgage for a home that’s worth $25,000,” says Ingram.

But if home prices stall, the challenges for these communities will grow only steeper. Government support is flagging. The largely successful Home Affordable Refinance Program, a federal mortgage-relief effort, has benefited 3 million homeowners but is open to only some 600,000 more. A patchwork of various other programs has helped, but their impact is limited.

“There’s going to have to be some policy action because currently there really aren’t any options,” says Zillow’s Gudell.

In the absence of a policy solutions, the market is settling into a historically novel state of affairs, with wide swaths of American homeowners trapped paying more on their homes than they are worth.

Foster sees little hope of a turnaround. A foreclosed house down the block just sold for $38,000. “Half of these houses are not worth what they used to be,” she says.

Recently, Foster won a principal reduction on her house; her mortgage is now at a more attainable $55,000. Her monthly payments also came down to more manageable levels. But, she concedes, the house remains underwater. “Why sell when you can just live in there until you fall down?”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.