Hurricanes Have A Lot Of Energy -- So Why Aren't We Harvesting It?

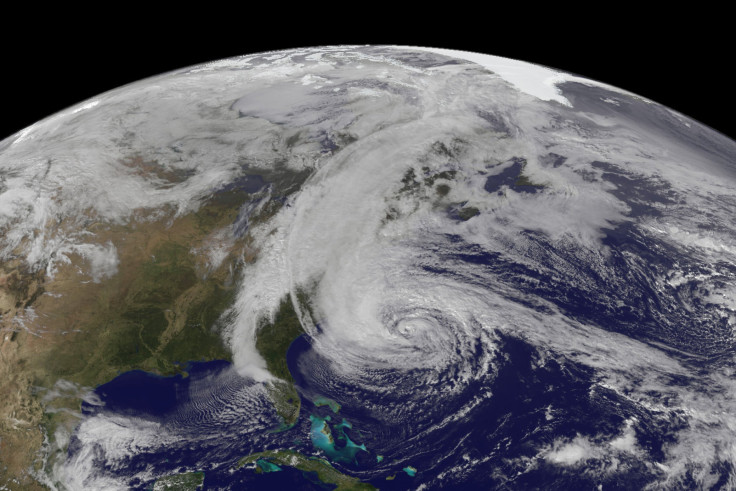

Tropical Storm Andrea is ushering in the 2013 Atlantic hurricane season this weekend, delivering heavy rains and the threat of power outages to towns all along the East Coast. But could a hurricane ever restore power, instead of taking it away? If wind power is one of the great green energy hopes of the future, why not look to the fiercest storms?

Hurricanes do pack a lot of power. Thanks largely to its immense size, the total energy of Superstorm Sandy (what researchers call the “integrated kinetic energy”) was pegged at about 140 terajoules, or about twice the energy released by the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. That’s a lot of energy, but it’s not atypical for a hurricane, according to University of Miami meteorologist Brian McNoldy.

“At any given moment, many hurricanes contain more energy than an atomic bomb in their surface winds alone (even excluding winds at higher elevations and latent heat energy),” McNoldy wrote in the Washington Post last November.

While that might sound like an untapped resource, at present most scientists say it’s pretty much infeasible to use current wind farm technology to harvest all that power. Hugh Willoughby, a Florida International University hurricane expert and former research meteorologist for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is especially skeptical -- to put it mildly.

“The notion is utter nonsense,” Willoughby wrote in an email.

He points out that to avoid damage, “wind turbines feather their vanes” -- turn the edges into the direction of the wind -- “in winds stronger than gale force," or about half a hurricane's force.

In the middle of a hurricane, the turbine’s blades would stop rotating, once feathered, and the turbine would shut down. Not a great business model.

“Anything you design to harvest hurricane winds would have to be a whole order of magnitude more robust and designed specifically for that purpose,” NOAA hurricane researcher Neal Dorst wrote in an email.

Even if there was a turbine that could withstand the gale, Willoughby points out that hurricanes are episodic -- they come and go, with no certain path. Placing ground-based machines is no guarantee that they’ll lie within a storm’s path.

Plus, “how would one get the energy [from] the hurricane to the power grid?” Willoughby asked. “It’s not feasible to store that amount of electricity.”

Another technical impediment to harnessing hurricanes is that their energy, while massive, is spread out over a very broad area.

Any hurricane power venture “would need a field of wind turbines covering dozens of square miles in order for it to be profitable,” Dorst wrote on the agency’s website. “And it would have to be mobile, so you could intercept landfalling storms, or chase those that change direction. Of course, you have to expend energy to move them around, so you run the risk of losing money on the operation.”

Nevertheless, some power companies have found other ways to make hay from hurricanes and other storms. In 2008, The Woodlands, Tex.-based Biofuels Power Corp. started a project to convert wood chips and other wreckage from areas damaged by Hurricane Ike into electricity.

Another approach would be to make the storms come to us -- by creating them. Canadian engineer Louis Michaud has been working on an “atmospheric vortex engine” that essentially creates a tornado inside a cylindrical wall.

But -- perhaps unsurprisingly -- Michaud has had trouble pitching the idea of a homegrown tornado to investors. Plus, he “must navigate the cultural divide between atmospheric scientists and the weather-modification community,” The Economist noted in 2005. “The scientists regard the weather-modification crowd as cranks.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.