For Iranian Regime, Tehran Bazaar Protest Could Be A Game-Changer

Opinion

Bazaaries, the Farsi name for Iran’s traditional merchants, are typically a conservative, wealthy bunch reluctant to involve themselves in politics. But their displeasure with President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who they believe is responsible for bungling the economy, has changed that.

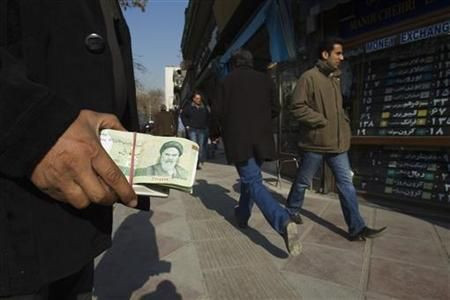

On Oct. 2, in a unique confrontation between the Bazaaries and the government, the merchants closed the Bazaar and protested against Ahmadinejad, the government, and, more specifically, the sharp decline of Iran’s currency. This time last year, the U.S. dollar bought 11,500 rials; now, a dollar is worth 39,500 rials -- a 70 percent increase.

Perhaps the most notable aspect of the Bazaaries’ decision to shed their apolitical posture is that historically when Iranian merchants protest against government activities, revolutions quickly follow. That’s not good news for the present Iranian administration.

The last time the merchants from Iran’s Grand Bazaar entered the political fray, the 1979 Iranian Islamic Revolution ensued. And the time before that, the 1905-1907 Constitutional Revolution was the outcome.

“Bazaaries don’t like an unsteady situation or a sudden change in Iran because it is bad for their business,” Iranian journalist and political expert Roozbeh Mirebrahimi said. “It interrupts normal life routines.”

Indeed, during the 2009 protests, known as the Green Movement, that attempted to topple the newly reelected Ahmadinejad regime, the Bazzaries stood on the sidelines because there seemed to be little economic gain to what the anti-administration advocates were offering.

“But now, their wealth, the reason that kept them away from protests, is in jeopardy,” Mirebrahimi added.

BBC News reported from the Iranian-Turkish border that, usually, in good economic times, queues of trucks would be waiting at the border to enter Iran. But now the trucks have stopped coming. It’s obvious from this that the Iranian economy is barely afloat and the Bazzaries’ business is taking the hit.

Bazaaries still have the capital to purchase new products but are struggling to determine a fair selling price due to the falling value of the rial. In addition, inflation decreases the average citizen’s buying power, further restricting the Bazaaries’ profits.

“Economic problems in Iran can unite many people for protest because not everyone in Iran is looking for freedom and democracy, but everyone is worried to fill their shopping cart,” said Arash Hasannia, an economics reporter for Radio Farda.

Of course, national and international events can increase or decrease the dollar’s value, but the drastic fall of the rial came just one day after the United States issued sanctions against Iran this summer -- a move quickly mimicked by the European Union.

According to Hasannia, the double-sanction whammy reduced the supply of dollars in Iran while encouraging investors who were concerned about Iran’s economic prospects to sell the rial and purchase more dollars. As a result, the rial plunged.

Naturally, the people held the president responsible for this economic downturn; he, naturally, refused responsibility and defended his economic record a day before the strikes occurred in the Tehran Bazaar. Instead of taking ownership, Ahmadinejad alleged that foreign trade doesn’t have a very high value in the Iranian economy and that “figures are being used in a psychological war for a greater effect in the market.” He also added that “enemies have managed to reduce our oil sales, but hopefully we will compensate for this.”

These kinds of comments do little to curry support from the Bazaaries, who are more inclined to back the Motalefe, a conservative political party opposed to many of Ahmadinejad’s stances, including his attempt in the last presidential campaign to downgrade wealth in order to gain poor and middle class votes. In 2005, the Bazaaries supported Motalefe’s Ali Larijani, the current head of Iran’s parliament, for the presidency.

The Motalefe and Baazaries are convinced that Ahmadinejad’s flawed economic judgment and his hardline stance on Iran’s nuclear program is responsible for Iran’s weak economy.

“The truth is that Iran’s economic problems -- sanctions included -- are not going anywhere until Iran decides to solve its relationship with the West, especially on the nuclear program and de-radicalize the political stands in Iran,” Radio Farda’s Hasannia said.

Speaking beside Kazakhstan’s foreign minister on Oct. 10, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said the sanctions could be removed quickly if Iran’s government complies with the West’s calls to halt its nuclear weapons development and uranium enrichment program, which Iran maintains are for peaceful energy purposes.

Nonetheless, Ahmadinejad isn’t the Bazaaries’ only obstacle: the vast power of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei also makes it impossible to rectify the situation. Even if the Bazaaries and their allies convince parliament to remove Ahmadinejad from power because his economic stewardship has been so dismal, Khamenei’s approval would be needed. And he has already thrown his support behind Ahmadinejad.

Iran’s regime might decide to cooperate with Western powers opposing its nuclear program, resulting in the removal of some sanctions. But that’s unlikely, which means that the next six months until Iran’s presidential election will be a pivotal time for the country’s political and economic system.

It’s a period that will determine whether a revolution is afoot -- thanks in large part to the Bazaaries -- that will lead to the end of the Islamic regime in Iran, or whether the country will continue on its path toward a radical and isolated North Korea-like era.

For more than 12 years, Solmaz Sharif has worked as a journalist for Persian media outlets such as BBC Persian and the Etemad Melli Newspaper. She is also founder of the first Iranian women's sports magazine, Shirzanan. She writes for Movements.org. Her web site is: www.solmazsharifdj.com

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.