How Washington took the US to the brink and back

The world's largest economy was headed toward an unprecedented default, and all Washington wanted to talk about was the manner in which the president had left a room.

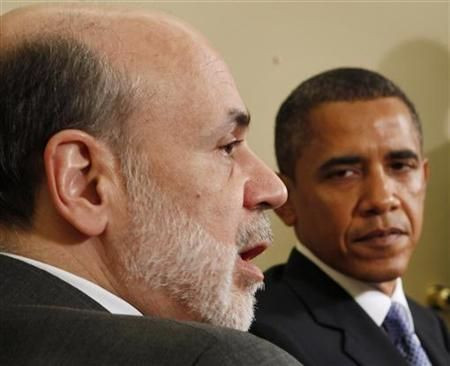

A White House meeting in mid-July between President Barack Obama and congressional leaders had ended with sharp words as Obama clashed with the brash Republican House majority leader, Eric Cantor. Now Cantor was back on Capitol Hill, dishing details to a scrum of reporters -- a shift from the terse, vague statements that usually followed such meetings.

"He said to me, 'Eric, don't call my bluff. I'm going to the American people with this,'" Cantor said in his Southern drawl. "I was somewhat taken aback."

Republican aides filled in the gaps. Obama had "stormed out of the room," one said. At the White House, aides pushed back. One official demonstrated to reporters exactly how Obama had ended the meeting -- lightly pushing his chair back from the table, standing up deliberately, walking away calmly. "He didn't storm out. He just got up and walked into his office," one said.

That evening -- July 13, 2011 -- was one of the lowest points in the struggle to avert fiscal disaster and put the nation's budget on a sustainable path. Congress needed to extend the country's $14.3 trillion debt ceiling before Tuesday, Aug. 2, the date the Treasury Department would begin running out of cash to cover the country's bills. But Republicans and Democrats were deadlocked.

INSIDERS UNITE

As the deadline drew closer, the two sides abandoned a series of efforts to reach agreement, searching for the right combination of policies and personalities to get a deal done. In the end, it fell to two consummate Washington insiders to prevent the talks from collapsing. A Reuters examination of the months-long showdown over the debt ceiling found that:

* Vice President Joe Biden and Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell emerged as critical players in the final stretch of the talks, as theirs was the only cross-party relationship built on decades of trust.

* Despite a belief among many rank-and-file Republicans that the government could muddle through a default, party leaders never doubted the Treasury Department's warnings that economic catastrophe was a real possibility if they didn't reach a deal by Aug. 2.

* Although House of Representatives Speaker John Boehner, the top U.S. Republican, was eager to strike a bold deal with Obama, it was ultimately necessary for Boehner to distance himself from the White House to convince his House Republicans to back the final deal.

* The business community played an important behind-the-scenes role, with two White House foes -- Wall Street and the Chamber of Commerce -- rallying support for a compromise backed by Obama.

This account of America's journey to the brink of default is based on interviews conducted over the past six weeks with dozens of elected officials, business lobbyists and aides in the House, the Senate and the White House.

A ZEAL FOR CUTS

The U.S. congressional elections in November 2010 set the stage for confrontation over the congressionally mandated cap on the outstanding total of federal government borrowings. Republicans had harnessed voters' anxiety over the economy and soaring deficits to capture the House of Representatives.

Accusing Obama of overreaching with his stimulus package in 2009 and his drive for healthcare reform, Republicans vowed to slash spending and rein in the federal government's size. A campaign document -- the "Pledge to America" -- promised to cut spending by $100 billion in the first year alone, back to the levels in place in Republican President George W. Bush's last year in office.

The newly elected Republicans, 87 in all, were not interested in compromise. Many felt a greater obligation to the grassroots Tea Party activists who had sent them to Washington than to the party elders who ran the place. In a budget fight with the Democratic-controlled Senate that took the government to the brink of a shutdown in April, Republicans managed to cut spending by $38 billion, the largest domestic cut in U.S. history. Still, 59 House Republicans voted against the bill because it did not go far enough.

BOEHNER'S BATTLELINES

That was a mere skirmish. The big battle lay ahead as the government was fast running up against its $14.3 trillion credit limit and would need Congress to raise it further. In early May, Boehner laid out his conditions for a debt-ceiling increase: spending cuts would need to exceed the amount of new borrowing authority.

Instead of billions of dollars, the debate would be measured in the trillions. It would be a chance for Boehner to show his new troops that he could use the levers of Washington to get results. An avid golfer and a chain-smoker, the 61-year-old Boehner is from an older generation than many of the Tea Party conservatives whose election to Congress made it possible for him to become House Speaker.

The seasoned legislator and former businessman grew up in Ohio from a family of modest means and worked as a janitor to help put himself through college. Obama, 49, had a comfort level with fellow Midwesterner Boehner despite their philosophical differences. The speaker reminded the president, a former state senator from Illinois, of Republican legislators he used to play poker with in Illinois and with whom he forged bipartisan deals.

Both men are even-tempered and view themselves as Washington outsiders. Each has ambitions of transforming Washington and making a big mark on policy.

Those aspirations drove their on-again, off-again talks aimed at a far-reaching, bipartisan "grand bargain" that would put the United States on sounder fiscal footing for years to come.

On a golf outing in mid-June, the two agreed to work together on a broad deficit-reduction deal. "Let's give it a try," Obama told the speaker.

The following week, at a secret White House meeting, they agreed to have their staff draw up options. The aim was to craft a plan that would cut deficits by roughly $4 trillion over 10 years.

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.