How Human Breast Milk Became A Hot (And Controversial) Commodity In The United States

Allison had never met the woman who rang her doorbell one wet, bone-chilling Saturday morning in October. But after Allison welcomed Liz Lipman-Stern into her cozy New York City apartment, the two mothers faced each other for only a few seconds before embracing.

“Thank you,” Lipman-Stern murmured, her voice heavy with gratitude.

Allison pulled away and strode to a waist-high deep freezer in a corner of her living room. She withdrew two clear gallon-size bags, each containing smaller frozen pouches of a creamy, pale yellow liquid — Allison’s breast milk. Lipman-Stern took them gingerly and knelt to pack them into two coolers she’d brought as she and Allison exchanged tales of diaper rash. When the milk was secure, Lipman-Stern headed back out into the rain.

The two mothers had met on Facebook weeks earlier through a milk-sharing group. Lipman-Stern, an older mother, couldn’t produce the milk she wanted her daughter, Julia, born through a surrogate, to drink for at least a year. Allison, 29, who did not want her full name used because of privacy concerns, had begun pumping milk about six weeks after giving birth to her son, and quickly realized she made more than he could drink. After some Googling, she decided to donate her milk for free to a baby in need.

The sharing of human milk has skyrocketed in recent years throughout the United States. Driven by a blend of altruism, practicality and pure maternal instinct, some mothers sell their milk by the ounce to for-profit milk banks or to buyers found online. Others eschew compensation and donate to nonprofit milk banks or directly to parents, often finding them through social media, particularly the Facebook groups Eats on Feets and Human Milk 4 Human Babies. This flourishing sector is largely free from formal oversight. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration treats human milk as a food, rather than as a tissue or a medicine, and it advises against but does not regulate informal sharing networks like the Facebook group Lipman-Stern and Allison used.

Many parents welcome the freedom to give or receive breast milk at their prerogative. But others who study or are a part of the burgeoning human milk industry fear that this free-for-all is more dangerous than empowering and that without stricter oversight, babies could drink milk containing harmful viruses, bacteria or adulterants. Milk sharing also appears to take place mainly among middle- or upper-income educated white women, raising concerns about low-income mothers’ access to human milk. As milk sharing gains popularity and visibility, mothers, fathers, academics, legislators and businesspeople across the U.S. have found themselves grappling with fraught questions about the safest, most ethical and most efficient ways for human milk to change hands.

“Everyone is trying to figure out where society should be going on these issues,” said Sarah Keim, a principal investigator at the Center for Biobehavioral Health at the Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. “There’s definitely no consensus.”

In the last four years, the practice of selling, buying or giving milk to people found online has quadrupled, research by Keim suggests. In 2011, more than 13,000 women posted on websites offering or asking for milk. By 2015, that number had risen to more than 55,000.

Sweeping endorsements of breast milk by policymakers and medical groups have been key in spurring this growing interest. In 2011, the U.S. surgeon general issued a national call to support breast-feeding. The following year, the American Academy of Pediatrics released a policy statement saying that babies should be exclusively breast-fed for at least their first six months of life. It added that if premature babies weighing less than 1,500 grams, or 3.3 pounds, could not get milk from their mothers, they should receive donor milk from a bank affiliated with the Human Milk Banking Association of North America, which oversees nearly two dozen nonprofit milk banks that collect and pasteurize breast milk donated by prescreened mothers, then sell it to hospitals.

The shift in breast-feeding attitudes and practices is gradual but discernible. In 2007, 11.3 percent of babies in the U.S. were breast-fed at six months. By 2014, the proportion had risen to 18.8 percent. Popular perceptions about milk versus formula changed, too. In a national survey by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2007, 20.2 percent of respondents said infant formula was as good as breast milk. By 2014, 15.5 percent said so. Meanwhile, the amount of milk distributed to hospitals by the Human Milk Banking Association of North America rises 20 to 25 percent every year.

Millennia of Milk Sharing

In April 2015, four weeks before her due date, Rachel Sardina, 30, gave birth to her daughter, Teresa. Sardina tried to nurse her right away, but Teresa was a small baby, with a tiny mouth and a lip tie that shot pain through Sardina’s nipple every time Teresa tried to wrap her mouth around it.

