J.C. Penney (JCP) Shrinks Top Name Brands As Own Labels Take Center Stage

By Phil Wahba

PLANO, Texas (Reuters) - J.C. Penney Co. Inc. <jcp.n> is looking to the past to build its future.

After two years of declining sales, the department store chain is eliminating or trimming some high-profile brands introduced by former Chief Executive Officer Ron Johnson, including its own jcp menswear, Joe Freshclothes and some Martha Stewart-designed home furnishings.

"What we now need is to edit things out that didn't resonate sufficiently," CEO Mike Ullman told Reuters in an exclusive interview at Penney headquarters in Plano, Texas.

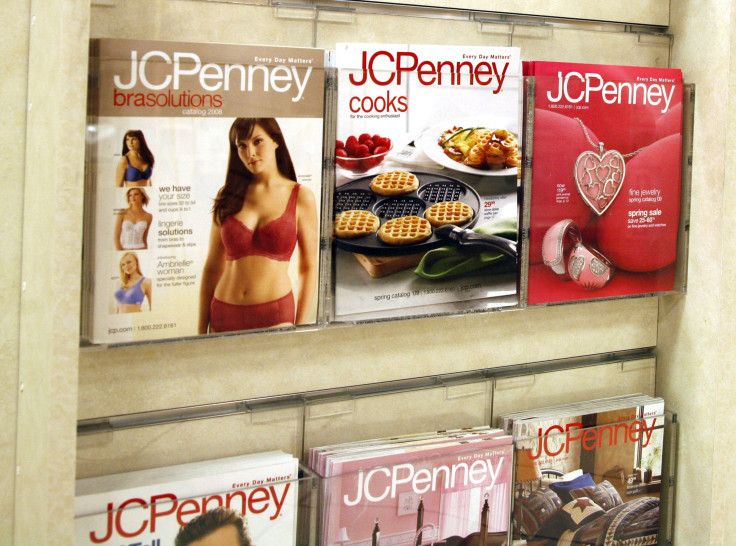

Penney plans to use the freed-up prime floor space for its more-profitable exclusive private-label brands. The retailer has brought back its billion-dollar St. John's Bay apparel line as well as JCP Home and Cooks, and it plans to reintroduce its Ambrielle lingerie in February.

The changes are the latest efforts by Ullman, 67, to rebuild the retailer, whose sales tumbled 25 percent after Johnson tried to make the stores more upscale and eliminated popular coupons and brands.

"He's trying to somehow rebuild a store that has an appeal to the core J.C. Penney customer," said veteran retail analyst Walter Loeb of Loeb Associates.

Ullman had led Penney between 2004 and 2011. When he returned in April, he immediately reinstated the discounts and brought back St. John's Bay to get longtime customers back in stores.

"The customer never gave up on the goods," he said. "We gave up on the customer, and we paid a price for it."

During Ullman's first stint as CEO, Penney's sales and gross profit margins reached all-time highs, and the company introduced the wildly successful Sephora cosmetics "shop-within-a-shop" that was the blueprint for Johnson's transformation plan.

But Penney's cost structure and sales per square foot lagged those of rivals, and the chain was seen by many as stagnant. In 2010, that attracted activist investor William Ackman, who pushed to replace Ullman with Apple Inc. <aapl.o> retail star Johnson the following year to transform Penney.

Johnson's strategy, which included dumping many Penney brands, cost the chain $4 billion in sales in 2012 and hurt gross profit margins. The lingering effects sent the stock to a 31-year low of $6.24 in October. It gained 0.6 percent to $8.53 in midday trading after declines earlier in the day.

Last quarter, gross profit was 29.5 percent of sales, about 8 percentage points below historical averages. This measure of merchandise profitability is about 5 percentage points higher for private brands because stores do not have to share profits with vendors and can control when items go on sale.

PRIVATE-LABEL PUSH

Increasing sales levels is the top priority, so Penney is also trying to get more out of its existing private brands by expanding them. For instance, it is looking into adding sportswear to its J. Ferrar line of men's suits.

It will launch a line of home goods, including towels and bedding, under its Liz Claiborne brand to replace the Martha Stewart-designed "jcp Everyday" items that were supposed to bear her name. That collection is at the heart of ongoing litigation brought in 2012 by Macy's Inc. <m.n>, which claimed exclusive rights to certain Martha Stewart home goods.

Penney continues to sell Martha Stewart products in categories like dry foods, party items and window treatments.

Starting in January, Penney will downsize the Joe Fresh shops in its stores, reduce the assortment and move the clothing brand owned by Loblaw Cos Ltd <l.to> away from the front door to give a more prominent spot to its own a.n.a and jcp women's wear. It is eliminating jcp menswear.

The company is also reducing the assortment in top designer Michael Graves' home goods collection, whose sales Ullman said were good for some items but did not warrant all the store space it was getting.

Penney still sees potential in some of the brands Johnson brought in. It is testing ways to make the Jonathan Adler and Terance Conran home goods lines more successful, said Chief Merchant Liz Sweney. That includes selling Adler bedding with like brands, for example, since Penney shoppers prefer to browse by product category.

Still, the company is moving fast to shed merchandise that is not carrying its weight, given the urgency of getting sales back up to previous levels.

"We don't have six or seven years to get our business back," Ullman said. "Half of our business has to be brands that we can produce profitably."

(Reporting by Phil Wahba in New York; Editing by Jilian Mincer and Lisa Von Ahn)

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.