Infected By Covid, Colombian Doctor Stared Death In The Face

Colombian doctor Norberto Medina has lived all facets of the coronavirus epidemic.

He has seen patients die and nursed others back to health. He contracted the virus himself, stared death in the face in intensive care, and donated blood plasma containing antibodies with which to treat others afflicted.

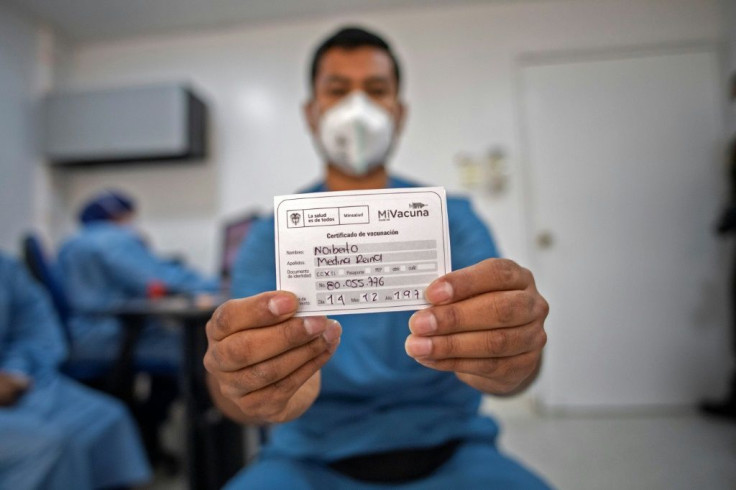

He has also received the vaccine.

With some persisting effects of his Covid-19 infection, Medina is back on the job, treating ailing patients at an intensive care unit (ICU) in the capital Bogota, Colombia's epidemic hotspot.

"The pandemic has changed me forever, it has made me more humane," the 41-year-old doctor tells AFP.

Since the first coronavirus case was reported in Colombia in March 2020, more than 50,000 healthcare workers in the country have been infected, and 227 have died.

Colombia is one of the top 11 countries in the world in terms of infections.

More than 2.3 million people in the country of 50 million inhabitants are recorded to have contracted the virus, resulting in over 61,300 deaths.

For many months during 2020's first, terrible epidemic wave, Medina formed part of a team of more than 60 doctors at his unit who took turns in three daily shifts to take care of the most severely ill.

In the worst periods, the few doctors not infected had to double their shifts to make up for the absence of their fallen colleagues.

It was a time that took a heavy toll on doctors' states of mind, and their personal lives.

"No matter how hard you tried for the patients, how hard you tried to keep them alive, they developed complications and died," recalls Medina.

The next blow: Medina and his wife, 34-year-old emergency doctor Mayely Silva, made the difficult decision last June to distance themselves from their children, aged one, eight and 10, for the youngsters' own safety.

The kids stayed with their grandparents as the medical pair battled the virus in the front lines.

"There were times when I couldn't (work) anymore, I didn't want to work anymore," Medina says.

Shortly afterwards, the virus exacted another heavy price, infecting Medina and his wife.

Silva experienced mild symptoms, but Medina fell gravely ill after fighting the infection for 11 days, with trouble breathing and a fever.

He has a history of asthma.

"One morning I awoke and told my wife: 'I can't take it anymore'," he recounts.

Medina drove himself to the nearest hospital and was diagnosed with coronavirus-related pneumonia. He was admitted to the ICU immediately.

"When I received this news I abandoned the role of doctor and adopted the role of patient," he says.

Remembering the many patients who had died under his care, Medina was well aware of the uphill battle awaiting him.

"There were moments of total uncertainty and absolute fear... Feeling death's presence was a new experience, but also very traumatizing," the doctor says.

As a patient, he remembers the ICU as a noisy place, with life support machine "beeps here, nurses shouting there, doctors running."

As his condition worsened still, and with just enough breath left to speak, he phoned his family to speak frankly about "the possibility of death".

Doctors wanted to put Medina on a ventilator, but he refused the invasive procedure he knew had been unable to save many of his own patients.

For his wife, this was a time of sad and sober reflection.

"My husband is the rock of the family, and to say that it is now up to me to carry the burden... was a difficult role change," she recalls.

But Medina got better.

On day 15, he was discharged, though still feeling unwell. At home, his symptoms disappeared one by one over a matter of weeks.

By August, still battling for breath, he was back to helping others -- donating plasma that can be given to infected people to help their immune systems fight the virus.

And exactly 54 days after he was diagnosed, Medina returned to work, though left with an affliction of the thyroid he says has been getting better ever since.

Medina, who already knew at age 10 that he wanted to be a doctor, carries out his work with the same zeal as always, but with more empathy for the pain and loneliness of ICU patients, he says.

He has since received two shots of a coronavirus vaccine, which he says has made him feel "more relaxed".

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, even people who have had Covid-19 should get vaccinated, as it is not known how long post-recovery immunity lasts.

"The vaccine for me represents a great achievement, a hope... it is the reward for all the work and effort," says Medina.

He tells AFP the pandemic has robbed him of several colleagues, but not his commitment to healing.

While case numbers have been decreasing, and there are available beds in his ICU, Medina knows that waves come and go.

"There will always be the fear... the uncertainty of knowing whether at some point one is going to get infected again," he says, before returning to his patients.

"I was born for this. It is my vocation," he shrugs.

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.