How To Build A $100,000 Portfolio -- Or An Even Bigger One

Perhaps you're sitting on several thousand dollars of debt and with a thousand dollars or less in the bank. The idea of having a portfolio worth $100,000 (or more) may seem impossible -- but it's not. You're not going to build great wealth with the money market or in savings accounts these days, so take some time to learn about stocks, which offer higher returns and can build amazing wealth.

Even if you already have a portfolio worth $100,000, you may be surprised at how much bigger it can get: Becoming a millionaire is very possible for lots of unsuspecting Americans. Here's a guide to vastly improving your future financial security.

Your soon-to-be $100,000 portfolio will likely consist of some or all of these investments:

- Index funds

- Managed mutual funds

- Individual stocks

- Dividend-paying stocks

But first, a pep talk

If you're struggling to make ends meet today, don't assume that you're destined to be financially insecure forever. With some learning and determination, you can turn your financial life around. And if you're not in dire financial straits now, these tips can turbocharge your portfolio's growth.

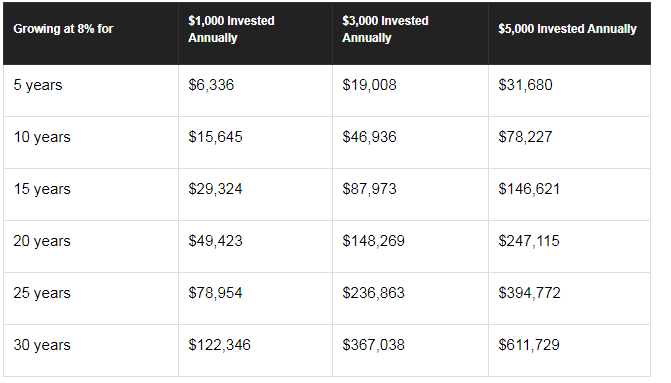

A $100,000 portfolio is surprisingly attainable -- especially if you're many years from retirement. You can amass more than $100,000 by investing only $1,000 per year. It will take decades, though, if your dollars grow at an annual average of 8%. You could do it in only 17 years if you're socking away $3,000 annually -- and annual investments of $5,000 could get you to $100,000 in just 12 years. (An 8% growth rate is used here in order to be a bit more conservative than the market's long-term average annual growth rate of close to 10%.)

You can, and should, do even better: A million-dollar portfolio

In reality, $100,000 won't get you as far as you need to go in retirement. Social Security will help, but the average monthly benefit check was recently just $1,461 -- or about $17,500 per year.

How much per year will a $100,000 portfolio get you in retirement? If you use the flawed (but still useful) 4% rule, withdrawing 4% of your nest egg in your first year of retirement and adjusting further annual withdrawals for inflation, you'll get just $4,000 in your first year -- only $333 per month. That's not going to cover living expenses for most retirees, even once you add in Social Security benefits.

So, how much do you need for retirement?

The answer depends on many factors, but you can invert the 4% rule to get a very rough idea. Here's how that works:

Imagine your goal for income in retirement is $60,000 per year, and you expect to collect $25,000 from Social Security. That leaves a shortfall of $35,000. Multiply that shortfall by 25 and the result will be the size of the nest egg you'll need in order to generate $35,000 in income in your first year of retirement. The answer: $875,000. The 25 is a result of dividing 100 by 4. If you wanted to be more conservative and withdraw only 3.33% of your nest egg in your first year, you'd divide 100 by 3.33 and would get 30. So you'd multiply your desired income by 30.

While $875,000 is a lot more than $100,000, it's also less than a million. It's not an exorbitant, out-of-reach sum for most people.

For inspiration, consider these people in ordinary jobs who managed to amass millions:

- Gladys Holm: Holm, a secretary, never earned more than a salary of $15,000, yet by paying attention to what stocks her successful boss was buying and selling, and often doing the same, she was able to bequeath $18 million to a children's hospital.

- Sylvia Bloom: For 67 years, Bloom was a secretary at a law firm and made many investments alongside her boss. She ended up with more than $8 million.

- Monsignor James McSweeney: Earning a sub-poverty-level income for decades as a Catholic priest, he focused on his investments in his free time, and was worth nearly $1 million when he died.

