Jerry Robinson Dies at 89: Joker Creator, Comics Legend [INTERVIEW]

On Dec. 8, 2011, comics legend Jerry Robinson, the creator of such iconic Batman characters as Robin and the Joker and a pioneer for writers' and artists' rights in the comics industry, died in his sleep at age 89.

Robinson served as president of both the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC) and the National Cartoonists Society (NCS) during his lifetime, and received some of the highest honors in the comic world, including the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award and his induction into the Comic Book Hall of Fame.

For years Jerry Robinson (and to a lesser extent Bill Finger) battled with Batman creator Bob Kane over the rights to and credits owed for the characters all three had created. Even when Robinson was inducted into the Comic Book Hall of Fame in 2004, he and Kane were still arguing about the genesis of the Joker, with Robinson arguing that his status as hired hand at DC meant many of his ideas were co-opted later on.

It is a common story in the history of comics, and one of the reasons Jerry Robinson became a comics rights advocate. Throughout the 1970s, Robinson fought to get Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the creators of DC's Superman, to win full recognition and compensation for their work.

It also inspired him to form the Cartoonists & Writers Syndicate, now CartoonArts International, back in 1977. His goal was to bring American readers comic art and political cartooning from around the globe, and to help represent and distribute the work of rising artists the world over. As of 2010, CAI works with more than 550 artists from over 75 countries.

Many extensive obituaries will likely be published about Jerry Robinson in the days to come, detailing his early life, his battles within and without the comic world, and his extraordinary work as an artist, historian, activist, curator and author.

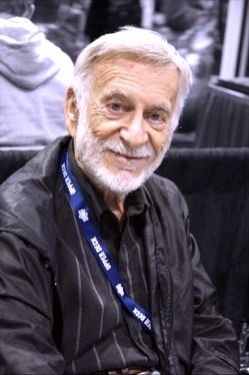

For my part, I would like to offer a glimpse into the Jerry Robinson of 2008, when I first met him: an 86-year-old firecracker, fresh off consulting with Heath Ledger on the Dark Knight set, ready to continue changing the fabric of comic art as we know it.

The following, an interview I held with him while still a college reporter at Columbia University's weekly magazine, covers his creation of the Joker, his work as a creative consultant on the Nolan's Batman films, and his tenure during the Golden Age of Comics.

Jerry Robinson was a living legend. But for me, he will always be a fellow Columbia graduate, a kindred spirit in the struggle to decide between journalism and art. He will always be the man who cemented my love of the comic universe, and of the characters he helped create.

Jerry Robinson, 2008

On Sept. 23, 2008, I sat down with Jerry Robinson, one of the great legends of the comics world and the mind behind some of the greatest characters in the Batman universe, including the Caped Crusader's sidekick Robin and the hero's dark mirror, The Joker.

Melanie Jones? he asked me during our first phone conversation.Your name's Melanie Jones? His voice crackled at the edges, a combination of wry humor and over seventy years of shooting off ideas to whoever had the brains to listen.

Melanie Jones... I like it. Sounds like a comic name. He paused, chuckled. Melanie Jones: Girl Detective.

It was a good thing I was sitting down.

Melanie Jones: Let's talk about the Joker. How did you get the idea to have this very dark character, a mass murderer, tied to something as childlike and playful as a jester?

Jerry Robinson: I felt what we needed was a villain that was worthy of Batman. I wanted to create a villain worthy of testing him. There was always this dichotomy, where [many believed] if the villain was too strong he would overpower the hero. I was not of that school. The stronger the villain, the more the hero has to win at the end. Besides, I was always intrigued by villains ... and I wanted to have a character that had a contradiction in terms. A villain with a sense of humor would be different.

MJ: And the name “the Joker”?

JR: My family was all expert card players. My brother was a master bridge player, and while I wasn't in that league, I usually had a deck of cards around. I immediately related my villain to the jester playing card, and that night I drew out a first conception sketch of the Joker. My idea was that the card would be his “calling card.”

MJ: The Joker has been completely psychotic, a harmless prankster, and everything in between. How do you feel about different interpretations of your character throughout the years?

JR: Comics are a living art form. It changes with new authors and with the new audience. That’s what makes it vital and gives it longevity. It has to be reinvented [because] so much material is eaten up. You have to give it a fresh look now and then. There are very few characters that remain the same over time, or have that longevity altogether.

MJ: But didn’t some of the changes to the Joker come from the Comics Code Authority (a censorship board that regulates comics’ content and emerged during the early 1950s)? Did your ideas often get rejected in favor of “milder” fare?

JR: A lot of magazines did have to tread a fine line during the ’50s. ... We brought in many ideas that were rejected, but they were very happy to let us pitch them. The censorship was later, after I left comics, and it was mostly about the vivid crime stories. Some of them did get rather gruesome, and maybe they weren’t so appropriate for younger readers. But literature has been abounding with such characters, like Tales from the Crypt by Edgar Allan Poe and Little Red Riding Hood. To make it seem that juvenile delinquency was born at that time, to pin it on the comics is a bit unfair.

MJ: Originally, you went to Columbia intending to pursue a career in journalism. How did you get involved in Batman? Did you want a creative outlet, or were you hoping to use your artistic skills to earn some extra cash?

JR: It was a little bit of both, actually. I started working on Batman in 1939, a couple of months after the feature started. I saw it as a way to fund my way through college. I never thought it would become a career. It ended up being the perfect referral for me because I had ambitions in both directions, art and writing, and after a few years I became immersed in the whole genre of comics and narrative storytelling.

MJ: The 1930s have been called the “Golden Age of Comics,” and you worked alongside artists like Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster (Superman) and Jack Kirby (The Hulk, X-Men). Did you have any idea, when you were working, that comic books would come to have the impact and the legacy that they did?

JR: We knew it was a new form of storytelling, so it was exciting. We were pioneering, and everything was being done for the first time. There was no past, we couldn’t see the future, so there was only the present. And there was a certain realization, but we didn’t think of it in grandiose terms. It was an exciting time and a new medium, and we were very young. I was only 17 years old, and most of us were in our mid-20s. The editors were somewhat older. They came from the pulp magazines, which were the immediate predecessors of comics. They were mostly in literary publication, but the stories were inspired by the early pulps.

MJ: DC Comics recruited you as a creative consultant for The Dark Knight. Did Heath Ledger’s Joker go back more to your original interpretation?

JR: I went to the recent Hollywood premiere of The Dark Knight, and I attended the shooting when I went over to London. The new film was based on the original concept of the character. They gave it a new interpretation with Heath Ledger, but the character itself was darker, more sinister, and had the same motivations. So I was pleased that they used that as inspiration.

MJ: What do you think of the recent “rebirth” of comic characters in film over the past 10 years?

JR: It’s exciting to see Hollywood finally turning to superheroes because those heroes were wellgrounded, the stories were exciting, the characters were good, and the success of them attests to their enduring values that were largely ignored. Comics were once looked down on as literature, and people turned to the classics for film. This [rebirth] is an affirmation of what we were doing.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.