How Long Will Italy's Honeymoon With Draghi Last?

In Italy, politicians left, right and centre are rallying behind Mario Draghi's attempt to form a national unity government -- but will an unusually broad coalition make his job harder?

As a former president of the European Central Bank (ECB) and top official at Italy's treasury department, Draghi has experience with working with governments from across the political spectrum.

"He is the classic civil servant who adapts to different political circumstances ... which does not mean he does not have his own principles and values," Alessandro Speciale, a journalist and Draghi biographer, told AFP.

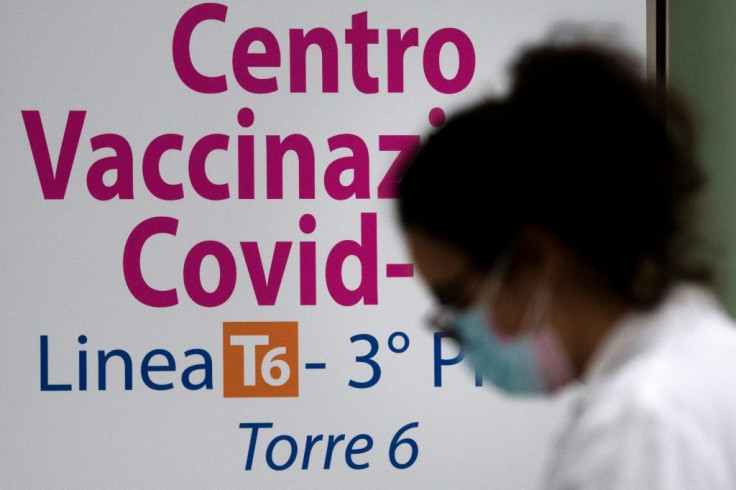

Draghi was asked by President Sergio Mattarella to seek a broad consensus for a new government facing Italy's worst health and economic crisis since World War II.

More than 91,500 people with coronavirus have died in Italy and nearly 450,000 jobs were lost during 2020.

Yet even for a man known as "Super Mario" for saving the euro while at the ECB, it may be a tall order to handle a coalition stretching from the left to Matteo Salvini's far-right and eurosceptic League.

Wolfango Piccoli, co-president of the Teneo consultancy, says Draghi has enough political capital -- at least for now -- to impose his own agenda.

On Sunday, a poll published by the La Repubblica newspaper said Draghi had overtaken outgoing premier Giuseppe Conte as Italy's most popular politician, with a 71 percent popularity rating.

"I don't think the League will be an issue," Piccoli told AFP.

He added that having Salvini on board could even help smooth relations with League-controlled regions, which often challenged the previous government's coronavirus decisions.

As prime minister, Draghi could also benefit from his experience leading the treasury department at the economy ministry throughout the 1990s.

"He knows how to work with the machinery of government," Veronica De Romanis, an economist who worked under Draghi at the ministry, told AFP.

"That's going to be his great advantage."

Draghi's own politics are hard to pigeonhole.

At the treasury in the 1990s, he worked on a large-scale privatisation programme and deficit-cutting efforts, to help Italy qualify to join the euro single currency.

Draghi backed the painful austerity measures that Italy's last technocratic government, led by Mario Monti, adopted in 2011-12 to pull the country from the brink of bankruptcy.

His career also owes something to Silvio Berlusconi, as it was under the billionaire's right-wing governments that he became governor of the Bank of Italy in 2005 and ECB president in 2011.

But as ECB president, Draghi challenged monetary orthodoxy and pro-austerity Germans, famously vowing to do "whatever it takes" to shore up the eurozone.

In March 2020, he advocated a similarly bold policy response to the pandemic, saying governments must take on more debt to support individuals and businesses.

"Faced with unforeseen circumstances, a change of mindset is as necessary in this crisis as it would be in times of war," he wrote in the Financial Times.

Draghi supports "a very strict regulation (of the markets) and a welfare state that offers protection to those caught out," Marcello Messori, an economist from Rome's LUISS university, told AFP.

As prime minister, Draghi faces a different task to Monti -- deciding not how to cut public spending but how to allocate Italy's share of the EU's post-virus recovery fund, worth more than 200 billion euros ($240 billion) in loans and grants during 2021-2026.

But this could also be tough, involving a restructuring of the economy and potentially unpopular reforms.

In August, in his first major speech since leaving the ECB presidency, Draghi warned: "Depriving a young person of the future is one of the most serious forms of inequality."

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.