- Genesio Morlacci: This part-time janitor and dry cleaner left $2.3 million to Montana's University of Great Falls when he died at the age of 102.

- Thomas Drey, Jr.: The retired teacher spent a lot of time researching companies at the Boston Public Library. Upon his death, he gave the library one of its biggest gifts: $6.8 million.

- Jay Jensen: Another retired teacher, Jensen lived frugally, investing steadily in blue-chip stocks for some 40 years. He never earned more than $47,000 per year at his teaching jobs, but he turned that into several million dollars, most of which he gave away.

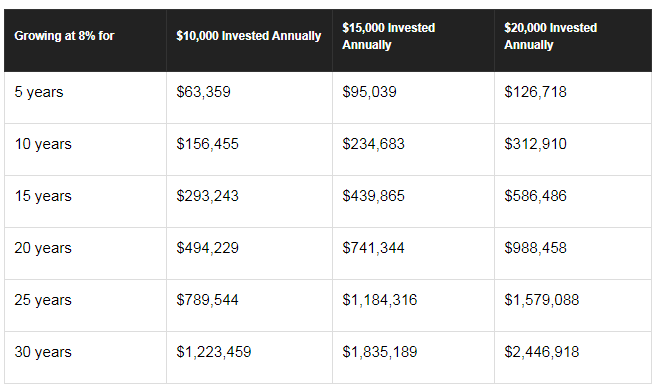

Clearly, investing for many years is an integral part of the formula that got these folks to millionairedom. Time is your best friend. If you can invest for a lot of years and can sock away sums considerably larger than $1,000, $3,000, or $5,000, you, too, can amass a hefty retirement account.

Here's what you'd end up with over various periods if your investments average 8% annual growth:

Are you ready to build your $100,000 (or bigger) portfolio?

Before you start calling a broker, take a few minutes to assess whether you're really ready to start investing.

- Are you saddled with high-interest rate debt, like credit card debt? If so, pay that off first.

- Do you have an emergency fund fully loaded, in case an unexpected big expense arises? If not, save enough of your income that could cover your living costs for six to nine months in a safe place before you start parking any money in the stock market.

- Are you mentally ready? Have you accepted that the value of your holdings will fluctuate, and sometimes you'll lose money in stocks? The stock market will occasionally stagnate or head south, and so will individual stocks. Don't sell in a panic.

- Are you willing to do a little math? It's good to be able to know what portion of your portfolio each holding represents and to notice as the proportions change. Your online brokerage should offer tools that can help you see your portfolio's composition and changes at a glance.

- Will you need any of the money you plan to invest in the stock market within five or 10 years? The stock market is only for long-term dollars, as you need to be able to ride out an extended economic downturn and not have to sell when prices fall.

- Can you tell the difference between a balance sheet and an income statement, and do you know where to find them? If you choose to invest in individual stocks, you'll need to make sense of their financial statements to see how healthy and promising they really are. If you opt for simple index funds, you can skip it.

- Do you know that it's much more important to understand and follow the company behind each stock than to obsess over daily stock prices? Buying stock makes you a part owner of actual businesses, and you should only invest in companies you understand.

- Do you have a long-term investment horizon, aiming to hold your stocks for years as long as they remain healthy and growing? It's tempting to chase a quick buck, but that's not how most big fortunes are built.

- Do you know how to compare your performance to a benchmark such as the S&P 500? If you're not beating these benchmarks over several years, rethink your strategy or opt for simple, low-fee index funds.

For long-term wealth building, look to the stock market

The stock market is the ultimate long-term wealth generator.

