An Investor's Guide To Midstream Oil And Gas

The midstream sector is one of the three links in the oil and gas value chain, which encompasses companies that work together to help a market operate efficiently. In energy, the value chain takes hydrocarbons produced at the wellhead (upstream) and moves them (midstream) to end users (downstream). Activities in the midstream industry include transportation, processing, storing, and marketing hydrocarbons such as natural gas, oil, and natural gas liquids (NGLs). Each one of these energy commodities has its own linked set of midstream assets designed to maximize the value of every barrel that comes out of the ground.

This article originally appeared in The Motley Fool.

The midstream sector is an important one not only to support the infrastructure needs of the oil and gas industry but also for investors. Midstream stocks leverage their crucial role in the energy sector to produce lots of cash flow, which affords them the ability to pay high-yielding dividends. That's why income-seeking investors will want to get to know this important sector.

The midstream oil and gas sector 101

The midstream sector serves a vital role in the oil and gas industry by helping transport and transform raw hydrocarbons produced by a well into usable materials for refineries and petrochemical plants. The midstream sector has three main components: gathering and processing, transportation, and storage and logistics.

It all starts upstream at a wellhead. After drilling a well, an oil and gas company (or a third party) will often construct a pipeline that will gather the raw hydrocarbons produced from that well and others. The raw hydrocarbons will then flow into a central facility that will store, process, and separate the various hydrocarbons. Then, the processed liquids will flow further downstream by pipeline, truck, tanker, and rail for additional storage and processing before ultimately reaching their downstream destination.

Several types of companies operate in the midstream sector: integrated oil companies, sponsored midstream companies, and independent midstream companies. Integrated oil companies operate across the entire energy market value stream -- including the midstream sector -- so that they can maximize the value of every barrel they produce. In addition to integrated oil companies, there are also two types of "pure-play" midstream companies. Some oil and gas producers have created separate, publicly traded midstream companies that operate across the midstream value chain, serving the needs of the parent company, as well as those of third-party customers. Meanwhile, independent midstream-focused companies fill in the gaps by providing services to oil and gas producers that need access to midstream assets.

What are the steps in the midstream oil and gas value chains?

The output from a well flows across three distinct midstream value chains: one each for oil, natural gas, and NGLs ( click here for an interactive infographic -- requires Flash). Oil, a mixture of natural gas and NGLs, and water flow out of a producing well and into a gas-oil separation package. That component separates the oil and water from the natural gas/NGL mixture. Midstream companies then either pump the water into a disposal well or recycle it, while the oil, natural gas, and NGLs flow down their respective value chains.

The oil value chain starts with crude oil flowing into gathering tanks. It then moves by tanker, truck, or gathering pipeline to an offsite storage and blending facility. From there, a pipeline, truck, rail, or tanker will transport the crude oil to a larger storage hub, such as the United States' main hub in Cushing, Oklahoma, until it's transported to a storage tank at a refinery while awaiting processing. After they're refined, those products move again by tanker, truck, or pipeline to end users such as gas stations.

Similarly, natural gas and NGLs flow together from the wellhead through gathering pipelines to a processing facility that separates methane gas from the NGL stream. From there, the natural gas and raw NGLs part ways and head down their respective value chains.

Natural gas flows through transportation pipelines to natural gas storage facilities, which are usually located in underground salt caverns or depleted gas wells. When needed, it will either flow into a natural gas distribution system that sends it to end users such as homes and businesses or to a liquefied natural gas (LNG) facility so that it can be liquefied and transported to overseas markets.

NGLs, meanwhile, go from a processing facility to a fractionation complex, which then separates them into various products such as ethane, butane, propane, and natural gasoline. Those liquids then move by pipeline or truck to storage facilities before heading to end users such as petrochemical complexes, your backyard grill, or an export terminal.

