Japanese Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): Japan Inc. Seeking Growth Abroad

Japanese companies are sitting on a record-sized cash pile -- some $2.4 trillion worth. But they’re reluctant to spend the money at home due to Japan’s slowly growing economy and declining population. Japan Inc.’s aggressive foray abroad has raised fears that the surge in foreign-direct investment is hollowing out the world’s third-largest economy.

“The fear is that offshoring of manufacturing will lead to a decline in investment and loss of employment opportunities at home,” Izumi Devalier, Japan economist at HSBC Holdings PLC (LON: HSBA), said in a note to clients.

Private companies’ cash and deposits rose 5.8 percent from a year before, to 225 trillion yen ($2.4 trillion) in the January-to-March period, according to Bank of Japan figures dating back to 1979. The $2.4 trillion equivalent compares with the $1.8 trillion in liquid assets held by nonfinancial U.S. firms, according to Federal Reserve data.

In Japan, cash and deposits represent more than half of total household financial assets, whereas the equivalent figure for the U.S. and Europe is 16 percent and 30 percent, respectively.

Demographics also help explain Japan's outward foreign-direct investment. One in four people in Japan will be older than 65 in 2014, compared with 9.6 percent in China and 14.2 percent in the U.S., according to data compiled by the U.S. Census Bureau. While deflation -- which has dogged Japan for two decades -- helps savers, younger generations without savings are hit by stagnant wages and diminished incentives for borrowing.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda are fighting to break Japan out of the liquidity trap. Japan’s central bank has promised to pump $1.3 trillion of liquidity into the economy over the next two years.

But “with domestic money demand still weak, and the long-term growth picture still cloudy, we believe it is highly likely that a significant part of this liquidity will make its way out of Japan,” Devalier said.

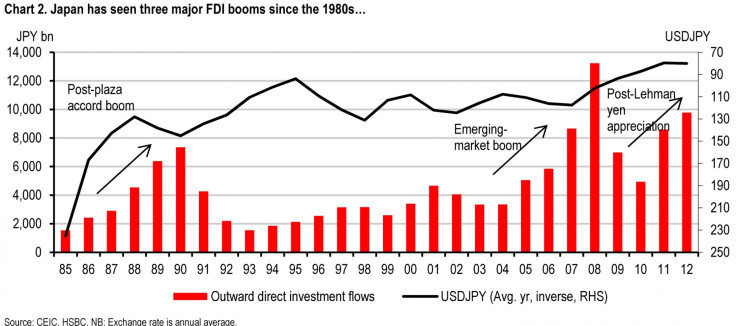

After a brief post-Lehman lull, Japan’s outward foreign-direct investment flows picked up again, hitting $122 billion in 2012.

The surge was driven by a record amount of merger and acquisition activity as Japanese corporations invested overseas to mitigate growth limitations in the domestic market. Record yen strength and an energy shortage back home have kicked the offshoring drive into high gear.

In recent years, Japanese companies have made a string of deals in the U.S., but the deal that has been hitting the headlines recently is one for the record books.

Softbank Corp. (TYO: 9984), the Japanese mobile network operator, is in the process of completing its acquisition of Sprint Nextel Corporation (NYSE: S). Earlier this week, Dish Network Corp. (Nasdaq: DISH) dropped out of the fight for the third-biggest U.S. wireless carrier and Softbank now hopes the deal will clear its final hurdles by the beginning of July. Once completed, it’ll mark the largest Japanese acquisition of a U.S. company in more than 30 years.

The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that if current mergers-and-acquisitions trends continue, “Japanese cross-border M&A activity will soon surpass its 1990 peak.”

According to HSBC, there have been three Japanese foreign-direct investment booms.

In the mid-1980s, Japanese corporates ramped up U.S. manufacturing bases in response to rising bilateral trade friction and a rapidly strengthening yen.

Then in the early 2000s, China ascended to the World Trade Organization, making it the factory of the world. Japanese firms quickly shifted low value-added, labor-intensive manufacturing to China to take advantage of cheap wages and economies of scale. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or Asean, economies with traditional links to Japan, such as Thailand and Indonesia, also benefited from the torrent of Japanese investment flowing into booming Asia.

More recently, foreign-direct investment outflows surged in 2011-2012. With the yen strengthening in the wake of the Lehman crisis, Japanese companies embarked on an M&A spending spree in developed markets. But investment into emerging Asia accelerated too, as companies continued to shift production abroad, especially as a domestic energy crisis eroded manufacturing competitiveness.

With Abenomics pushing the value of the yen down against the dollar to multiyear lows, some policymakers hope that a weaker currency will compel manufacturers to bring production back to Japan. But Devalier thinks a reversal is unlikely to happen any time soon. For one, wage differentials remain wide.

The average manufacturing wage in Thailand, which was the most expensive in developing Asia as of 2012, is still about one-tenth of Japan’s. Even accounting for differences in productivity, Asia is still a cheap place to do business.

China, which overtook Japan as the world’s second-largest economy three years ago, has been the major recipient of foreign-direct investment in the developing world for 20 years. It has played a big part in China’s rise from poor rural backwater to wealthy economic powerhouse.

Japanese foreign-direct investment, however, is a one-way street. With little investment coming in, Japan has recorded sustained FDI outflows over the past three decades.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.