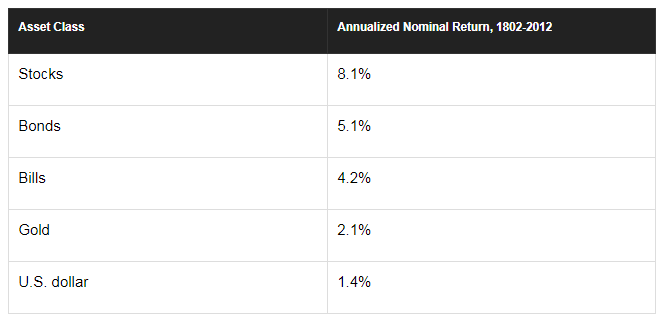

Stocks outperformed bonds in 96% of all 20-year holding periods between 1871 and 2012 and in 99% of all 30-year holding periods, according to Wharton Business School professor Jeremy Siegel. He calculated the average returns for stocks, bonds, bills, gold, and the dollar, from 1802 to 2012:

Want more recent numbers? The annualized growth rate for stocks from 1926 to 2012 was 9.6%, and that also easily beat the alternatives.

What's your investing style?

There are many different strategies to use in investing. A categorically bad method is to jump in and out of stocks frequently, not being patient enough for them to perform for you, and racking up trading costs. Another terrible strategy is buying lots of penny stocks -- stocks with shares trading for less than about $5 apiece -- as they tend to be easily manipulated, volatile and have cost countless investors loads of money.

Two more reasonable investment strategies are growth investing and value investing. Growth investors favor buying stock in fast-growing companies and they can be willing to pay a lot for them. They'll often ignore steep price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios, expecting stock values to keep rising as the companies grow. This approach can be risky, though, as the stocks or the overall market might pull back sharply.

Value investing, on the other hand, is a strategy where investors seek bargains, or stocks trading at prices significantly less than they are estimated to be worth. These investors focus on business fundamentals, such as cash flow, profit margins, and dividends. They also demand a margin of safety, which is what you get when you buy something for less than its intrinsic value. That margin of safety makes it likely that the asset will eventually appreciate, approaching its intrinsic value. Growth investors often forego a margin of safety, while value investors are more conservative. The ranks of value investors include the likes of Warren Buffett.

Make the most of retirement accounts

You can invest in stocks (and/or mutual funds) through regular, taxable accounts you open at a brokerage, but you can also use tax-advantaged retirement accounts such as IRAs and 401(k)s. It's smart to do so, since "tax-advantaged" means you'll probably save money -- potentially tens of thousands of dollars or more. You'll have to know the rules first, of course.

In 2019, you can contribute up to $6,000 to one or more traditional or Roth IRA(s) -- in total. If you're 50 or older, the limit is $7,000. With a traditional IRA, a $6,000 contribution will reduce your taxable income by $6,000. If you have taxable income of $70,000 and make a $6,000 contribution to a traditional IRA, your taxable income shrinks to $64,000 for the year, saving you a considerable sum in taxes. Money in an IRA can be invested and will grow on a tax-deferred basis, taxed only upon withdrawal, which will likely be in retirement, when your tax bracket may be lower.

With a Roth IRA, a $6,000 contribution has no effect on your taxes in the contribution year. Taxable income of $70,000 remains just that, despite a contribution to a Roth IRA. But follow the rules, and you'll be able to withdraw all your contributions and earnings tax-free! If your Roth IRA swells to $300,000 over 20 years, that can all be tax-free income in retirement.

Make the most of your 401(k) or 403(b) account, too. They sport much higher contribution limits than IRAs -- for 2019, the limit is $19,000, or $25,000 for those 50 or older. At a minimum, contribute enough to your 401(k) in order to grab all available matching dollars from your employer. That's free money, after all. A common match is 50% of your contributions, up to 6% of your salary -- meaning that if you earn, say, $80,000 per year and contribute $4,800 (6% of your salary) to your 401(k), your company would chip in an additional $2,400 in free money.

With all these option available to you -- regular brokerage account, IRA, 401(k), etc. -- it can be hard to know what to do. Here's one good approach: First, be sure you're contributing enough to your 401(k) to get all available matching funds. Then aim to fully fund an IRA -- because if it's held at a good brokerage, it's likely to feature low trading fees and will give you access to myriad stocks and funds. Beyond that, you can allocate more money to your 401(k) and/or your regular brokerage account, depending on how you want your dollars invested. (A 401(k) will likely offer a limited menu of investment choices -- if a low-fee index fund is among them, that can be all you need.)