How midstream companies make money

Midstream companies have an opportunity to make money along each link of the oil, gas, and NGL value chains, earning revenue via three primary means: fees, regulated tariffs, and commodity-based margins. Each part of the chain tends to use a preferred revenue-generating structure.

Gathering pipelines, for example, tend to be fee-based. Oil and gas producers will sign a long-term contract with a midstream company, either one they control or a third party, that will then build out a gathering system to support future wells. The producer will then pay a fee on every barrel that flows through the system, similar to a driver paying a toll to go over a bridge. Storage facilities also tend to charge fees for space, much like metered parking or a public garage.

Longer-haul pipelines that cross state lines, known as interstate pipelines, tend to earn regulated tariffs, which are fees determined by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in the U.S., to ensure pipeline companies don't use their monopoly power over specified pipeline routes to overcharge for their services. In many ways, the country's interstate pipeline system is much like a toll road, since the pipelines collect more tariffs the farther the oil and gas travels down the network.

Finally, a midstream company makes a commodity-based margin when it earns revenue based on the difference between the price of a raw commodity and a more refined product. That happens when a midstream company buys the natural gas and the NGL mixture from a producer and then separates it into the various NGL components like ethane and propane, which it then sells for a higher value. Processing and fractionation facilities, for example, often charge margin-based fees. While midstream companies that operate assets under a commodity-based margin structure can make more money during periods of high commodity prices, their cash flow is much more volatile than the cash flow of companies focused on owning assets backed by fee-based contracts or regulated tariffs.

Understanding the different types of midstream stocks

Midstream companies come in all shapes and sizes. Some midstream companies own only gathering and processing assets supported by their oil and gas producing parent, or focus on a specific commodity or part of the midstream chain. Others operate across the entire value chain.

Midstream companies can also have different structures for tax purposes. Some have chosen to be a master limited partnership (MLP), an entity that doesn't pay income taxes at the corporate level. In exchange, MLPs must distribute 90% of their taxable earnings to their partners, who pay personal income taxes on those earnings. Other midstream companies choose a traditional C-Corp structure, the same as most publicly traded businesses. That means those companies pay income taxes at the corporate level while their investors also pay income taxes on the dividends received.

It's important for investors to know a midstream company's structure because MLPs have some drawbacks. Most retirement accounts don't allow MLPs because investors receive a Schedule K-1 to file with their taxes instead of a 1099 form, which can complicate income tax reporting. That's why investors need to fully understand the implications of owning an MLP before adding any to their portfolios.

