Indonesian Presidential Candidate Evokes Dictator's Era

Maria Catarina Sumarsih protests weekly near Indonesia's presidential palace, hoping to get justice for her university student son who was shot dead by the army after the 1998 fall of dictator Suharto.

Her demonstrations since 2007 have sought answers about Wawan's killer from top officials who presided over the military's bloody crackdown on protesters demanding political reforms.

While Wawan was shot by an army bullet, according to an autopsy, no military leader has been held responsible for his death.

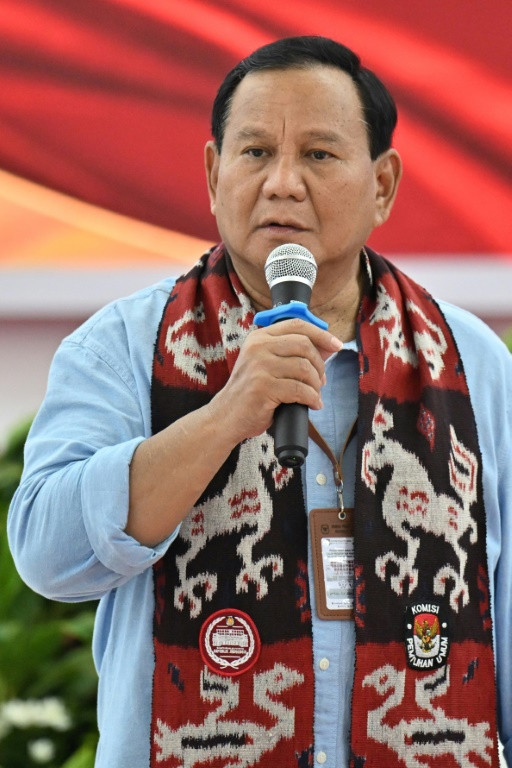

One from the Suharto era, former special forces general and current Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto, is now a leading contender in next year's Indonesian presidential election.

The 72-year-old candidate has rehabilitated his image in a bid to lead the world's third-biggest democracy.

After losing two previous presidential runs, Subianto's third attempt will have President Joko Widodo's son as his running mate -- potentially boosting his appeal.

Subianto remains accused of human rights abuses and ties to the Suharto family, as an ex-husband of one of the dictator's daughters.

At a recent protest, Sumarsih and 15 other activists carried a banner with images of alleged rights abusers, all former generals, including Subianto.

"I hope Indonesians will open their eyes and their hearts so they can see that people with blood on their hands should not be allowed to lead our nation," Sumarsih, 71, told AFP.

NGOs and former bosses accuse Subianto of ordering the abduction of democracy activists towards the end of Suharto's three-decade rule.

Some of those activists have never been found, and witnesses accuse his military unit of committing atrocities in East Timor.

Wiranto, an Indonesian military chief in 1998, blamed Subianto for the kidnappings.

Subianto was dismissed from the military over the abductions, several months before Wawan's death.

He has partly admitted a role in the disappearances but never fully taken blame.

"I carried out operations that were legal at the time. If a new government said I was at fault, I was here to take full responsibility," he said in a 2014 Al Jazeera interview.

After being discharged from the military, Prabowo went into self-exile in Jordan. He was also denied a US visa, although the official reason was never made public.

Between 1997 and 1998, when some kidnappings took place, Subianto led the elite army force known as Kopassus, used by Jakarta for special operations aimed at tamping down internal unrest.

Kopassus was accused of rights abuses in secessionist hotspots East Timor, Papua and Aceh.

Activists now worry that Indonesians could face worsening human rights if Subianto is elected.

"We are concerned that he may restrict rights, such as freedom of speech, assembly, the press, and other civil rights," said Amnesty International Indonesia executive director Usman Hamid.

"This can bring more social unrest."

The kidnappings Subianto is accused of orchestrating took place ahead of violent anti-government riots in 1998 that led to Suharto's resignation.

According to the Commission for the Disappeared and Victims of Violence, or Kontras, 23 activists were kidnapped between 1997 and 1998.

Nine were found alive, one was found dead and 13 are still missing.

The spectre of that unrest has been raised at least once since, and Subianto was at its centre after his 2019 election defeat.

Several protesters were shot dead, allegedly by police, as violence erupted in the wake of his loss and refusal to concede.

Subianto's nephew, also deputy chairman of his Gerindra party, did not respond to an AFP request for comment.

Experts say Subianto's popularity is partly due to styling himself as a populist, with many young voters unaware of his alleged rights abuses.

"It's not considered an important thing to influence the presidential candidate they will vote for," said Alexander Arifianto of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

Subianto, who studied in London and comes from an elite Indonesian family, has reached out to the youth via savvy social media tactics.

He shares images of his cats to his six million Instagram followers, while videos of him dancing have gone viral.

But Amnesty's Hamid believes Subianto must address the far weightier human rights issues.

"It's time for Prabowo to acknowledge the truth, despite potential uproar," said Hamid.

"It's an opportunity for him to demonstrate statesmanship."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.