Open a brokerage account

Once you're ready to invest, you'll likely need a brokerage account. (We'll soon get to what, exactly, you may want to invest in.) Through a brokerage, you can open one or more IRA accounts as well as regular, non-tax-advantaged investment accounts. In any of those accounts, you'll be able to trade stocks -- and you can very likely buy and sell bonds and mutual funds, too.

Most major brokerages let you open an account online, over the phone, and/or in person. Once you have an account, you can fund it with money and then proceed to place orders for stocks and other securities.

Be aware that there are different kinds of brokerages, and one key distinction is the full-service brokerage vs. the discount brokerage.

Full-service brokerages are more old-fashioned, and aim to do much of the investing work for you -- recommending various investments and often managing your money for you. In exchange for this, they charge heftier fees -- such as several hundred dollars per trade -- and not all of their recommendations will serve you well.

Choosing a brokerage account for your portfolio

Fortunately, there are plenty of good brokerages to choose from, many of which charge low trading commissions -- $7 or less per trade -- and offer research and access to financial advisors, too.

When you're ready to open an account, choose your brokerage firm carefully, selecting one that best suits your needs. Below are some considerations you might keep in mind:

- Minimum initial deposit: Some brokerages require at least several thousand dollars, while others have no minimum.

- Fees: All other things being equal, favor brokerages that charge little per trade, keeping in mind you'll pay more in fees if you trade frequently. Consider other fees, too, such as IRA custodian fees, wire transfer fees, account inactivity fees, and annual fees.

- Research: Many brokerages offer free company research reports and tools such as stock screeners.

- Mutual funds: The range of funds offered by brokerages varies, with some brokerages offering a handful of funds and others offering thousands. If you're interested in particular funds, see whether they're available. You can also buy into funds directly from the issuing companies, bypassing brokerages.

- Non-stock offerings: If you're interested in investing in bonds or other non-stock securities, see whether they're offered.

- Usability: Look into how easy to use each brokerage's online trading system seems to be and how user-friendly its website is.

- Customer service: Ask some questions of the customer service department to see the responsiveness.

- Banking: Some brokerages feature banking services, such as check-writing, money market accounts, credit cards, ATM cards and direct deposit. Look for these if you want them.

- Convenience: Would you rather place trade orders through an actual person, your phone, or online? See which brokerages offer what you prefer. Some have brick-and-mortar locations, for instance, while others are only available online.

Some of these factors will be more important to some investors than others. Make a list of the features you need or want -- then evaluate each contender on all the measures.

These investments will help you build a $100,000 (or greater) portfolio

Once you're ready to invest -- because you're free from high-interest debt, have a robust emergency fund, and have opened a retirement and/or brokerage account -- your next task is selecting your investments. Consider these options:

1. Index funds

The best way for most people to invest in the stock market is through a low-fee, broad-market index fund, such as one based on the S&P 500, that delivers roughly the same returns of the overall stock market. After all, few of us have the time, energy, skills, or interest to become a hands-on investor, carefully studying companies and deciding when to buy and sell various stocks. That's OK, because you can do as well -- or better -- by investing in index funds.

Index funds, which are considered passive investments, actually outperform most actively managed mutual funds -- where well-paid professionals use their judgment to choose which stocks and other securities to buy and sell. For example, over the 15 years ending in June 2018, about 92% of U.S. large-cap stock mutual funds lagged the returns of the S&P 500. It's the same with indexes of smaller companies. About 95% of U.S. mid-cap stock funds trailed the popular S&P MidCap 400 index over those 15 years, while the S&P SmallCap 600 index outperformed nearly 98% of all U.S. small-cap funds.

Each index fund tracks a particular index, giving your portfolio the approximate return of the index -- less fees, which can be kept quite low with certain funds:

- The Vanguard 500 Index Fund (NASDAQMUTFUND:VFINX) tracks the S&P 500 index, which is made up of 500 of America's biggest companies that together represent about 80% of the entire U.S. stock market's value.

- Even broader, the Vanguard Total Stock Market Fund (NASDAQMUTFUND:VTSMX)encompasses all of the U.S. stock market, including small companies.

- The Vanguard Total World Stock Index Fund (NASDAQMUTFUND:VTWSX) parks your money in the total world stock market.

