How Much Do Doctors Make? How Trump's America Could Hurt Young Medical Professionals

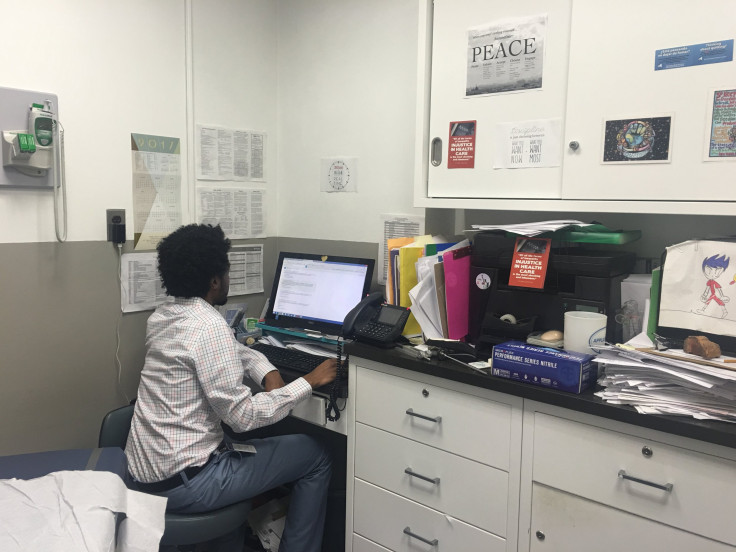

Dr. Danny Neghassi's cramped office pulls double duty as an examination room at the nonprofit Heritage Health Center in New York City's Harlem neighborhood. The counters are piled high with paperwork and the white cabinet doors are plastered with posters urging social activism. Taped up near his computer is a crayon drawing by one of his patients' grandchildren. He keeps a pigtailed Doc McStuffins doll at hand because a nervous young patient once told him she was inspired by the Disney character.

Though his space is small and his days are busy, 33-year-old Neghassi prides himself on treating more than patients' physical ailments — he says he tries to get to know them on a deeper level. It’s the kind of personal care that drew him to pursue nonprofit medicine despite its lower pay.

“It’s not a financial decision to go into medical school,” Neghassi told International Business Times on a recent day. “There are ways to make money faster and without years of debt.”

But being a physician at a federally qualified health center means that Neghassi’s income is directly tied to the whims of the federal government — something that worries him on the doorstep of President-elect Donald Trump’s Friday inauguration. The majority of the patients he sees are insured by Medicaid, meaning Neghassi's paycheck is wedded to funding for the low-income health care program. With the start of the Trump administration quickly approaching and the future of government funding uncertain, Neghassi has grown nervous about the financial impact the new president may have on physicians and patients alike.

Neghassi sees up to 20 patients a day for everything from routine physicals to family planning at the heath center, which is housed in a four-story brick building on the corner of Amsterdam Avenue and 145th Street. Patients crowded the waiting room at Heritage on a recent morning, though Neghassi wouldn't begin taking appointments for another few hours. Dressed in light blue pants and a white checkered button-down, he arrived early to catch up on piles of paperwork -- a side effect, he said, of the convoluted insurance system.

A lifelong New Yorker, Neghassi said he chose to take the charitable route as a student at Columbia University after learning people in certain areas couldn't access quality medical care because they didn't make enough money. That started him down a path to becoming a physician in nearby Harlem, where he lives with his wife. Before long hours at the health center, he stops at a nearby coffee shop, Il Caffe Latte, for a drink. A short walk to work each morning and a home in the community allows Neghassi to be immersed in the needs of local patients.

When he's not doing checkups alongside Doc McStuffins, Neghassi devotes nearly all his free time to advocating for health care causes. Neghassi has lobbied for single-payer health care and organized rallies for expanded Medicaid. A self-described “doctor, husband, son, brother, citizen and human,” Neghassi also volunteers at the Columbia-Harlem Homeless Medical partnership, a student-run clinic in a church basement near his office.

