Latin America's Virus Victims, And The Spaces They Leave Behind

An untouched exercise bike, a guitar that has gone silent, an empty couch -- these are just a few of the cherished possessions and everyday habits that tell the story of those who have died from Covid-19.

The global pandemic has claimed nearly one million lives, about a third of those in Latin America, where countries with overstretched medical resources are bracing for a new wave.

Across the region, AFP's photographers met the families of several victims, who have been forced to contemplate the empty spaces their loved ones have left behind.

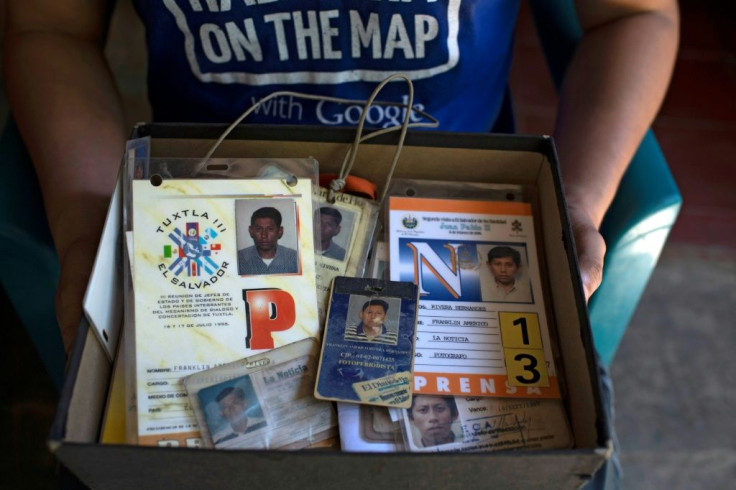

Victoria del Carmen says she still makes coffee every morning for her son Franklin Rivera, a Salvadoran photojournalist who was struck down by the virus at 52.

When he was well, Rivera liked to use an exercise bike in his modest Ciudad Delgado house on the outskirts of the capital, San Salvador. Now, it sits unused.

"No one can believe he is no longer with us," says his sister Geraldina Juarez. "We can't describe this emptiness."

To try to fill the void, his family are drawn to a box full of his old press credentials, eager to see his face once again.

Rivera's slow decline from the coronavirus began with a throat ailment on June 22 and then a urinary tract infection.

When he was finally diagnosed with Covid-19, he self-isolated at home.

Juarez remembers how tired he became, saying: "He could no longer walk much. He spent his days on his deck chair, which he set up in the yard."

He died after a lightning storm hit the city, unable to get a doctor with the emergency services at full stretch.

In the yard, the blue deck chair is still there, in the shade of a tree -- empty.

Paulo Roberto's blue guitar still hangs on the wall in his house in the southeastern Brazilian city of Belo Horizonte.

The small sofa where the 75-year-old liked to sit still bears his imprint.

"He used to spend a lot of his time on this sofa in the living room to watch films, documentaries and take a nap," said his wife Maria Candida Silveira.

The pandemic has taken a tough toll on the family of Roberto, who died in June.

Two of his four daughters contracted the virus, but only one lived to tell the tale. His 68-year-old wife fell gravely ill, but survived after a period in intensive care.

Now Silveira finds it difficult to put his absence into words.

"Sometimes you remember little details, moments we spent together, happy moments," she said.

"The memory of his music also remains, especially the old songs he loved to play and sing."

There is some consolation in knowing he was able to fulfill his dying wish: seeing his great-granddaughter Dudinha one more time.

"I made a video call from my phone. He was sitting on the bed, laughing and playing with her over the phone. He managed to say goodbye to her," she recalled.

Hugo Lopez Camacho's room stands as a monument to a humble life.

A blanket decorated with a football motif covers his single bed. His pillowcase is embroidered with the phrase "I think of you." A crucifix hangs on a brick wall.

Lopez Camacho lived on the property of a primary school in a Mexico City neighborhood, where his father is the caretaker.

He died in the same hospital where he had worked as an orderly for 14 years, wheeling patients to and from the surgical unit. He was 44.

At first, it seemed like he had a bad cold or the flu. Lopez Camacho had headaches. Then he started having trouble breathing.

He lost consciousness when he was hospitalized in late April. His mother never saw him again. He called when doctors said they would have to intubate him.

"He knew what was going to happen," his sister recalls.

Mexico's huge virus toll meant a backlog for funeral services, and the family had to wait for his remains to be handled.

They finally had to have him cremated, which was not their initial wish.

And now they have to wait again, to be allowed to bury his ashes in the family crypt, along with those of his grandmother.

Oscar Farias was a joker, and an expert in the art of the "asado," or grilling meat -- an institution in Argentina.

The 81-year-old former metal worker died alone in hospital in April, his family kept away by strict virus prevention protocols.

"It was the most devastating and overwhelming thing," says his daughter Monica, 45.

She wasn't even able to bring him a blanket when he called to say he was cold. They said their goodbyes on the phone.

"When I told him we would go and eat a pizza and have some wine when he got better, we were really saying goodbye," Monica says.

She had to sign the authorization for his cremation without even seeing his coffin.

She will keep in her mind an image of her father seen in a family photo -- a happy man, grilling some meat, and listening to tango on the radio.

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.