Huge ‘Cold Front’ Hurtling Through Distant Galactic Cluster At 300,000 MPH

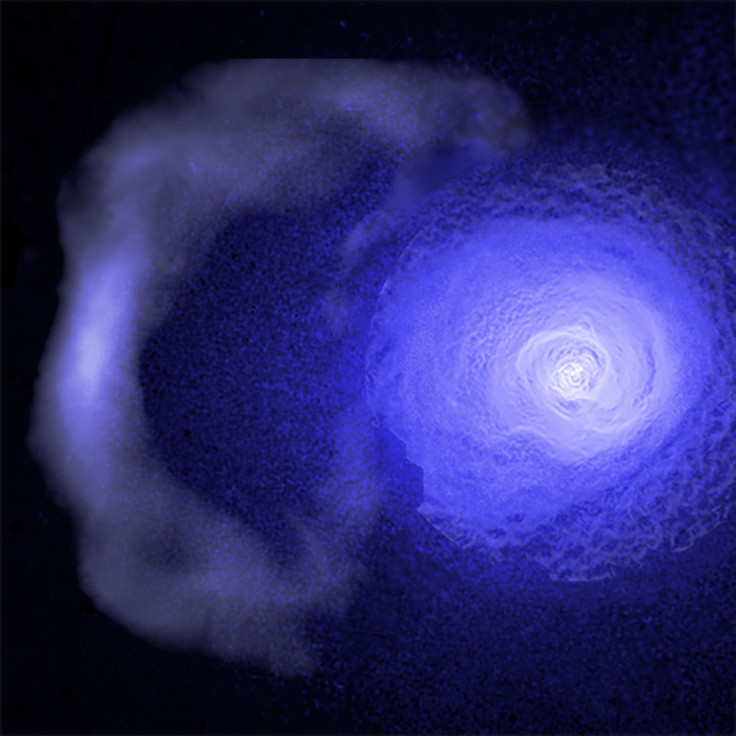

Astronomers at NASA have taken a close look at a strange cosmic weather system – a “cold front” that spans about two million light years and has been hurtling through one of the largest objects in the universe, the Perseus galaxy cluster, for more than five billion years, which is longer than the existence of our solar system itself.

The weather system, first discovered in 2012, carries a dense band of “cool” gas with a temperature of about 30 million degrees moving through lower density hot gas, heated to about 80 million degrees. It has been rippling through the cluster at 300,000 miles per hour and was recently imaged by the space agency’s Chandra X-ray Observatory.

During this observation, the front looked nothing like what NASA expected. Scientists at the agency thought the system, while hurtling through Perseus for several billion years, might have witnessed the impact of sound waves and turbulence from the supermassive black hole at the center of the cluster. It should have made the system fuzzy at the edges, but the results show something exactly opposite.

“Somehow, in the face of all this bombardment, the cold front edge has survived intact,” John ZuHone of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, said in a NASA statement. “Rather than being eroded or smoothed out, it has actually instead split into two distinct sharp edges!”

Though the exact reason behind such resilience remains unknown, the astronomers who studied the Chandra observations think it could be the work of a magnetic field wrapped around the front. According to the team, this field is acting as a shield and protecting the humongous weather system from the impact of external cluster forces.

To understand how powerful a field like this could really be, the group ran computer simulations testing the impact of three different levels of magnetic fields. In this, the impact of the strongest and weakest magnetic field did not work, but the one with intermediate strength reproduced the split cold front.

This, as the space agency noted, is nearly ten times higher than fields prevailing in other parts of the cluster, far from the front. “The size, age, speed and sharpness of this cold front are remarkable,” NASA’s Stephen Walker, who led the study, said in the same statement. “Everything about this cosmic weather system is extreme.”

Unlike cold fronts on Earth, these systems are driven by the collision between galactic clusters. Whenever a small cluster is pulled towards the core of a bigger one, the gravitational force between the two causes the gas in the core to move producing a spiral-shaped cold front.

The observation will be detailed in a paper set to be published in journal Nature Astronomy and is available for online access.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.