“Helping people who wouldn’t otherwise have help is very rewarding,” he said as he sat on a small wheeled stool behind his desk, the only seat in his cramped office.

But Neghassi still needs to pay his bills — namely, the ones for the student loans he racked up while pursuing his dreams in medical school. The typical student graduates from medical school owing nearly $167,000, and Neghassi is no exception. Though he describes his loan total as “less than average,” it’s unlikely to be repaid quickly through his job at Heritage.

Family doctors already rank as the third lowest paid in annual incomes among all doctor specialties, behind only pediatrics and oncology, and family physicians at community health centers make even less. They average about $164,000 per year, according to an industry survey by Payscale.

For help, Neghassi has applied for the National Health Service Corps Scholarship, a Department of Health and Human Services program that awards loan repayments in increments of $50,000 for every two years of nonprofit work. But funding for any such government program is never a sure thing. Trump has nominated Tom Price as secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, the branch of government that oversees the scholarship loan, and Neghassi said he's greatly concerned about the pick. If Price is confirmed, he’d be responsible for funding decisions that could impact programs like the student loan scholarship.

Neghassi has also become increasingly worried about the imminent repeal of the Affordable Care Act — a stance that sets him apart from many physicians, who have repeatedly indicated in surveys they disapproved of Obamacare. Neghassi is paying special attention to what happens with the insurance law because the expansion of Medicaid under Obamacare generated an additional $2.1 billion in revenue for community health centers in 2014 alone, according to a study conducted by the Milken Institute, an independent economic think tank in Santa Monica, California. That money went, in part, toward paychecks for doctors and nurses.

Trump has plans for Medicaid that look vastly different than its current expansion. In a health care outline released during his campaign, Trump said he wanted to block-grant funding for the program, which would give a set amount of funding to states to use as they see fit. Trump has not explicitly mentioned how big or small his grants would be, so the future of funding is still uncertain — yet another matter in Neghassi's mind as he looks at his bank account.

The increased funding under Obamacare used to pay doctors and other staff at neighborhood centers could disappear under Trump's plan, virtually eliminating certain jobs for doctors that communities like Harlem depend on. What's more, fewer of Neghassi's patients could have access to Medicaid insurance, meaning they might wait until their illnesses become dire before seeing a doctor, simultaneously harming their health and driving up costs. Emergency care costs far more for a health center than preventative care does, funneling necessary funding into crisis treatments that could instead be used for other purposes.

“Generally, there is always a market for doctors,” Neghassi said. “My main concern is people’s access to affordable health care – particularly women, low-income communities and immigrants.”

Urging all to support #NYHealthAct #singlepayer @ #Harlem Hosp. Too many patients struggle, w/ or w/o insurance pic.twitter.com/rUNPbaoeer

— Dr. Danny (@neghassi) April 14, 2016

In the face of this ambiguity, Neghassi has stepped up his activism with Physicians for a National Health Policy, a group that lobbies for a more efficient, streamlined single-payer health care system that would create an insurance initiative funded through taxes scaled based on income.

A comprehensive single-payer health care plan would change insurance as a whole, but it would also directly benefit the salaries of doctors like Neghassi by shrinking the disparities among physician specialties and raising incomes for doctors who see mostly Medicaid patients. Trump has previously acknowledged that single-payer health care works abroad, but it's not clear whether he would accept it in the U.S.

For Neghassi, health care reform is necessary, but it needs to do more good than harm, just like he vowed to do when he became a doctor. As he sat in his office on a recent day, he had a full slate of patients and early morning work to do. Beneath a small sign carrying the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. quote, "Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in healthcare is the most shocking and inhumane," Neghassi flipped through mounds of lab work for his patients, preparing for the many he would see later in the day. Fidgeting in his chair, he arranged bills, medical paperwork and insurance forms into precarious towers next to his computer.

“Community health centers have existed for decades, so I don’t think there’s going to be an effort to close them down by the numbers,” he said as he worked through his stack of papers. “But there are so many things being said as soundbites, and I don’t know how that translates to policy.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.