Plenty of other brokerages or fund families beyond Vanguard offer low-cost index funds, too -- very possibly including some available to you via your brokerage or workplace. (We use Vanguard as the benchmark because it's the low-cost index-fund pioneer.)

You can also opt for exchange-traded funds, or ETFs, that focus on the same indexes -- such as:

- The SPDR S&P 500 ETF (NYSEMKT:SPY)

- The Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF (NYSEMKT:VTI)

- The Vanguard Total World Stock ETF (NYSEMKT:VT)

If you want to include some bonds in your portfolio for diversification, you can do so via index mutual funds and ETFs as well. The Vanguard Total Bond Market ETF (NASDAQ:BND) is one possibility.

Choose index funds with ultra-low fees, because there are plenty, and there's no need to pay more than you have to just to mimic the market's performance. The higher your fees, the lower your return -- and the slower your money will grow. A typical managed stock mutual fund might carry an annual fee ("expense ratio") of 1% or 1.5% or more, while many broad-market index funds sport annual fees of less than 0.25% or even 0.10%.

Index fund investing is easy and cheap, and delivers returns that beat many more expensive alternatives. Plunk your money regularly into index funds and, voila, you're done. It's a perfect kind of investing for most of us.

2. Managed mutual funds

Managed mutual funds, as noted earlier, generally won't grow your money faster than lower-fee index funds will. There are rare funds that will beat the market on average, but it can be hard to find them.

Most managed funds have particular focuses. Some invest solely in stocks, others in bonds, and some in a variety of asset types. Stock-centered ones are often referred to as "equity" funds, and they can focus on small, medium-size, and/or large companies (often referred to as "small-cap," "mid-cap," and "large-cap" companies). Some seek regular income through dividend-paying companies. Others focus on interest-paying securities (such as T-bills, bonds, and notes) and are referred to as "fixed-income" funds. "Balanced" funds will typically feature both stocks and bonds. Funds focused on real estate investment trusts (REITs) will hold shares in various real estate companies and will often pay meaningful dividends.

Meanwhile, "growth" mutual funds focus on stock in fast-growing companies, while "value" funds look for undervalued gems. Some mutual funds specialize in one industry or niche (such as financial services, energy, utilities, or healthcare) and others in a region (such as China, emerging markets, Europe, Asia, or Latin America).

Mutual funds also vary in complexity and risk. Some funds look for stocks that the managers think will fall, and then take huge bets against them -- "shorting" them. Others use leverage (borrowed money) aggressively, aiming to turbocharge returns while also turbocharging risk. Closely examine any fund candidate to see how it would invest your money.

3. Individual stocks

Investing in individual stocks is another option, as you aim to get your portfolio's value to $100,000 or more. This strategy will require you to be rather savvy and informed about investing in general and about the businesses you're investing in. For example, before investing in any company, you should:

- Know its major products, services and competitors.

- Be able to explain exactly why you're buying it and what would make you sell it or change your reason for owning it.

- Understand its competitive advantages.

- Be familiar with the risks it faces and why it may not prosper.

- Study its financial statements and assess various measures such as profit margins and growth rates.

- Have multiple sources of information about it, with a diversity of perspectives.

- Expect to keep up with it, tracking its performance and reading its quarterly reports.

This checklist may intimidate you into sticking with simple index funds, and that's perfectly reasonable. You may very well do better with index funds than with individual stocks -- most people do. But if you do manage to invest in stocks that turn out to be long-term outperformers, you can do incredibly well. (Remember that you could also opt to have most of your money in index funds, investing in individual stocks with only a small portion of your portfolio.)

