Is This How Wall Street Cleans Up Its Act? Badly Behaved Banker List Raises Concerns

An effort is underway to create a master list of Wall Street bankers who have run into ethical issues on the job. The proposed database, first reported by Bloomberg, would help companies avoid hiring repeat offenders who have a habit of jumping from firm to firm.

But advocates of stronger ethics on Wall Street question whether it’s possible to change behaviors without changing incentives.

“In many financial institutions there’s a disconnect between what the bank says and what is actually being done,” said Jordan Thomas, chairman of the whistleblower defense practice at law firm Labaton Sucharow. Even when employees face companywide ethics guidelines “the structure in which they are working puts pressure on them” to break rules, Thomas added.

The idea for a registry of misbehaving bankers originated in the U.K., where a similar system was launched in September. In the U.S. the proposal has earned the backing of New York Federal Reserve President William Dudley, who floated the idea at a recent gathering of bankers and financial regulators devoted to reforming Wall Street culture.

Attendees at the New York Fed event evidently took to the proposal. Industry players “noted a problem of blind recruitment and argued for a searchable database as a solution,” according to an official summary of the November meeting.

“It would totally make things a lot easier to easily screen out applicants,” said Peter Laughter, chief executive of the recruiting agency Wall Street Services. Although Laughter said the registry would be beneficial, he also said industry inertia would eventually push back.

“Most of my clients have an official policy of not giving out references,” Laughter said of the establishment Wall Street firms he works with. “If they’re not giving out references, are they going to give out private employee records of alleged abuses to a regulator?”

The effort is just one facet in the New York Fed’s ongoing effort to improve Wall Street culture and rectify what Dudley has called “an apparent lack of respect for law, regulation, and public trust [that] persists within some large financial institutions.”

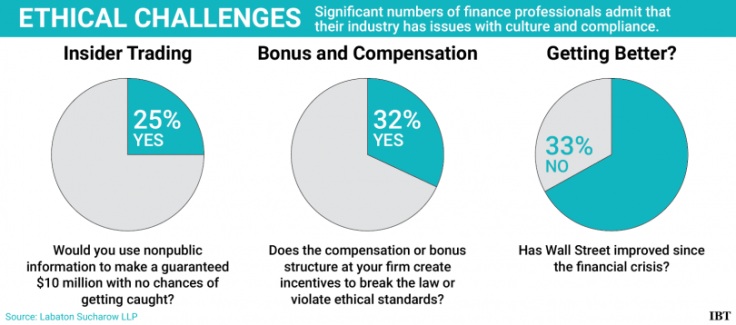

And there’s no doubt that many in the banking world have reason to worry about the moral rectitude of their industry. In a survey conducted by Labaton Sucharow earlier this year, 1 in 4 bankers said they knew co-workers who had run afoul of the law. Nearly a third of those surveyed said bonus and compensation incentives encouraged malfeasance.

The proposal also runs the risk of giving Wall Street managers the opportunity to exploit the registry in order to discourage the kind of whistleblowing that the Securities and Exchange Commission has promoted since the financial crisis.

“Greater transparency regarding the participants in the financial markets is always good for investors,” said Thomas, who was previously a litigation counsel at the SEC. “However, great care would need to be taken in the details of such a program because of the potential for abuse.”

Thomas cited cases of banks retaliating against brokers for blowing the whistle on wrongdoing, using a database similar to the one being floated for the wider banking industry. The registry, run by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), an industry self-regulator, stores the disciplinary records of financial advisers. A negative mark next to someone’s name in the database can make it virtually impossible for that person to find a job.

A recently publicized case involving the FINRA database illustrates Thomas’ concerns. After former JPMorgan broker Johnny Burris raised a red flag over the bank’s disclosure practices surrounding conflicts of interest in investment advice — lapses the bank recently paid more than $300 million to resolve — two damaging client complaints appeared on his record.

The complaints were signed by former clients of the broker, but as the New York Times later reported, it was JPMorgan employees who actually wrote them. One former client told the newspaper that she had “no problems whatsoever” with Burris and signed the complaint, without reading it, at the behest of the bank.

Unlike the broker registry, however, the banker database as proposed would be sealed from public view, accessible only to managers and executives. But that doesn't allay concerns that the new database could be misused.

The inevitable conflicts that would arise make Laughter skeptical that the proposal would fly.

“Even if it does get off the ground, someone who’s on the naughty list will get word of that, and they’re going to sue,” he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.