“It wasn’t how I envisioned it going,” Sardina said. “Everything I read was like, ‘Breast-feeding is so natural; babies automatically know what to do, and you know what to do,’ ” she said.

For Teresa’s sake and her own, Sardina decided to exclusively pump. From day one, she produced far more than Teresa could drink. In October, her daughter drank an average of 24 to 28 ounces of milk daily; Sardina produced 45. The extra milk rapidly filled the tiny freezer in her cozy apartment in Queens, New York.

“I would never want to waste it,” Sardina said. “I think all children should receive breast milk.”

The group Human Milk 4 Human Babies had come up in breast-feeding support groups Sardina belonged to on Facebook, so she contacted some of the mothers who had posted asking for milk. One of them was Lipman-Stern, and Sardina offered to regularly hand over her extra milk for free.

The idea of a woman giving milk to a baby who is not hers is an ancient one. Wet nursing — one woman breast-feeding another woman’s child — dates as far back as 2000 B.C. in Egypt and Israel. During the late Roman Empire, wet nurses, who were often slaves, were contracted to feed babies that had been abandoned, and in some European countries during the Renaissance, wet nursing was a strictly regulated paying job. In some circumstances, hiring a wet nurse was a choice, such as for high-society mothers who did not want to ruin their figures. In other instances, the practice was necessary, because nursing can go awry for myriad reasons.

Research suggests that babies who drink breast milk reap a host of benefits, from reduced risk of childhood leukemia to fewer stomach problems. Breast-feeding also has perks for mothers, lowering their risk of ovarian and breast cancer.

But premature babies can’t always latch on to a human nipple, and even children born after a normal gestation period can have conformation issues — a cleft palate or lip, or an upper lip tie — that prevent them from nursing successfully. Problems can come from the mother’s side, too. She might not produce enough milk, and if she doesn’t begin to breast-feed or pump shortly after giving birth, her supply will dry up, making it difficult if not outright impossible to produce milk later on. Parents who adopt and the rising number of those who have children through surrogates also cannot nurse their children.

Even successful nursing can be rife with technical difficulties, and it requires sticking to a grueling schedule. “Breastfeed at least 8 to 12 times every 24 hours to make plenty of milk,” a guide by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends. “This means that in the first few days after birth, your baby will likely need to breastfeed about every hour or two in the daytime and a couple of times at night.” Breast-feeding mothers may also contend with sore nipples, leaks, plugged ducts, infections or “strikes,” where babies refuse to nurse.

“The assumption is that breast-feeding is natural and it’s easy to do,” said Pauline Sakamoto, president of the Human Milk Banking Association of North America. In reality, she said, “it’s a learned biological dance between the mother and child.”

The other major reason milk sharing has taken off is indisputably the proliferation of the human breast pump. Under the Affordable Care Act, the landmark healthcare law passed in 2010, insurers are required to cover the cost of the device. As new mothers return to work, having a pump allows them to express milk even when their babies are not by their sides. And the more mothers pump, the more likely they are to have excess milk, which many are loath to throw out, not only given the effort it takes to produce it but also as awareness grows about the benefits of breast milk.

“The pump is a major driver in all of this,” Keim said.

Needing a Stranger’s Milk

Shelley Duchemin knew something was wrong when she found yellow dust instead of urine in her son’s diaper three days after he was born in June 2011. Duchemin had been nursing him at her breast, but even then he cried and fussed. The dust, the doctor said, meant that her son wasn’t actually drinking anything when he nursed, because no milk was coming out.

“He was starving to death,” Duchemin, a stay-at-home mom who is now 36, said. The cause turned out to be a combination of a medication she had been taking and the removal of a tumor from her pituitary gland.

Duchemin, who had breast-fed her first child, a daughter, began feeding her son organic baby formula, but he threw up constantly. Four months later, a note that a friend posted online reminded her that she could find donor milk through Facebook sites like Eats on Feets and Human Milk 4 Human Babies. She began using them to find donated milk for her son, and continued doing so after she had her second daughter about a year later, because she still couldn’t produce enough milk of her own. For three years straight, Duchemin and her husband drove all over their home state of North Carolina — and sometimes beyond, as far away as Massachusetts, if they were already traveling in that direction — to get milk for their children.