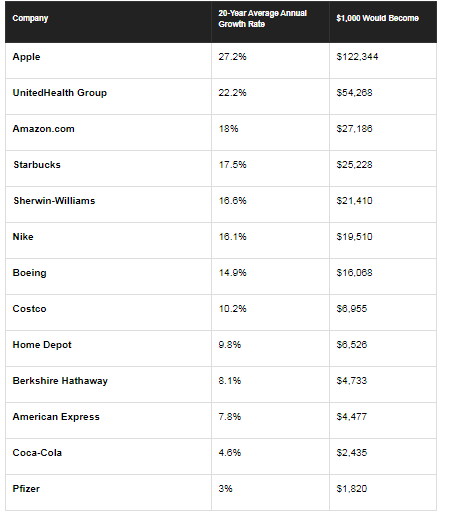

Here are the 20-year returns of familiar stocks to give you an idea of the range of returns possible for an investor, keeping in mind the plethora of companies that have fallen in value or gone out of business. It's not just high-tech companies delivering huge returns -- even sneaker companies and airplane makers and coffee vendors can generate enormous wealth for smart-minded investors.

For context, the S&P 500 averaged annual growth of about 5.6% for the same period, which is lower than its long-term average of closer to 10%. This is a good reminder that over the many years you'll be invested in the stock market, you can expect returns significantly above or below average.

4. Dividend-paying stocks

It's also smart to include dividend-paying stocks in your portfolio, for a variety of reasons.

For one thing, as long as the companies are healthy, they'll likely keep paying dividends even during market downturns -- and that money can be reinvested in more stock. You can do the reinvestment on your own, by letting dividend dollars accumulate in your account until you use them to buy more stock -- and some brokerages will automatically reinvest dividends for you.

Long-term average annual gains for dividend-paying stocks tend to be significantly higher when dividends have been reinvested. For example, over the past 20 years, Boeing stock has averaged annual growth of 13.1% without dividend reinvestment and 14.9% with dividends reinvested in additional shares of Boeing stock. Dividend-paying companies tend to be more stable than their counterparts as well.

If you build a portfolio of strong dividend payers, you can expect them to deliver a welcome income stream in retirement. If you invest $400,000 in dividend payers with an average dividend yield of 3%, you're looking at $12,000 in annual income -- and dividends tend to be increased over time, too.

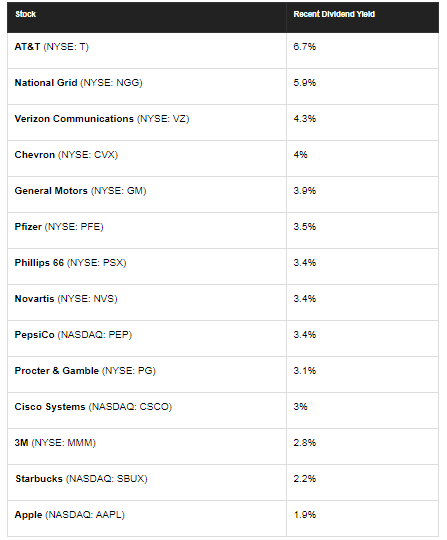

The table below shows some dividend payers and their recent dividend yields. A dividend yield is a company's annual dividend amount divided by its recent stock price. So a company paying $1 quarterly will have a $4 annual dividend, and if its stock price is $100, its dividend yield will be 4% -- 4 divided by 100.

You can absolutely build a $100,000 portfolio -- and even a million-dollar one -- if you save aggressively and have a long time horizon.

It doesn't have to be complicated, either: Open a brokerage account and regularly invest money you don't need in the near term in a low-fee, broad-market index fund. And if you want to become the next great stock picker, start reading and learning a lot about business and investing. Fool.com is a great place to start.

This article originally appeared in the Motley Fool

John Mackey, CEO of Whole Foods Market, an Amazon subsidiary, is a member of The Motley Fool's board of directors. Selena Maranjian owns shares of Amazon, American Express, Apple, Berkshire Hathaway (B shares), Boeing, Costco Wholesale, National Grid, Novartis, Procter & Gamble, Starbucks, and Verizon Communications. The Motley Fool owns shares of and recommends Amazon, Apple, Berkshire Hathaway (B shares), and Starbucks. The Motley Fool has the following options: long January 2020 $150 calls on Apple, short January 2020 $155 calls on Apple, short February 2019 $185 calls on Home Depot, and long January 2020 $110 calls on Home Depot. The Motley Fool recommends 3M, Costco Wholesale, Home Depot, National Grid, Nike, Sherwin-Williams, UnitedHealth Group, and Verizon Communications. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.