Keurig Coffee Deal Leaves Bitter Taste With Short Sellers

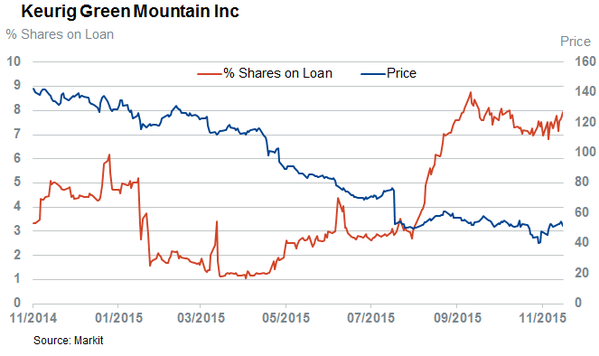

Keurig may have scalded some big short sellers Monday morning. At daybreak, about one in eight available shares of Keurig Green Mountain Inc. (NYSE:GMCR) was tied up in a short position -- a bet that the stock would fall. At $52, Keurig shares were already trading at a fraction of their November 2014 peak, but by an unusually large margin, and investors were predicting a further slide.

At 8 a.m., those short sellers got a rude awakening. JAB Holdings, a private group, reached a deal to take the K-Cup maker private for $93 a share, a 78 percent premium over Keurig’s going price. Short sellers caught wrong-footed saw an overall one-day loss of roughly $500 million, underscoring the difficulty even hedge fund luminaries have in divining market moves.

Keurig skeptics included David Einhorn, manager of the hedge fund Greenlight Capital. Einhorn announced in October that he had gone short on Keurig for a second time, after a notorious initial bet had fizzled between 2011 and 2014.

“The second time has been a charm,” Einhorn wrote in a letter to investors in October, calling the Keurig play “our third-biggest winner this year.” He entered the short at $102, meaning he could have made a 50 percent profit if he closed out before Monday.

But if Einhorn lacked that prescience, Greenlight could have seen one of its best bets sour in a matter of minutes. For a hedge fund that was down 17 percent year to date in the third quarter -- one of many underperforming funds -- that’s a bitter pill.

“This underscores the risk that you can be exposed to as an investor,” Simon Colvin, an analyst at Markit Analytics, said. “It’s painful, but it’s part of the nature of the game.”

Einhorn, who predicted the demise of Lehman Brothers in 2008, established Keurig as a favorite short in 2011, when he delivered a 110-page slide presentation highlighting the company’s expiring patents and raising questions over its financials. By November 2014, however, he was forced to exit his original short, calling it “ultimately unsuccessful.”

In a short position, an investor sells borrowed shares today hoping the price of those shares will fall. Later, the investor buys the shares on the open market and hands them back to the broker. The investor's profit is the difference between the original price and the current price.

If a stock goes to zero in the intervening time, the short seller can double his or her money. But potential losses are limitless, as the short seller has to eventually make good on the borrowed stock, the price of which can rise as high as the market will take it.

That potential downside can turn seemingly minor trades into colossal liabilities. Small-time investor Joe Campbell learned that the hard way last month when his short position on the tiny pharmaceutical company KaloBio blew up in his face, leaving him more than $100,000 in debt to online brokerage ETrade. KaloBio’s stock had exploded eightfold in a single day after the notorious pharma investor Martin Shkreli announced a stake in the foundering company.

College student and beginning investor Brandon Dempster nearly met a similar fate Monday. After taking a short position on Keurig in late November, Dempster covered his bet at a small loss last Thursday.

“Thank God I did or I would have ended up like that ETrade guy,” Dempster said Monday. “I’m relieved first and foremost.”

But bad shorts haven’t been the norm this year. “We’ve seen plenty of short sellers do really well in the market,” said Colvin, the analyst. Bets that energy companies and high-profile IPO stocks would tank have paid off. And as volatile market conditions in the second half of the year have dragged on equity investors, Colvin said, “Short sellers have been able to find underperforming shares.”

But even the best short-sellers can’t predict a surprise acquisition. “That is beyond the scope of what you can do,” Colvin said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.