As many as 60 other mothers donated to her family, Duchemin estimated. Some of them were friends, while she found others through Facebook. Although she specifically requested milk from mothers who did not smoke or take mood-altering medications like antidepressants, Duchemin was generally trusting.

“All the ladies that were donating were using their own milk for their own babies,” she said. “Since they weren’t selling it, they had no reason to water it down or anything like that.”

Before accepting milk, Duchemin often met with donors, who would volunteer information or readily answer questions about smoking, drinking or medications. She was never afraid that her children would be harmed by the milk, because “the people I met, they went out of their way to prove that they were OK,” she said.

Lipman-Stern also judged donating mothers with a heavy dose of faith in the ethos behind milk donations — the sentiments, or perhaps principles, of generosity, female empowerment and altruism. When she asked donors to fill out a detailed 30-odd question survey about their daily habits and medical history — “Have you ever tested positive for: TB, HTLV I or II, HIV I or II, Herpes Simplex, Hepatitis B or C, or Syphilis?” or “Do you dye your hair? What product do you use and how often?” or “How do you clean your milk collection items?” — she trusted that they were telling the truth. Once, she rejected milk from a mother who was on birth control, fearing the hormones would be passed to Julia.

A study of 867 milk donors and recipients published in December in the journal Maternal & Child Nutrition found that more than 90 percent of milk recipients screened prospective donors. The concerns varied from parent to parent. Some cared more about the donating mother’s diet. Did she drink caffeine or alcohol, or take medications? Others focused on medical history or prioritized the age of the donor’s baby when the milk was pumped, so that it would align with their own baby’s age.

“Screening processes are really situational and subjective,” said Aunchalee Palmquist, a medical anthropologist at Elon University in North Carolina who co-authored the study. “That’s what makes it such a complex public health issue.”

Not all recipients screen donors, several mothers who donated milk said. When Sabrina Abraham, a 30-year-old mother in Ottawa, Ontario, gave away about 50 ounces of her milk in June to a woman she met on Human Milk 4 Human Babies, the older woman who came by her house hardly questioned her. “She didn’t ask me about my health,” Abraham said. “I was ready to tell her, ‘I don’t drink alcohol or smoke. I drink a cup of coffee a day.’ ”

When Leah Labrecque, a children’s librarian in Brooklyn, New York, with a 7-month-old daughter, gave away a few dozen ounces in September to a local mother she met through Facebook, Labrecque simply told the mother that she drank “a little bit” and didn’t smoke, take medications or have any diseases. “She didn’t really ask anything more than what I’d supplied,” Labrecque, who has also donated milk to friends and to her sister-in-law, said.

The FDA has no codes, laws or regulations governing breast milk exchanges, although it does offer guidelines. “If, after consultation with a healthcare provider, you decide to feed a baby with human milk from a source other than the baby’s mother, you should only use milk from a source that has screened its milk donors and taken other precautions to increase the safety of the milk,” Lauren Kotwicki, a spokeswoman for the FDA, said.

The theory among proponents of milk sharing is that when money does not change hands, milk is far less likely to be contaminated. It’s one reason accepting free milk from another mother feels safe to many parents. Keim, however, suggested that such logic was idealistic but flawed.

“Free milk has got to be safer, right? I don’t think we know that yet,” Keim said. “We know that not everyone is truthful about their health behavior.” FDA regulations would be welcome, she said, but “it’s difficult to figure out how they would be enforced.”

But activist Emma Kwasnica, who founded Human Milk 4 Human Babies, said that since launching the network in 2010, “I have heard of not one baby coming down ill or become sick from donor milk through peer-to-peer sharing.” Explaining that volunteers who manage the site’s pages, along with milk donors and recipients, are in touch with her constantly, she added, “If anyone would know, it would be me.”

Ingredients: Human Milk?

The more that parents look to strangers for their babies’ milk, the more experts worry that babies could acquire diseases, become ill or even die from drinking tainted shared milk, even though that does not appear to have happened so far.

