Indigenous Colombians Fret As Sacred Mountain Glaciers Melt

In the shade of a sacred tree, Indigenous wise men chew coca leaves as they mull the threats to their home among the melting, snow-capped peaks of Colombia's Sierra Nevada mountains.

As a "consequence of man's actions, it is slowly warming, more every year," one of the men says in the Iku language, according to a translator, at a meeting of dozens of Indigenous people from different communities.

The inhabitants of the Sierra Nevada range in north Colombia believe it is the center of the universe, its rivers, stones and plants part of one living body. They see it as their job to protect its balance.

In 2022, UNESCO recognized the ancient knowledge of the area's four Indigenous groups as part of the world's intangible cultural heritage, and essential to caring for "mother nature, humanity and the planet."

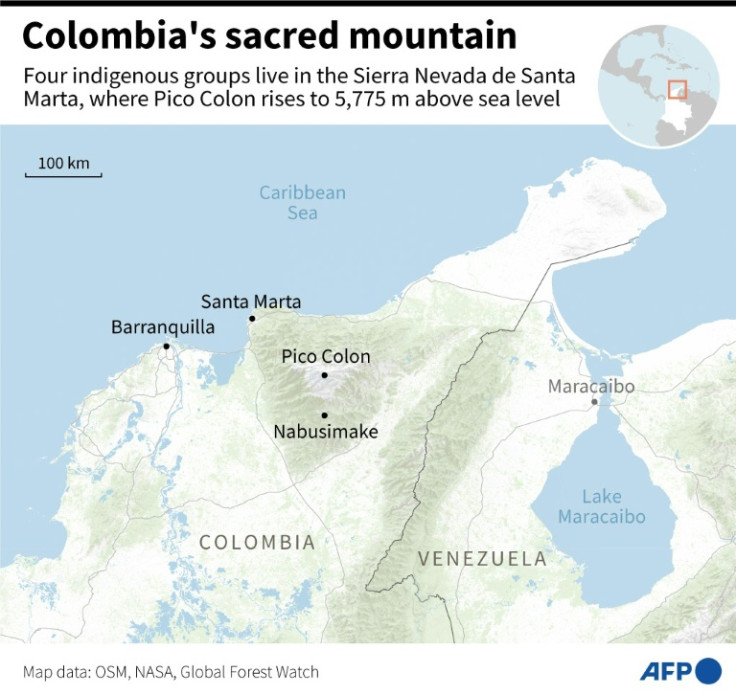

But here in Earth's highest coastal mountain system, 5,775 meters (19,000 feet) above sea level, the natural harmony they prize is being disrupted as record heat waves melt the glacial peaks and ruin their crops.

In a form of active meditation, the Arhuaco spiritual leaders or "mamos" place a wooden stick in their mouths before removing it and rubbing it around a gourd -- transferring their thoughts to the hollowed-out fruit.

"We are here to live in peace, in harmony. Believing otherwise leads to global warming," one Indigenous leader says.

"Man is going to end himself because of his own inventions, believing himself to be very intelligent."

Of the 14 tropical glaciers that existed in Colombia at the beginning of the 20th century, only six remain, according to official data.

The Sierra Nevada's glacial area has shrunk from 82 square kilometers (32 square miles) in the mid-19th century to just 5.3 kilometers in 2022, according to the state meteorological institute.

The Arhuaco live in the Sierra Nevada alongside the Kankuamo, Kogui and Wiwa peoples, who are distinct but related communities.

They wear white tunics and hand-woven white straw hats. When greeting each other, they exchange handfuls of toasted coca leaves which they chew with lime to release stimulating alkaloids.

Their fears about the changing climate are shared by Leonor Zalabata, the first Indigenous person to represent Colombia at the United Nations.

"All the glaciers that existed in the Sierra Nevada are disappearing," she warns.

Seydin Aty Rosado, a leader in Nabusimake, a town of 8,000 people, said it used to be too cold to cultivate the coffee, bananas, and cassava they now plant.

In January, environmental authorities recorded a record temperature of 40 degrees Celsius (100 degrees Fahrenheit) in the seaside city of Santa Marta, at the foot of the Sierra Nevada.

A swing between morning frosts and midday surges of heat ruined the residents' maize crops.

The Arhuaco hope the weather extremes will moderate by March in time to plant beans, cabbage and corn.

"It is a response to what we as human beings have given to Mother Earth," said Rosado, as she handweaves a bag.

"Here is our past, our present and our future. When I weave, I talk and think about my children. Everything is recorded here, in the bag," she said.

One of the tenets of the community's worldview -- which they believe could help the world tackle climate change -- is collective thinking.

"There is only one man, only one woman. That's why if something happens to a man, wherever he is, he is connected to everyone. Likewise with women," explains Rosado.

"We are not alone, nor separated from other human beings, nor from animals, nor from anything that exists on Earth."

Aside from their deep connection with nature, the Arhuaco also highlight the importance of balance.

While they maintain their traditional clothing and beliefs, they carry cellphones in their woven bags, and use solar panels to electrify their mud huts.

They learn Spanish from childhood and some families send their children to study at public universities in neighboring cities.

"We believe that life is possible, as long as there is a balance," said Zalabata's son, Arukin Torres.

"Hence our insistence that we cannot alter the environment any further."

But climate change is not the only threat to the Arhuaco's environment.

Due to its rugged geography and proximity to the coast, the sacred mountain has for decades been a refuge and corridor for drug traffickers.

Torres also warns of a surge in paramilitary activity in the region as peace talks between armed groups and President Gustavo Petro's government hit a logjam.

"This crisis (of violence) is coming again. That is why we ask that the government resume its dialogue," he said.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.