The Internet Is Killing Bookstores -- In China Too

In China, as in the rest of the world, increasing numbers of people are purchasing books online or in e-book format for their handheld devices. Many bookstores have become vestigial attachments to cafes and fast-food restaurants, and the physical spaces of Internet booksellers such as Amazon China, Dangdang.com and used-book retailer kongfz.com tend to be wedged into corners.

Facing an end that seems all but inevitable, bookstores have turned to more creative methods to promote themselves. The famed Harvard Book Store in Boston, with its nearly 80 years of history and after 20 years of cutthroat competition from Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN), now has a sign that says, “If you see it here, buy it here, keep us here.” A desperate last plea. Bookstores in China are doing the same.

Hong Kong’s “Second Floor Bookstores”

“Second Floor Bookstores” refers to the bookstores that have had to retreat to the second floors of the shops on Nathan Road, the busy main thoroughfare in Kowloon, Hong Kong, due to rising first-floor rents. They have become a part of Hong Kong’s literary culture.

Their retreat looks, at first glance, to be a forced choice, but it is in fact a wise decision that aids significantly in their survival. Even though these stores lose a certain amount of foot traffic, a large part of that is people who wander in to rest and rarely purchase books.

Bookstores’ loyal customers, however, are willing to climb to the second floor. “Going to a physical bookstore has become a separate hobby,” an economics professor from The Chinese University of Hong Kong said. “I know the store owners. When they email to say new books are here, I’m willing to visit to see if there is anything I want to purchase, despite having to climb stairs.”

Many of these booksellers are also using social media, such as Douban (a website that allows users to create content related to entertainment and culture), Renren (the Chinese equivalent of Facebook) and Weibo (China’s Twitter), to advertise.

A Rare Success Story

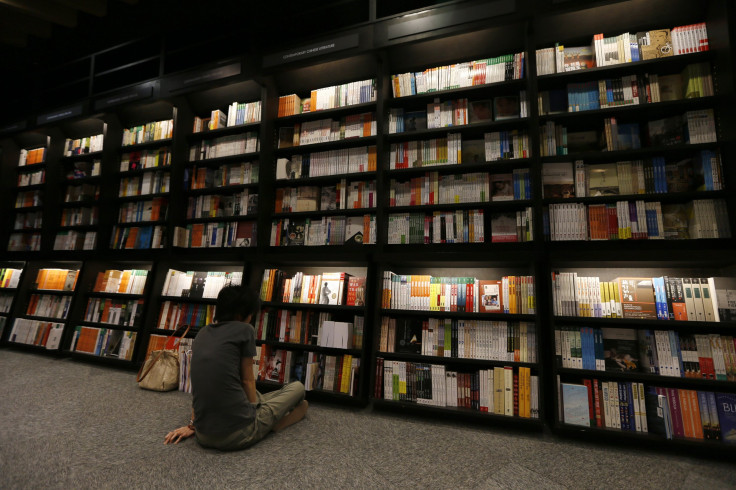

In mainland China, Fangsuo Bookstore in Guangzhou is a rare example of success. An inscription on its doors, quoting the Hong Kong poet Ye Si, says, “I wish we could return to an age when people read poetry out loud, so that the harmony in the wind may carry more hidden meanings that we must listen to carefully.” Harmony can indeed be used to describe the store’s inventories: It carries a variety of books about humanities, arts, design and architecture, with nearly 40,000 books from Hong Kong and foreign-language books, along with some that were published in mainland China. They also sell, entirely as an independent retailer, picture books, clothes, plants, coffee and other consumer products.

This way, books and other products can become mutually supportive. Customers who want to browse the clothing selections can also rest with a cup of coffee and read a few books. Many books at Fangsuo are rare editions not found on the Internet, which draws in many book collectors.

Store Branding Is Key

The Eslite Bookstore chain in Taiwan was established in 1989 by Wu Qingyou, a well-respected Taiwanese historian and author. His guiding vision is for bookstores to become places to experience culture rather than just buy books, making them irreplaceable by Internet booksellers. Eslite, now boasting 48 branches, has become part of the Taiwanese tourism industry. Many young tourists visit the store during their travels and often purchase a few books as gifts.

Eslite has become its own defiant brand, pursuing a mission to "sell the best books in the best locations, because culture cannot be discounted or cheapened."

The original story appeared in IBTimes China.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.