January 1973: A Divided Britain Joins Europe

On the first of January 1973, Britain joined the European Economic Community in festive spirits following a decade of tough negotiations, though public opinion on membership was mixed.

For around 10 days, as part of a "Fanfare for Europe" gala, 300 sports and cultural events were held nationwide showcasing the EEC countries.

Membership had increased from six to nine, with Denmark and Ireland also joining alongside Britain.

The Conservative government's europhile prime minister Edward Heath described Britain's entry to the bloc as "very moving".

Football players from the three new states played against a team of athletes from the six other countries. Italy loaned a Michaelangelo artwork for an exhibition, the Netherlands provided a Rembrandt. Only the Louvre declined to join the fun by refusing to let the "Mona Lisa" leave Paris.

Here is a look back at AFP's reporting from the time.

On December 31, 1972, the eve of the big day, the British press devote their front pages to the event. A chapter of a thousand years of history is closing, says The Sunday Times. The Sunday Telegraph predicts joining would prove as decisive for British history as the Battles of Hastings or Waterloo.

"The Daily Mail above all warns its readers against the use of inappropriate common parlance that could shock the citizens of the eight other countries," writes AFP.

Meanwhile the most passionate advocates against joining the EEC organise their last stand that day. Five hundred people join a torchlit procession to the sound of bagpipes in front of the Palace of Westminster, the seat of the British parliament.

Festivities get under way on January 2, 1973, at a "European" dinner with 258 attendees hosted by the British Council at Hampton Court Palace, the former royal residence.

The next day Heath, Queen Elizabeth II and her husband Prince Philip attend the first gala evening, an opera at Covent Garden in London, where they are met by stink bombs thrown by 200 protesters.

Public opinion is "hesitant and (...) remains -- polls say -- deeply divided" over joining, AFP reports. The decision to join had been taken in 1972 by a vote in parliament and it was never put to a referendum, unlike in Denmark and Ireland.

AFP reporter Basile Tesselin heads to a London pub to test the mood.

"We have our own government, a parliament we elect," a print worker tells him. "We do not want to be led by who knows what from Brussels. Everything we have is better than what you have."

"I'm wary of you, I see you coming," says a taxi driver from Scotland.

"You suck up to us, and then once we're in your sacred trap, your fool's paradise, you'll make us fall out with our real friends, the Americans, the Canadians, the Australians. And you'll all become communists and take us down with you."

The list of recriminations grows: fears that VAT (Value Added Tax) will increase, that the weight of trucks will become an issue, and over the free entry of Europeans.

"I like going to Europe," says one truck driver from Scotland. "Particularly to France. I feel at home there. I don't trust the English."

The opposition Labour Party quickly makes clear its intention to renegotiate the accession treaty. Its leader Harold Wilson accuses the government of having "abdicated" its responsibilities to Brussels.

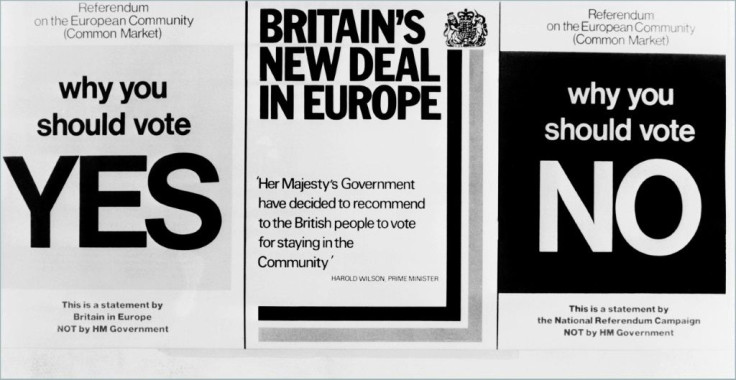

In 1974, Labour returns to power and, after securing a renegotiation, organises a referendum the following year on whether or not to remain in the EEC.

The "Yes" vote wins by 67 percent.

On June 23, 2016, 41 years later, Britons will vote by 52 percent to leave the now European Union.

Brexit plunges Britain into more than three years of crisis before its departure becomes reality on January 31, 2020.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.