Breast milk can occasionally “transmit serious viral and bacterial diseases” to newborn children, noted a 2009 study conducted by researchers at a hospital in Ireland and published in the journal Clinical Microbiology and Infection. They highlighted the case of an immune-weakened premature baby who died from an infection of the bloodstream, “likely to have been caused by contaminated breast milk” from the baby’s own mother. Similar cases of babies sickened by bacteria suspected to have been transmitted through their own mother’s milk have been documented but remain rare.

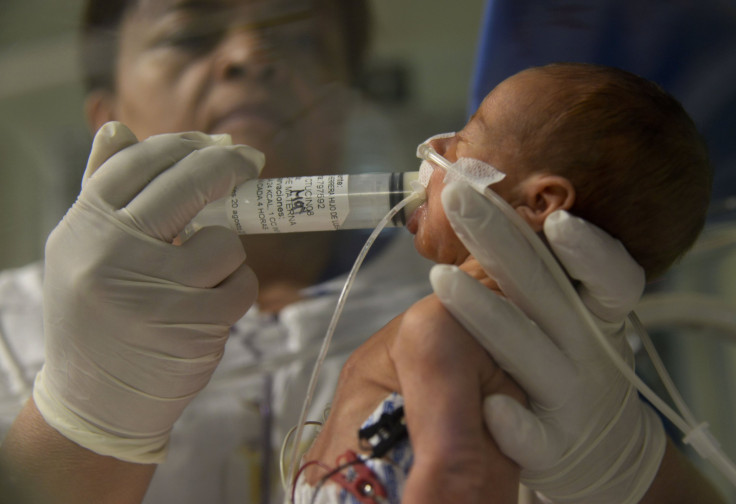

So far, donor milk from nonprofit banks, which sell screened and pasteurized milk to hospitals for infants in neonatal intensive care units, appears safe. “There is no documented case of a baby being harmed with donor milk from a HMBANA milk bank,” said Naomi Bar-Yam, president-elect of the Human Milk Banking Association of North America.

A search of FDA enforcement reports for recalled donor breast milk turns up two recalls. One, in 2013, was initiated by a nonprofit bank after a donor tested positive for hepatitis B. Bar-Yam said that after the recall, the babies who had drunk the milk were monitored, and “none of them were harmed.” The other recall, of 63 bottles in 2015, was due to the discovery of a plastic fragment in one bottle.

If certain risks are inherent in drinking human milk, then those threats are likely enhanced when milk is bought or sold and producers are motivated by the chance to turn a profit, and especially when those sellers are overseeing themselves, experts said.

Keim, the Nationwide Children’s Hospital researcher, has extensively researched and tested milk bought online. One study, published in 2013 in the journal Pediatrics, found samples of milk to be contaminated with bacteria that could be dangerous for some infants, although every baby reacts differently to certain substances, Keim pointed out. Another study, published in April, also in Pediatrics, found that 10 out of 102 samples of human milk bought online contained enough cow’s milk for Keim and her co-researchers to conclude that it had been added deliberately.

Last fall, Keim and several other researchers also published findings from when they tested milk bought online from sellers who advertised themselves as healthy — think of a nonsmoker who exercises regularly and eats well. “Out of 100 samples, four had high enough levels that we were confident that those women were smokers,” Keim said.

Those findings applied specifically to milk bought online, not milk given away for free, or from nonprofit milk banks, which constitute a major source of human milk for hospitals in the U.S.

The Milk Shortage

Since the 1980s, hospitals that need donor milk for infants, generally premature ones in neonatal intensive care units, have bought it from nonprofit milk banks, which don’t pay donating mothers. Although this sector launched decades ago, nonprofit banks still do not provide enough milk for hospitals. Nor are the safety regulations regarding them uniform, or even clear-cut, creating an open space for other players to enter the world of milk banking.

Every year, the two dozen banks that are part of the Human Milk Banking Association of North America distribute roughly 3.7 million ounces of human milk to infants in hospitals. But one estimate in 2007 found that if all preterm infants in hospitals across North America drank donor milk, rather than some of them receiving formula, hospitals would need about 8.9 million ounces annually.

This summer, the nonprofit milk bank that supplies the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia could not provide all the milk the hospital had ordered — typically about 600 ounces a week, said Diane Spatz, the head of the hospital’s lactation program.

