Iran Starts Counting Votes After Elections

Iran started counting tens of millions of votes on Saturday after hotly contested elections that could see reformists speed up Tehran's opening to the world or long-dominant hardliners reassert the Islamic Republic's traditional anti-Westernism.

The twinned elections for parliament and a leadership body called the Assembly of Experts are seen by some analysts as a potential turning point that could shape the future for the next generation, in a country where nearly 60 percent of the 80 million population is under 30.

The elections are the first since Tehran agreed with major powers to curb its nuclear program, leading to the removal of most of the stringent international sanctions that have paralyzed the economy over the past decade.

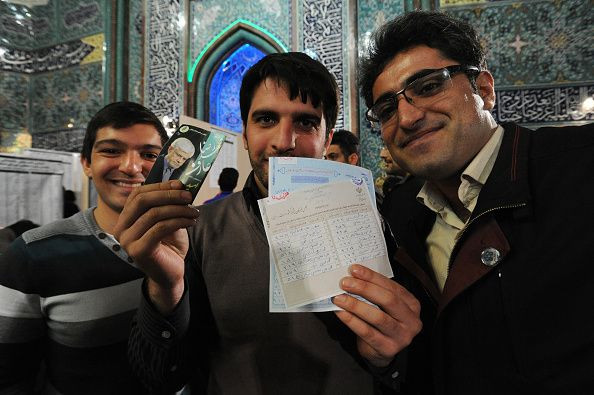

Turnout was heavy. Polling was extended five times for a total of almost six hours, because so many people wanted to vote.

First partial results are not expected until Saturday, and a clear outcome may take days to emerge, although conservatives normally perform well in rural areas and young urbanites are seen as favoring more moderate candidates allied to President Hassan Rouhani.

Supporters of Rouhani, who championed the nuclear deal, are pitted against hardliners close to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khameni. They are deeply suspicious of detente with Western countries, seen as adversaries implacably opposed to the 1979 revolution that toppled the Shah.

MOUSAVI VOTES

Authorities had promised that all Iranian would be able to vote, and on Friday opposition leader Mir Hossein Mousavi and his wife voted for the first time since being put under house arrest in 2011, an ally of Mousavi's told Reuters.

Among other voters at a polling station in Khorasan square, a working-class neighborhood in Tehran, Mahnaz Mehri, a 52-year-old mother of four, said she was voting for reformists because they had a better vision for the economy and foreign policy.

In Meydan Beheshti square, a mainly conservative neighborhood, Reza Ganjialilu, a 28-year-old employee at an electronics shop, said he did not favor the reformists.

“I have a duty to my country. This group of people (conservatives) are the best. Our main concern is preserving our religion, ideology, not just the economy,” he said.

Iran, which has the world's second largest gas reserves, a diversified manufacturing base and an educated workforce, is seen by global investors as a huge emerging market opportunity, in everything from cars to airplanes and railways to retail.

For ordinary Iranians, the prospect of this kind of investment holds out the promise of a return to economic growth, better living standards and more jobs in the long run.

An opening to the world of this scale — and Rouhani's popularity — have alarmed hardline allies of Khamenei, who fear losing control of the pace of change, as well as inroads into the lucrative economic interests they built up under sanctions.

BUSY POLLING

Both camps appeared successful in getting supporters out to vote. Although extensions of voting are common in Iranian elections, many were surprised to see polling as busy in the evening as it had been in the morning. State television said voting booths in other cities were still packed mid-evening.

Influential former president Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, allied to Rouhani, called on election authorities to protect people's votes. “You should show our people that their votes will be preserved and are in safe hands,” he said.

Asked what would happen if reformists did not win, he told Reuters: “It will be a major loss for the Iranian nation.”

Rouhani wants to cash in on the popularity he gained from the nuclear deal to help his supporters wrest parliament from the hardliners who control it and possibly help him win a second presidential term in elections next year.

Although Iran's foreign policy is dictated by Khamenei, the outgoing conservative-dominated parliament strongly opposed making any meaningful concessions to the West during the nuclear negotiations and some lawmakers called Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif a “a traitor.”

At stake is control of the 290-seat parliament and the 88-member Assembly of Experts, the body that has the power to appoint and dismiss the supreme leader. Like the parliament, the assembly is in the hands of hardliners.

During its next eight-year term it could name the successor to Khamenei, who is 76 and has been in power since 1989.

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.