The 10 largest midstream oil and gas companies

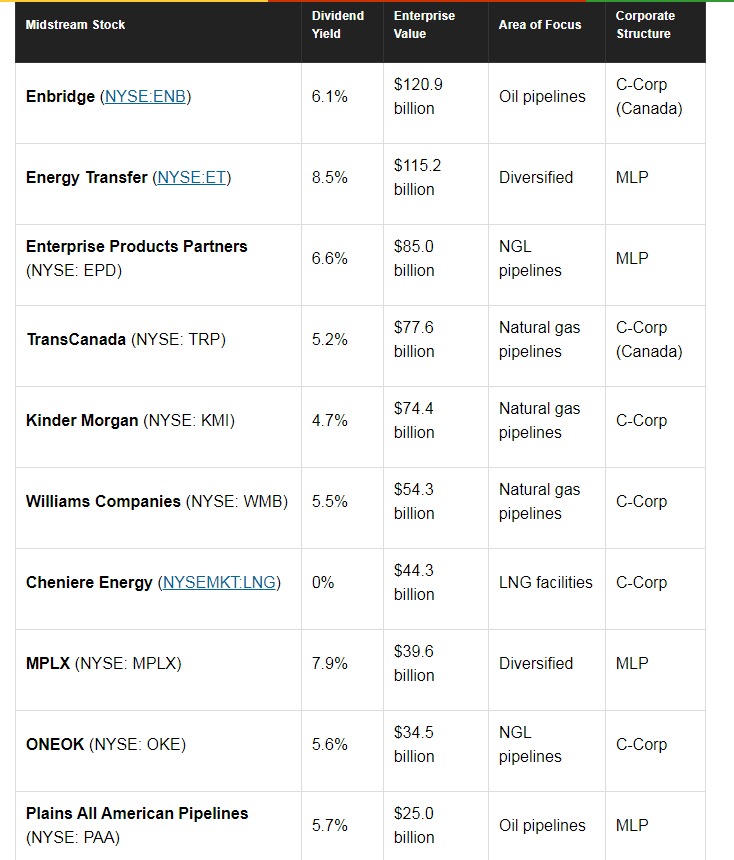

There are currently around 70 publicly traded midstream-focused oil and gas companies operating across North America. The 10 largest by enterprise value are listed below:

As the table shows, most of the companies on this list pay outsize dividends, which is why income-seeking investors tend to flock to the midstream sector. However, it's important for investors to drill down a lot further than just a midstream company's yield before buying. Here's an in-depth look at three names from that list to give investors some insight into how to analyze the sector.

Enbridge: The largest energy midstream company in North America

Enbridge operates the world's longest and most sophisticated oil and liquids transportation network with more than 17,000 miles of pipelines. Its main system moves an average of 2.9 million barrels of oil per day, transporting 28% of all crude oil produced in North America.

In addition, Enbridge is a leader in transporting, gathering, processing, and storing natural gas. It moves 22% of all gas used in North America through 65,800 miles of gathering lines, 25,500 miles of longer-haul transmission lines, and 101,700 miles of distribution pipes connected to 3.7 million customers in Canada and New York State, making it a true end-to-end network.

Enbridge makes most of its money transporting oil and liquids, with 50% of its earnings coming from that segment in 2017, though that's down from more than 75% in 2015 due to the company's recent acquisition of gas-focused Spectra Energy. Gas transmission and midstream services make up roughly 30% of its earnings, while its power and gas utilities businesses contribute the rest. Because the bulk of Enbridge's assets are pipelines or other utility-like assets, fee-based agreements and regulated tariffs supply the company with 96% of its cash flow, giving it a very stable and predictable revenue stream.

The company's ability to generate such steady cash flow gives it the funds to pay a lucrative dividend as well as invest in growth projects. Currently, Enbridge expects to invest 22 billion Canadian dollars ($17.2 billion) in expansions through 2020, which should grow its earnings at a 10% compound annual growth rate, fueling a similar growth rate in its dividend. That ability to increase its high-yielding payout at a high rate positions Enbridge to deliver market-beating returns in the coming years.

Energy Transfer: A diversified midstream behemoth

Energy Transfer is undergoing an important transformation. The company recently completed the acquisition of its MLP Energy Transfer Partners in a deal that will give it full control of the assets and cash flow generated by that entity. In addition, it controls two other MLPs, USA Compression Partners ( NYSE:USAC) and Sunoco (NYSE:SUN), which entitles it to a portion of their cash flow.

Following the Energy Transfer Partners merger, the new Energy Transfer is a fully integrated midstream company with assets spanning the entire value chain. The company's natural gas gathering and processing business consists of 33,000 miles of pipeline, as well as significant processing capacity, including both commodity-based and fee-based assets. From there, gas will travel across one of the largest intrastate and interstate pipeline networks in the U.S., where fee-based contracts support 95% of the company's revenue. Meanwhile, Energy Transfer also has a world-class NGL platform that processes, transports, fractionates, stores, and exports NGLs, as well as a large-scale crude oil business, including long-haul pipelines, storage facilities, and an export terminal. Finally, the company's investment in Sunoco LP gives it a stake in one of the largest fuel distribution businesses in the U.S., while USA Compression Partners, one of the largest gas compression companies in the country, enables midstream companies to move more gas through pipelines. Overall, fee-based contracts or regulated tariffs support roughly 90% of Energy Transfer's revenue stream.

