How Caring For A Dementia Patient Can Take Its Own Mental Toll

This article originally appeared on Kaiser Health News.

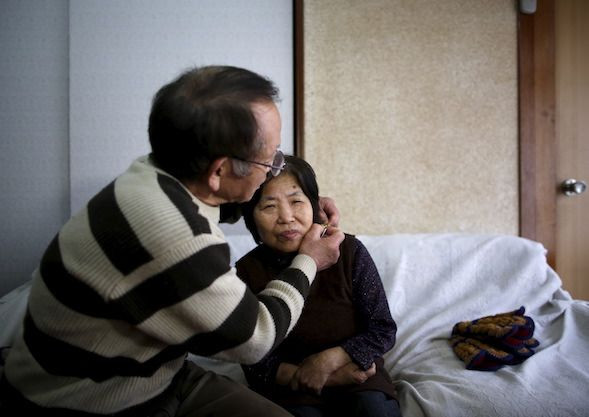

Michael Sloss’ mother was diagnosed with dementia about five years ago, and his father a year after that.

Now Sloss and his brother care for both parents, ages 83 and 85, whose personalities have been transformed by the decline in their mental and physical health.

The brothers wrestle with their parents’ memory loss, anger and delusions. They nurse them when they’re sick and help them bathe. And they lift their father into and out of bed.

“Mostly, it’s been rough,” says Sloss, 60, of South Pasadena, Calif. “But we have been blessed with a lot of support.”

The brothers first sought help from their family’s church, which offered a respite when their parents attended Bible study and fellowship for a few years after their diagnoses. But that ended when the elder couple’s physical ailments made it too difficult to transport them to and from services.

Eventually, the brothers found the USC Family Caregiver Support Center, which has connected them with support groups, caregiver classes and services that give them breaks from caregiving.

The USC organization is one of 11 nonprofit Caregiver Resource Centers across California that serve about 14,000 families a year. Their aim is to offer low-cost or free services, regardless of income, to people caring for someone 18 or older.

Their offerings include stress-busting activities like yoga and meditation; legal and financial consultations; and tips on how to choose a home health agency, talk to doctors or manage difficult behavior.

“This was designed to help everyone, including middle-income families,” says Donna Benton, director of the USC center.

A 2015 report by the AARP Public Policy Institute and the National Alliance for Caregiving found that roughly 43.5 million adults in the United States had provided unpaid care to an adult or child in the prior year.

The need is expected to increase as baby boomers age and become caregivers for loved ones or require care for themselves, says Amy Goyer, AARP’s family and caregiving expert.

“As our health care improves, people live longer, but they tend to live longer with chronic illnesses or conditions,” she says.

There also will be a declining number of caregivers for those in need, because Americans are having fewer children and family structures are changing, Goyer adds.

Simply put, caregiving is hard, it may get harder, and it often leads to emotional, physical and financial hardship.

“People tend to think it’s something temporary … like a sprint, and then it turns into a marathon,” Benton says. “And then you have all the wrong coping tools. Then you burn out.”

Goyer cares for her father, who is 93 and has Alzheimer’s disease. Caring for a loved one with Alzheimer’s or dementia adds an extra burden because of its intensity, she says. “It’s caregiving on steroids because of the constancy of it.”

Help is available, much of it for free. But the network of resources is like a “puzzle you put together,” Goyer says, so be prepared to make multiple calls and queries to different organizations.

If you’re in California, start with the Caregiver Resource Centers. Find out which one serves your county through the Family Caregiver Alliance or calling the USC center at 800-540-4442 to be transferred to the right location.

A staff member will work directly with you to determine what you need.

“We’re there as a comprehensive, one-stop center,” Benton says. “If you have someone who helps you cut through the red tape, it can save you hours and days of aggravation.”

Whether or not you’re in California, Goyer suggests, reach out to your local Area Agency on Aging, which can also connect you with resources. Visit eldercare.gov and enter your ZIP code to find local contact information.

When you call, request a personalized assessment of your situation, Goyer recommends.

“Always ask them, ‘What support do you have for caregivers?’ The person you’re caring for might be eligible for chore services or housekeeping or respite care,” which can give you a break from caregiving, she says. “In some cases, if their income qualifies them for Medicaid, they might be able to get home health aides.”

The Family Caregiver Alliance, a national group based in San Francisco, can link you to support, most of it free. Visit www.caregiver.org and click on the “FCA CareJourney” tab to fill out the online survey.

After you receive personalized suggestions, you can follow up with a staff member online or by phone (800-445-8106), says Executive Director Kathleen Kelly.

The alliance, which has been helping caregivers for nearly 40 years, says its clients frequently ask how they can better care for their loved ones, where they can find emotional support for themselves and whether they can get paid for the care they are already providing, since many of them had to quit their jobs, Kelly says.

Their needs change over time. “We’re a place that people can come back to,” she says. “We deal with people over the long term.”

If you’re interested in doing more digging:

Visit aarp.org/caregiving, where you can find help in multiple languages, free online webinars and resource guides. Contact disease-specific organizations such as the Alzheimer’s Association or the American Cancer Society; or Leeza’s Care Connection, which offers resources and information for caregivers. Reach out to friends, family members, neighbors and your place of worship, if you have one. Hospitals often have social workers who can help connect you to services.

Sloss, the South Pasadena resident, has taken classes that have taught him to better communicate with his parents and defuse confrontational behavior. He and his brother have also benefited from respite care, which allows them to have some time for themselves. And they have relied on their caregiver group for emotional support.

“Those are people going through the same things you’re going through and can really identify with your situations,” Sloss says. He urges other caregivers not to forget about their own health and happiness.

“Seek help. You should definitely get a respite, whether it’s from a family member, friend or organization, because you need time to recharge,” Sloss says.

“Unfortunately, some of the patients outlive the caregivers because the caregivers don’t necessarily take care of themselves.”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.