Largest Deep Earthquake Ever Recorded Remains ‘Something Of A Mystery’ For Seismologists [PHOTOS]

Seismologists have been struck with a conundrum over the largest deep earthquake every recorded.

A 8.3 magnitude earthquake that struck the Sea of Okhotsk last May has scientists wondering how the massive earthquake could take place nearly 400 miles below the water’s surface.

"It's the biggest event we've ever seen," study co-author Thorne Lay, a seismologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz told LiveScience. "It looks so similar to shallow events, even though it's got 600 kilometers of rock on top of it. It's hard to understand how such an earthquake occurs at all under such huge pressure."

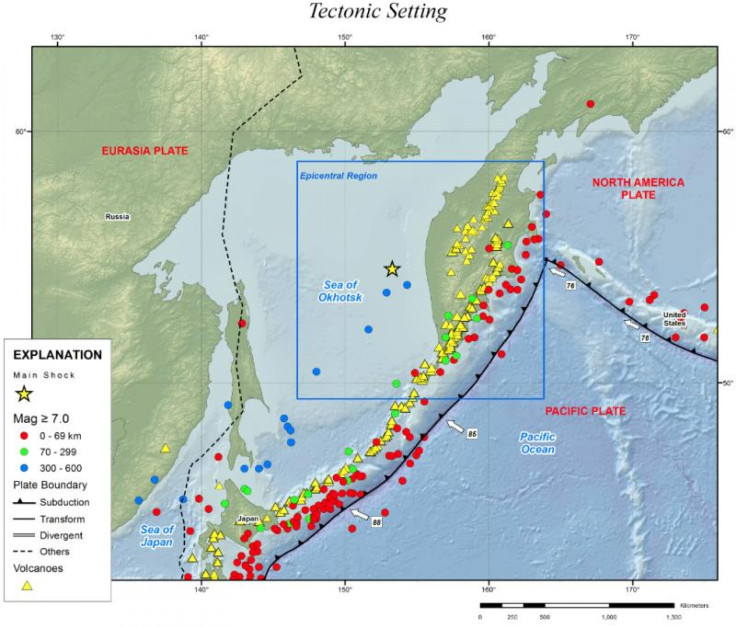

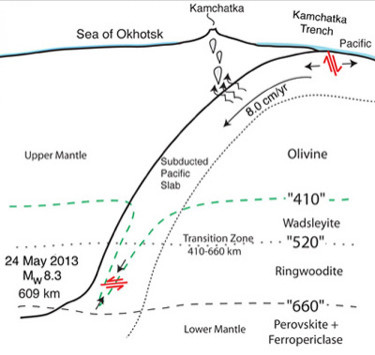

The earthquake on May 24 took place at a depth of 378 miles off the Russian coast right where the Pacific Plate presses into the Earth’s mantle – the layer between the crust and the outer core.

In a recent study published in the journal Science, a seismic analysis shows it was the largest deep earthquake recorded on Earth with a seismic moment 30 percent larger than the previously recorded 1994 earthquake in Bolivia that took place 395 miles underwater. While people in Russia felt the quake, there were no reported injuries or property damages in an area that’s home to a nuclear submarine base and where Russia's largest liquefied natural gas project is located.

"It ruptured just like a breaking of the glass," Lay said, explaining that the rupture took place at roughly 9,000 miles per hour. "And yet it's under this huge pressure, so that's something of a mystery. How does it happen?"

The precise mechanism that caused the rupture remains a mystery. One possible explanation could be that carbon dioxide or some other fluid seeped into the crack, lubricating it enough to allow the two slabs of rock to slide past each other at lightning fast speeds. But Lay adds that this would be unusual since all fluids should have been squeezed out of the slab at that depth.

"If the fault slips just a little, the friction could melt the rock and that could provide the fluid, so you would get a runaway thermal effect. But you still have to get it to start sliding," Lay said. "Some transformation of mineral forms might give the initial kick, but we can't directly detect that. We can only say that it looks a lot like a shallow event."

Compared to the Bolivia earthquake, this one was louder – sending more energy as seismic waves. The rock ruptured at a speed four times greater than what took place in Bolivia, yet the amount of stress released was much smaller making it resemble shallow earthquakes.

"It looks very similar to a shallow event, whereas the Bolivia earthquake ruptured very slowly and appears to have involved a different type of faulting, with deformation rather than rapid breaking and slippage of the rock," Lay said.

As for Russian residents that felt the earthquake and feared an impending tsunami, it was an unforgettable event. "The entire continent was shaken," Anatoly Tsygankov, head of Roshydromet's emergencies center, told the Interfax news agency.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.