Jimmy Carter, A Transformative Diplomat Despite Iran

Jimmy Carter's critics turned his name into a synonym for weakness over the Iranian hostage crisis. But by any measure, he also scored major achievements on the world stage through his mix of moralism and painstaking personal diplomacy.

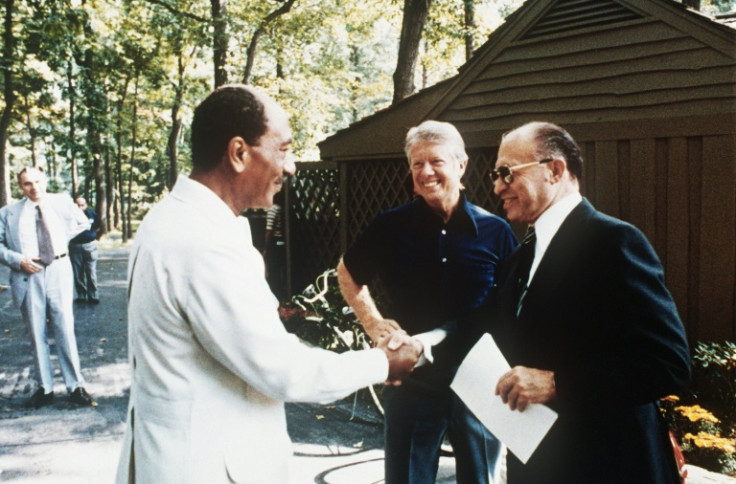

The 39th president of the United States, who died at age 100 on Sunday, transformed the Middle East by brokering the Camp David Accords, which established an enduring and once inconceivable peace between Israel and its most serious adversary at the time, Egypt.

Carter again brought a sense of righteousness and nearly obsessive attention to detail to negotiate the return of the Panama Canal to Panama, defying furor by US conservatives.

In two decisions with lengthy reverberations, Carter followed up on Richard Nixon's opening by recognizing communist China, and he began arming jihadists in Afghanistan who fought back against the Soviet Union, which would collapse a decade later.

But Carter was crushed by Ronald Reagan in the 1980 election in no small part due to foreign affairs after religious hard-liners toppled Iran's shah and seized US embassy staff, whose 444 days in captivity were broadcast nightly on US television.

Carter ordered an aborted rescue mission in which eight US troops died in a helicopter crash.

Asked at a 2015 news conference about his biggest regret, Carter replied: "I wish I'd sent one more helicopter to get the hostages -- and we would have rescued them and I would have been reelected."

The Iran debacle led to attacks that Carter was "weak," an image he would struggle to shake off as Republicans cast him as the archetypal contrast to their muscular brand of foreign policy.

The former peanut farmer's public persona did little to help, from a widely panned speech pleading for shared sacrifice to an incident that went the pre-internet version of viral in which Carter shooed away a confrontational rabbit from his fishing boat.

Robert Strong, a professor at Washington and Lee University who wrote a book on Carter's foreign policy, said the late president had been inept in public relations by allowing the "weak" label to stick.

"The people who worked with Carter said exactly the opposite -- he was stubborn, fiercely independent and anything but weak," Strong said.

"That doesn't mean he was always right, but he wasn't someone who held his finger in the wind allowing whatever the current opinion was to win."

Strong said that Carter defied his political advisors and even his wife Rosalynn by pushing quickly on the Panama Canal, convinced of the injustice of the 1903 treaty that gave the meddlesome United States the zone in perpetuity.

"Every president says, 'I don't care about public opinion, I'll really do what's right,'" Strong said.

"Most of the time when they say that, it's not true. To a surprising extent with Carter, it was true."

Carter, a devout Christian, vowed to elevate human rights after the cold realpolitik of Nixon and Henry Kissinger.

Years after the fact, he could name political prisoners freed following his intervention in their cases, and took pride in coaxing the Soviet Union to let thousands of Jewish citizens emigrate.

But the rights focus came to a head on Iran when Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi -- a Western ally whose autocratic rule by decree brought economic and social modernization -- faced growing discontent.

Reflecting debate throughout the administration, Zbigniew Brzezinski, Carter's more hawkish national security advisor, believed the shah should crush the protests -- a time-tested model in the Middle East.

Secretary of state Cyrus Vance, who would later quit in opposition to the ill-fated helicopter raid, wanted reforms by the shah.

Stuart Eizenstat, a top adviser to Carter, acknowledged mistakes on Iran, which the president had called an "island of stability" on a New Year's Eve visit a little more than a year before the revolution that ultimately saw the shah flee the country.

But Eizenstat said Carter could not have known how much the shah had lost support or that he was to die from cancer within months.

"It was the single worst intelligence failure in American history," Eizenstat said in 2018 as he presented a book assessing Carter as a success.

Uniquely among modern US presidents, much of Carter's legacy came after he left the White House. He won the Nobel Peace Prize more than two decades after his defeat at the polls.

The Carter Center, which he established in his home state of Georgia, has championed democracy and global health, observing elections in dozens of countries and virtually eradicating guinea worm, a painful infectious parasite.

Carter also took risks that few others of his stature would. He paid a landmark visit to North Korea in 1994, helping avert conflict, and infuriated Israel by asking if its treatment of the Palestinians constituted "apartheid."

But the accusations of weakness never went away.

Conservative academic William Russell Mead, in a 2010 essay in Foreign Policy magazine, called on then-president Barack Obama to avoid "Carter Syndrome," which he described as "weakness and indecision" and "incoherence and reversals."

Carter personally responded in a letter that listed accomplishments on the Camp David accords, China, the Soviet Union and human rights, while describing the fall of Iran's shah as "obviously unpredictable."

"Although it is true that we did not become involved in military combat during my presidency, I do not consider this a sign of weakness or reason for apology," he wrote.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.