Hubble Finds New Clue About Possible Water On Trappist-1 Planets

Images from the Hubble Space Telescope have led researchers to believe there might be water on the exoplanets that orbit the Trappist-1 star in the habitable zone, according to a press release from NASA and the European Space Agency.

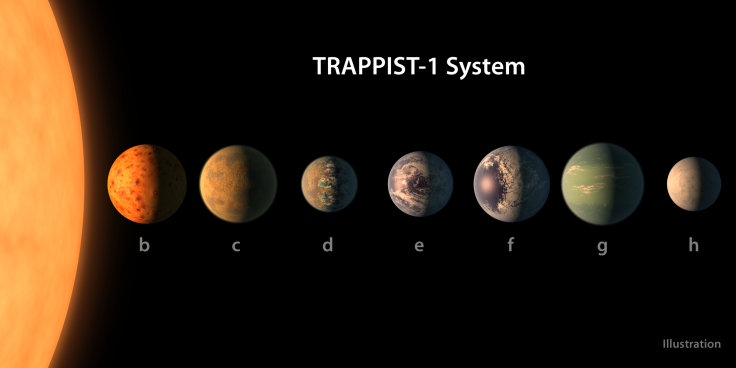

In February, NASA announced the discovery that the Trappist-1 star that sits nearly 40 light years away from Earth has seven Earth-size planets that orbit it, three of which are in the habitable zone. After the announcement, a team of international researchers began studying the ultraviolet radiation to which the planets in the system are exposed.

The strong ultraviolet light can cause water molecules made of hydrogen and oxygen to break up and escape the atmosphere into the space around the planet. Hubble is sophisticated enough to detect the hydrogen around a planet that could be an indicator of water. Based on the amount of ultra-violet radiation Trappist-1 gives off the planet that orbit it could have lost oceans worth of water over billions of years.

If the planets currently, or in the past, had water, they would all lose it at different rates. While all of the planets would have some level of release, the two planets that are closest to the star would have lost the most water due to their close proximity to the star and high exposure to radiation. During the last eight billion years the two closest planets, Trappist-1b and Trappist-1c could have potentially lost more than the equivalent of 20 times the oceans on Earth. But those further out and in the habitable zone, Trappist-1e, Trappist-1f and Trappist-1g, would have lost far less water than that if they do have water. Meaning those planets could potentially have water on the surface.

While this new finding is promising for the outermost planets, it’s a hypothetical situation, so more research is necessary to discover whether the planets do actually have physical water on them currently. NASA is expecting to launch the James Webb Telescope in October 2018 to further study Trappist and the stars in the system.

The telescope will extend the work of Hubble by observing and collecting data in longer wavelengths than Hubble can. This will help researchers learn far more about the atmospheres of the Trappist planets and whether or not there might be water vapor present in them. The telescope will be able to analyze light using a method called spectroscopy, meaning it will analyze the light in wavelengths to detect specific chemical signatures. Currently, the telescope is frozen in a cryochamer at Johnson Space Center in Houston where Hurricane Harvey recently dropped feet of rain causing historic flooding. The telescope is unharmed by Harvey.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.