IBM Stock: Warren Buffett’s Investing Philosophy Tested By Berkshire Hathaway’s Ongoing Stake In Big Blue

Warren Buffett isn’t known for blown calls. But the billionaire investment guru and head of the holding company Berkshire Hathaway has become increasingly touchy around one of his top positions: International Business Machines.

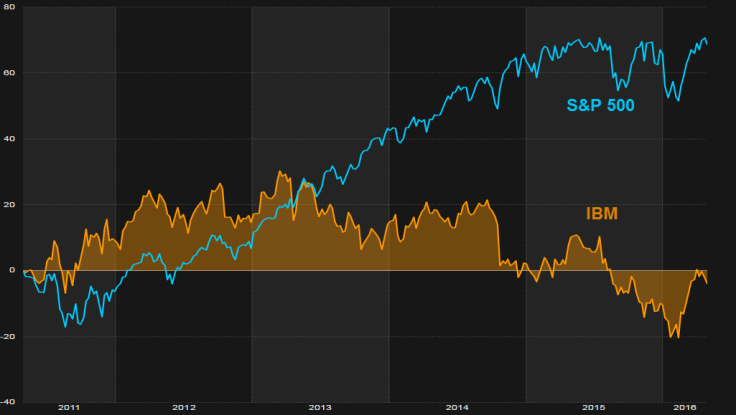

“We feel fine or we won't own it. We've never sold a share of IBM,” Buffett told CNBC in an interview Monday. The fact that shares in the computing giant have fallen some 15 percent since he started building his stake in the company in early 2011 hasn’t phased him. “Periodically, we buy a little bit more,” he added.

Buffett’s persistence with IBM is characteristic of the executive, who favors long, steady positions in reliable, well-led companies. The strategy has produced historic gains. In the past 50 years, Berkshire's stock has appreciated at an average clip of 21 percent a year, while the broader Standard & Poor's 500 has climbed 9.9 percent annually.

But Berkshire’s $11.7 billion stake in IBM has tested crucial tenets of Buffett’s investing philosophy: namely, a balance between shareholder-friendly payouts and a core business model built on growth and stability.

From 2000 to 2015, IBM gave nearly $200 billion back to shareholders in the form of dividends and stock buybacks, equaling 110 percent of net income. During the same period, spending on research and development totaled $92 billion.

That imbalance between shareholder payouts and investments in organic growth has attracted greater scrutiny as Big Blue has lagged behind its competitors in reorienting for a digital age where cloud computing and mobile technologies dominate.

Buffett’s feelings on such payouts — particularly buybacks, which have far outstripped IBM’s dividend spending — are mixed. As a shareholder, Buffett lauds corporations that return cash via dividends and buybacks, the latter of which can support stock prices. But as a value investor, Buffett is wary when management allocates cash in ways that benefit themselves in the short run through improved performance pay metrics.

“We like increased dividends, and we love repurchases at appropriate prices,” Buffett wrote in a 2012 annual letter. But 13 years earlier, he had voiced apprehensions. “Now, repurchases are all the rage, but are all too often made for an unstated and, in our view, ignoble reason: to pump or support the stock price,” Buffett wrote in an oft-cited 1999 letter, which came during the first great wave of corporate buybacks.

While it made sense for companies to repurchase shares when they were trading at a steep discount, Buffett said, buybacks that merely help line the pockets of managers are no help. The question for IBM, then, is whether its buybacks have benefited long-term shareholders looking for sustained growth, or actually come at their expense.

IBM has been among the top companies in returning cash to shareholders, but its pace of buybacks accelerated in 2010, after then-chief executive Sam Palmisano announced a plan to double earnings per share by 2015, while doubling down on software and analytics investments.

That strategy hinged on buying back billions of dollars in stock. By reducing outstanding share counts, companies boost earnings per share figures. That helps both existing shareholders, who earn a bigger chunk on future profits, as well as managers like Palmisano and his successor Ginni Rometty, whose bonuses are tied to earnings per share totals.

But the earnings side of the equation didn’t fare so well. The second quarter of 2012 saw the beginning of a string of quarterly revenue declines that, 16 quarters later, have not let up. First-quarter revenue for 2016 was the lowest in 14 years.

In the last year, however, IBM has pivoted away from stock buybacks, which declined from $13.7 billion in 2014 to $4.6 billion in 2015, with approximately the same amount expected in 2016. In March, the company revised its executive compensation program to remove potential benefits to Rometty’s pay from unplanned repurchases.

Research and development spending remained unchanged, however, while acquisitions increased. Last week IBM upped its dividend by 8 percent.

IBM denies that high payouts to shareholders come at the expense of capital investments. Company spokesman Ian Colley pointed to a 2014 op-ed by IBM Chief Financial Officer Martin Schroeter calling the division a “false choice.” Though IBM aims to maintain research spending at 6 percent of total revenue, that ratio dipped to an average 5.85 percent during the five years with the highest buyback activity.

As for research initiatives, Colley noted IBM’s recent forays into the bitcoin-related technology blockchain and Watson, IBM’s famed artificial intelligence project. Defending Berkshire’s IBM investment, Buffett’s longtime second-in-command Charlie Munger also mentioned Watson on Monday. “I like the idea of using artificial intelligence because we are so short on the real thing,” he said.

Whether Watson and similar initiatives will be enough to pull IBM out of its funk remains unclear, but IBM’s core businesses remain strong. A central player in the world’s technological infrastructure, IBM manages some 70 percent of the world’s business data, according to Schroeter. But much of that business is migrating to the cloud, where newer companies like Amazon have carved out a substantial market share.

In his 2012 letter to shareholders, Buffett shared a piece of advice attributed to Munger. It is “far better to buy a wonderful business at a fair price than to buy a fair business at a wonderful price,” Buffett said. “Despite the compelling logic of his position, I have sometimes reverted to my old habit of bargain-hunting, with results ranging from tolerable to terrible.”

Which category IBM falls into remains up for debate. “What you pay for a stock doesn't mean anything. What means something is where the company's going to be in five to 10 years,” Buffett said earlier this year. “I think IBM will be worth more money but, like I said, I could be wrong. But we'll accept that.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.