“We had to decide — and this is really hard as a clinician — which baby is healthier to take off the donor milk,” she said. “I think that the shortage is real.”

Meanwhile, the legal landscape for milk banking in the U.S. is the “wild, wild West,” said Sakamoto, the president of the Human Milk Banking Association of North America, which issues its own voluntary guidelines for collecting, processing and distributing milk.

The FDA treats human milk as a food, while California, New York and Maryland treat human milk as a tissue. Milk banks in those states have to meet state standards for inspections, testing and screening, the same way a blood bank would.

Other states are exploring different approaches. In 2015, lawmakers in New Jersey and Michigan proposed laws to govern human milk banking. The bill in Michigan would differentiate between for-profit and nonprofit milk banks, subjecting the latter to more stringent oversight and requirements, while the New Jersey proposal would require all milk banks to be licensed and inspected by the state.

Amid this piecemeal regulation, sharing human milk is rapidly expanding beyond the realm of free mother-to-parent exchanges and nonprofit milk banks and into the world of selling, for a profit, a product that has become known as liquid gold.

The Hottest New Commodity

In October, Shannon Clearwater, 31, left her first shipment of frozen breast milk on the front steps of her house in Cornwall-on-Hudson, New York, and went to work. FedEx picked up the box that day and hauled it off to Tiny Treasures, a milk bank operated by Prolacta BioScience, a for-profit company. Her daughter, born in May, had struggled to put her tongue in the right place for nursing, choking on the flow of milk instead of drinking it. So Clearwater decided to pump instead. She was soon producing around 90 ounces of milk a day — triple what her daughter drank.

“I feel like it’s a good thing to share breast milk, but at the same time, there’s debts to pay back — student loans, daycare,” said Clearwater, who has also donated about 3,200 ounces of her milk to a local mother, whom she found through Eats on Feets. “Right now I really need a new roof,” she added.

After going through a screening process that involved sharing her medical history, getting approval from both her physician and her daughter’s pediatrician, measuring the temperature of her freezer, completing a blood test and submitting a DNA cheek swab, Clearwater was approved to sell her milk to Tiny Treasures. She said that so far she has sold about 4,500 ounces, at $1 an ounce.

In the U.S., two for-profit companies, one of which is Prolacta, currently offer to pay prescreened women for milk, which is then tested, processed and sold to hospitals. These companies’ processes for treating and testing milk remain opaque and under wraps, doctors and researchers said.

With a paid system, more women would be willing to produce more milk and part with it, thus reducing the shortage of milk, argue advocates of the paid model. For-profit companies claim to break new ground in other ways, with more stringent screening, more advanced processing, safer milk and income for mothers, to top it all off.

Prolacta was founded in 1999 and began selling a human milk fortifier to hospitals in 2006. The other company, Medolac, was founded in 2009. It says it makes sterile, shelf-stable milk that it sells to hospitals. Medolac, which partners with Mother’s Milk Cooperative, an Oregon-based milk bank that pays mothers $1 per ounce, also sells milk directly to parents, as long as they provide a note from their baby’s doctor, the company says.

Prolacta’s fortifier, which is added to breast milk that is then fed to premature babies in hospitals, has been shown to reduce the risk of those infants’ developing a dangerous condition called necrotizing enterocolitis, where part of the intestine dies, compared to those fed with dairy-derived fortifiers.

In the process used by nonprofit milk banks, known as Holder pasteurization, milk is heated to 144.5 degrees Fahrenheit (62.5 degrees Celsius) for 30 minutes in order to kill harmful bacteria. Sterilizing milk, the process Medolac says it uses, destroys all germs. But the process has also been found to denature certain proteins and decrease vitamin content, at least with cow’s milk.

Still, Medolac’s website promises, “The company specializes in innovative, human donor milk products for clinical use, applying proprietary biopharmaceutical processing methods that preserve many of the immune components in human milk.”

And Doug Hawkins, vice president of Medolac, insisted that MedoLac offers something unique. “We bring products that are not just the status quo,” he said. “The commercially sterile human donor milk that’s shelf stable for three years — no one else has ever done that.”