Energy Transfer expects to generate $2.5 billion to $3 billion of excess cash flow per year after paying its high-yielding distribution. That will give the company a significant portion of the funding needed to support its large-scale expansion program. The company has a long list of midstream assets under construction, including an important oil pipeline out of the fast-growing Permian Basin, an expansion of a major NGL pipeline, and a terminal to export ethane. In addition, the company is working on a large-scale LNG export facility along the Gulf Coast. These expansion projects should provide the company with the fuel to increase its lucrative payout in the coming years.

Cheniere Energy: A pure play on LNG exports

Cheniere Energy is the leading producer of LNG in the U.S. and has enough capacity under construction to become a top-five global producer by 2020. The company currently has two LNG facilities under development along the Gulf Coast: Sabine Pass and Corpus Christi.

Sabine Pass started operations in 2016, enabling Cheniere to become the first company ever to export LNG from the lower 48 states. The company currently operates four liquefaction units, or trains, which perform a refrigeration process that drops the temperature of natural gas down to minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit, at which point it becomes a liquid, and its volume shrinks 600 times. Cheniere is then able to load the LNG into gas carriers so it can be moved by sea to LNG import facilities in foreign countries. From there, the LNG undergoes a regasification process so that it can flow through pipeline systems to its final destination.

Cheniere Energy currently has one more LNG train at Sabine Pass under construction that should be operational in 2019, and a sixth one under development. It also has two at Corpus Christi under construction that should also start operations next year, and it recently started construction of a third train at that site. Cheniere also owns enough land at both locations to continue building new trains that could double its capacity to produce LNG in the future.

Cheniere Energy makes most of its money by locking in a fee-based margin under long-term contracts. The company purchases natural gas on the market; pipelines transport the product to its facilities, including ones it owns as well as those operated by third parties such Kinder Morganand Williams Companies, which built them specifically for that purpose. The company then charges customers a fee to liquefy the gas, with 85% to 95% of its anticipated production locked in by long-term contracts. The cash flow from those fees gives Cheniere some of the money needed to continue expanding its LNG empire. The company eventually expects to pay a dividend to its investors with some of the cash flow from its LNG business.

The future of midstream oil and gas

As big as the North American midstream oil and gas sector is today, it will become even larger in the coming years. The Interstate Natural Gas Association of America Foundation estimates that midstream companies will need to invest nearly $800 billion through 2035, or $44 billion per year, in building oil, natural gas, and NGL midstream assets needed to meet the industry's needs.

More than half of that investment, or an estimated $417 billion, will be in building new natural gas midstream infrastructure, including gathering and transmission pipelines, processing plants, storage capacity, and LNG export facilities. The industry also needs to invest another $321 billion in new oil infrastructure, including gathering and long-haul pipelines, storage tanks, and export docks. Finally, midstream companies will need to invest an estimated $53 billion in new NGL-related infrastructure such as pipelines, fractionation capacity, and export facilities. This forecast suggests that midstream companies will be busy expanding their footprints over the next two decades. That growth has the potential to enable midstream companies to create significant value for investors as they increase their high-yielding dividends.

Why investing in midstream stocks could make sense in your portfolio

Two factors should make the midstream sector attractive to investors. First, midstream companies tend to generate lots of cash flow because fee-based contracts or regulated tariffs supply them with the bulk of their income. That makes them less volatile than other energy stocks and gives them the cash needed to pay some of the highest-yielding dividends in the market.

The sector also offers ample growth in light of the projected need for new midstream assets in North America. As midstream companies build these assets, they should boost their cash flows, giving them more money to pay dividends. That growing income stream could provide many midstream stocks with the fuel they need to outperform the market in the coming years.

Matthew DiLallo owns shares of Enbridge, Enterprise Products Partners, and Kinder Morgan. The Motley Fool owns shares of and recommends Kinder Morgan. The Motley Fool recommends Enbridge, Enterprise Products Partners, and ONEOK. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.