Janet Yellen's Dashboard: 3 Data Points That Will Guide The Federal Reserve's Interest Rate Decision

U.S. Federal Reserve Board Chairwoman Janet Yellen faces a daunting task this week as policymakers debate whether to raise interest rates for the first time in nearly a decade. The Fed's decision hinges on whether central bankers agree that the U.S. economy is on course for hitting major objectives, low inflation, full employment and financial market stability.

Some experts argue Yellen will hold off on raising rates this week because they consider her to be a "dove," or someone who generally favors low interest rates. History, however, suggests otherwise, as she was one of the first to vote for an increase in interest rates in the 1990s when she served on the Federal Reserve's board of governors.

“She is not a dove,” Chris Faulkner-MacDonagh, a market strategist at Standard Life Investments, said. He noted that in the mid-1990s, “she was pressing Alan Greenspan to increase interest rates before the Fed eventually did.”

Yellen, who spent a good portion of her career in academia, is known for being a data-driven technocrat who lets the information guide her decisions on monetary policy. According to experts and economists, here are three most important data points Yellen will revisit this week to decide whether to hike rates for the first time since 2006.

1. JOLTs

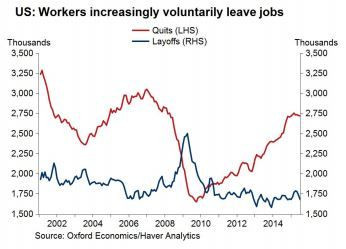

Yellen has flagged the so-called voluntary-quits rate -- found in the monthly Job Opening and Labor Turnover (JOLT) report -- as a key labor market measure. A higher quits rate indicates that more workers are quitting jobs and moving to better-paying positions.

The number remained unchanged at 1.9 percent in July, but the increase in the quits rate over the past few years is in line with expectations and directly corresponds to the decline in the unemployment rate.

“If you feel strong enough about the economy and your own resources, you can quit your jobs and find a better job, that’s a good sign for the economy and suggests there’s some wage pressure out there,” John Canally, chief economic strategist at LPL Financial, said.

The Fed has a “dual mandate” of achieving maximum employment and stabilizing U.S. inflation. The unemployment rate sank to 5.1 percent in August, meaning that the Fed has arguably already achieved the full employment part of its mission. If there is still any slack left in the labor market, July’s JOLT data, released last week, suggested it won’t be around for much longer. The job openings rate surged to a record 3.9 percent in July, putting it well above the peak reached during the prior economic cycle.

2. Employment Cost Index

While the labor market data supports a hike, inflation is moving in the wrong direction. The economic recovery still has not led to wage growth.

Yellen will revisit the employment cost index, a quarterly report from the U.S. Department of Labor that measures the growth of employee compensation, including wages and benefits, to gauge the overall health of wage growth.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the unemployment rate fell to a low-enough level that it sparked some wage inflation, yet that has changed in recent decades. In the early 2000s the U.S. unemployment rate hovered around 4 percent, but there still wasn’t much inflation.

“Today wages are set as much in Beijing as they are in Boston, but that wasn’t the case in the 1960s and 1970s," Canally said. "When you’re in that global environment, the mechanisms that worked in the past don’t work anymore.”

Fundamentally, Yellen has to decide whether signs of tightening in the labor market are producing a higher rate of inflation. “That would really be the real reason to move,” David Wessel, director of the Hutchins Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy at the Brookings Institution, said.

Inflation stands at about 1.5 percent, according to the Fed's preferred measure. But the central bank wants to be reasonably confident inflation will rise to 2 percent, and that hasn’t really happened. A lot of that has to do with tepid wage growth. “You need to have wage growth to have inflation stick, and we just haven had any, despite the progress on the jobs front,” Canally said.

The employment costs are concerning to the Fed because the index rose just 0.2 percent in the second quarter, missing expectations for a 0.6 percent increase, the Labor Department said in July. That was the smallest gain since the agency began tracking the index in 1982. The index had jumped 0.7 percent in the first quarter.

3. Financial Conditions Index

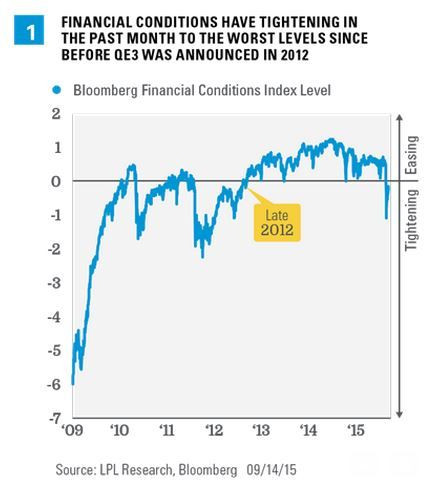

Most experts who argue that the Fed will hold off on raising rates this month point to the recent stock market volatility in August that saw all three of the U.S. major averages fall into correction territory amid fears that China, the world's second-largest economy, was slowing at a faster-than-expected pace.

The Fed will consider whether a rate hike would cause undue stresses in the financial market, leading to less bank lending, which would hurt the economy. The Fed usually refers to “financial stability” in its statements, and the way to ready that is through financial conditions index to see whether the recent volatility prevented any lending from happening by banks, or if companies have less access to credit. The gauge measures overall conditions in U.S. financial and credit markets, including the strength of the U.S. dollar and the relative strength of the U.S. money markets, bond markets and stock markets.

Arguing against a hike this week are financial conditions, as measured by the Bloomberg Financial Conditions Index, which have tightened considerably in the past month. Even after recovering in the past two weeks, financial conditions remain at their worst levels since before the Fed announced its third round of quantitative easing in September 2012.

“That probably doesn’t make the Fed very happy. They don’t want to tighten on top of the market already tightening,” Canally said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.