Outside the medical world, anyone can buy or sell milk through the website Only the Breast, which was founded in 2009 and has been nicknamed — and not always flatteringly — the Craigslist of breast milk. Mothers can post listings to the site to sell milk at a price they decide on and to whomever they choose, even men.

Glenn Snow, founder of Only the Breast, is in the process of launching a company called International Milk Bank that he said would pay women for their milk and whose products would compete with those of Prolacta and Medolac. He claimed to have also developed an unprecedented sterilization method that would make human milk uniquely safe and healthy but refused to share details about what he said were “proprietary methods.”

“The production of milk is not free,” he said. Donating mothers are “in the luxurious position of being able to give it away,” but not every woman can enjoy that luxury, he said.

An Imperfect Model

The for-profit milk industry may appear to be expanding rapidly, with at least one website connecting buyers and sellers and two young companies that pay mothers for milk, with another on the way. But it also rests on several assumptions that doctors and mothers alike see as fundamentally flawed.

Dr. Richard Schanler, the director of neonatal services at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New Hyde Park, New York, questioned Medolac’s claims about quality and safety. He was skeptical that sterilized milk was actually more nutritious for babies. There was “no data to say that theirs is better than anybody else’s,” Schanler said of Medolac’s product.

Whether hospitals can afford the for-profit companies’ products is another issue. Milk from nonprofit banks already costs from $4 to $5 dollars per ounce, which the Human Milk Banking Association of North America says barely covers the cost of testing, pasteurization and other processing. Medolac claims its prices are comparable to those of the nonprofit banks, but Prolacta’s human milk-derived fortifier ranges from $125 to $312 per bottle, while its pasteurized milk costs $14 an ounce.

“We’d love to use Prolacta, but that’s very expensive,” Schanler said. The hospital has used Prolacta products previously but cut back because of the high cost, and for now, its weekly shipments of donor milk come from a regional nonprofit bank certified by the Human Milk Banking Association of North America.

And the most basic idea behind the for-profit model — that paying women would increase the milk supply — is also shaky.

“There’s a really big range of normal milk supply. Some mothers will only ever make just enough,” Spatz, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said. “Mathematically, I don’t think paying them means that all of a sudden there’s going to be women with all this extra milk. You couldn’t take a mom who makes 400 milliliters a day and get her to produce one liter a day.”

Those who do sell their extra milk said the prospect of earning money wasn’t what drove them to pump.

“I’m not sitting there pumping to make money,” Clearwater, the mother who had sold milk to Prolacta, said. “I’m sitting there pumping to make food for my baby, and I have extra.”

A Year of Donor Milk

The last snowy chunks of frozen breast milk, given to her by a mother she found through Facebook, slid out of the plastic bag and into the Mason jar. Liz Lipman-Stern clapped a lid on top and screwed a ring around the rim, the metal grating softly on glass as a thick, creamy rivulet rolled down the jar’s inner wall. A few rooms away in the light-filled Brooklyn apartment, her then-8-month-old daughter, Julia, slept soundly.

Every day since her daughter Julia was born in February 2015, Lipman-Stern has checked at least five Facebook chapters of Human Milk 4 Human Babies multiple times. She and her husband, Rob Lederer, have driven endless hours to cobble together a supply of milk — 100 ounces here, 300 ounces there, and in rare cases more than 1,000 ounces of milk — to feed their daughter.

“Feeding my baby is one of the most important things in the world to me,” Lipman-Stern said. “I know that breast milk is the best thing for her.”

Now Julia is a thriving, wide-eyed 1-year-old who smiles and waves at her reflection in mirrors and windows and uses her emerging teeth to nibble happily on shreds of organic bread dipped in olive oil. Recently, she learned how to twist the neck of her rubber toy giraffe so it squeaks.

Since reaching her goal of feeding Julia breast milk for a year, Lipman-Stern has continued to give Julia donated milk when her daughter wants to drink it, along with solid food. She plans to gradually wean Julia off the milk, simply because it is so much work to procure, Lipman-Stern said.

And after that?

“We have two fertilized eggs frozen,” Lipman-Stern said. If she and her husband are able to have a second baby, again through a surrogate, she said she would try to re-lactate, a phenomenon experts said was rarely successful but not impossible.

And if that fails, she knows exactly which Facebook pages to check to find milk for her baby.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.