Jailed Chadian Ex-leader Hissene Habre Dies In Senegal

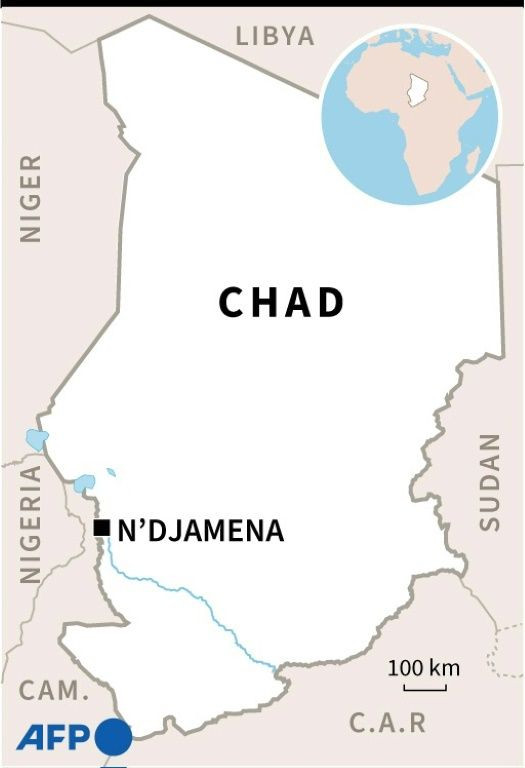

Former Chadian president Hissene Habre, who was serving a life term in Senegal for crimes against humanity, died from Covid-19 on Tuesday aged 79.

Chad's consulate told AFP that the former dictator had succumbed to coronavirus in Dakar's main hospital, where he had been rushed from a private clinic after his condition worsened.

"Habre is in his Lord's hands," Senegal's Justice Minister Malick Sall said on the television channel TFM, announcing Habre's death.

The head of Chad's ruling military junta, Mahamat Idriss Deby Itno, also offered his "sincere condolences" to Habre's family "and the Chadian people."

"To God we belong and to Him we return," Deby said on Twitter.

Habre seized power in 1982, ruling with an iron fist until he fled to Senegal in 1990 after being ousted by Deby's father, Idriss Deby Itno, who died fighting rebels earlier this year.

Habre's rule was marked by brutal crackdowns on dissent, including alleged torture and executions of opponents.

Some 40,000 people are estimated to have been killed, earning Habre the nickname of "Africa's Pinochet."

In exile in the Senegalese capital Dakar, the former leader lived a quiet life in an upmarket suburb with his family.

But he was eventually arrested in 2013 and tried by a special tribunal set up by the African Union (AU) under a deal with Senegal.

The trial created legal and political precedent, marking the first time that a country prosecuted a former leader of another nation for rights abuses.

In May 2016, Habre was handed a life term for war crimes, crimes against humanity and torture. The sentence was upheld the following year.

As Habre began serving his sentence in the Cap Manuel penitentiary in Dakar, his supporters voiced concern for his health and pushed for more lenient conditions given his advanced age.

Last year, a Senegalese judge granted him a two-month furlough designed to shield him from coronavirus.

Groups representing Habre's victims recognised his right to be treated humanely, but fiercely resisted preferential treatment for the former dictator.

Reed Brody, a lawyer who represented Habre's victims, was withering about Habre's legacy on Tuesday, saying in a statement that he would "go down in history as one of the world's most pitiless dictators."

Habre "slaughtered his own people to seize and maintain power... burned down entire villages, sent women to serve as sexual slaves for his troops and built clandestine dungeons to inflict torture on his enemies," Brody said.

The ex-dictator's nephew Kelley Chidi Djorkodei, who was at the hospital in Dakar, told AFP he blamed the Senegalese government for Habre's death.

"The Senegalese state could have avoided this, just by releasing him," he said.

But justice minister Sall rejected the criticism.

Habre had been ill and had been transferred to a "top-of-the-line private clinic" in Dakar at his family's request, he said.

"It was in this clinic that he caught Covid," the minister said, adding that President Macky Sall then asked for Habre to be transferred to Dakar's main hospital, which was where he died.

"We should all be proud of the way we welcomed Habre," he said.

Sall added that the prison authorities had been preparing to fit an electronic bracelet on Habre, suggesting he could have served his sentence in his home in Dakar.

Habre's conviction was seen as a turning point for pursuing rights abusers in Africa, where the International Criminal Court (ICC), located in The Hague, was becoming increasingly unpopular.

The former dictator was ordered to pay up to 30,000 euros ($33,000) to each victim who suffered rape, arbitrary detention and imprisonment during his rule, as well as to their relatives.

Victims' groups say they have not been paid, however, and they suspect that Habre has left behind a considerable fortune.

Jacqueline Moudeina, another lawyer representing Habre victims, told AFP that "this death does not absolve Chad or the African Union from compensating the victims".

Abdourahmane Gueye, a Senegalese Habre victim who once sold jewellery in Chad, said: "We have no grudge against him".

"We just need to put pressure on the African Union so that the victims are compensated," he added.

Chad's government has said that it would not oppose Habre's body returning to home, it would not commemorate the former leader's death out of respect for his victims.

But Fatime Raymonne Habre, the ex-dictator's wife, said in a statement Tuesday that her husband will be buried in Senegal until the day when he "will be fully rehabilitated, and that all that he has done for (Chad) will be recognised".

Despite his bloody reputation, some in Chad continue to view Habre in a positive light, as a stern-willed patriot who sought to strengthen his young state.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.