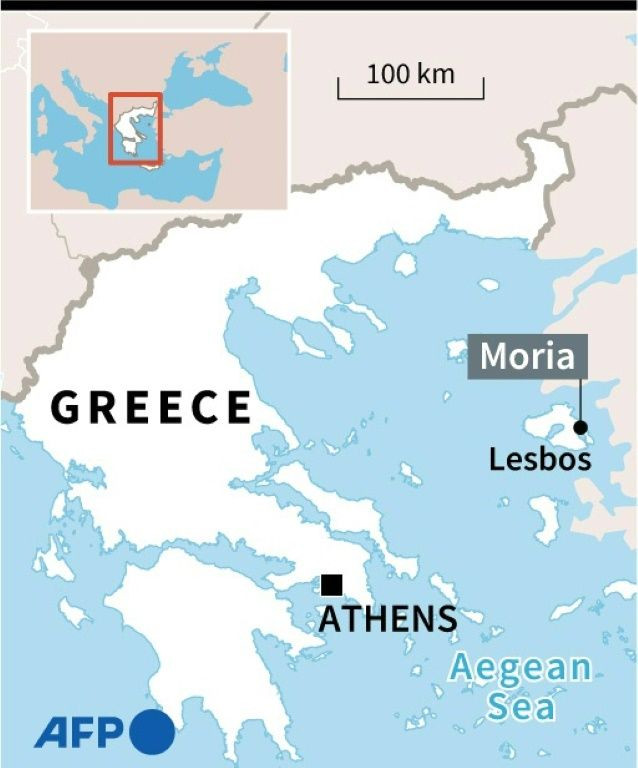

Greek Government Accuses Migrants Of 'Burning' Moria Camp

Greece on Monday accused migrants of deliberately burning their overcrowded camp last week on Lesbos island, where hundreds reluctantly moved to a new temporary site with "no showers or mattresses".

Families, children, young men and pregnant women have been left wandering aimlessly since a blaze ripped through the Moria camp on the night of September 8.

The fire has forced its 12,000 former occupants to sleep rough in abandoned buildings, on roadsides and even rooftops.

"The camp was burned by refugees and migrants who wanted to blackmail the government in order to be rapidly transferred from the island (to the continent)," Greek government spokesman Stelios Petsas told reporters in Athens.

He gave no further details. Greece's migrations minister last week made similar accusations, even before the conclusion of the investigation into what happened.

Officials have been hastily erecting a new camp of white tents near the eastern port-village of Panagiouda as exhaustion, hunger and fear set in among the migrants, and locals look on with trepidation.

Many of the former residents of Moria camp have refused to go there, fearing they will just be forgotten inside.

Others are reluctantly making their way to the site in the searing heat.

The new camp "seems harsh, with its direct sunlight and no shade. But I'm entering tomorrow as I have no choice," said Pariba, an Afghan woman.

Inside the site, which is closed to the press, Malik, an Algerian migrant, told AFP by phone that he had settled there with his wife and five children.

"There's nothing in the camp, no shower, no mattresses. There is only one meal per day, and they give us a carton with six bottles of water," said the French teacher.

He was living alongside some 200 refugees from Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq and African countries, he added.

Island residents meanwhile looked on with a wary eye, calling on European countries to lend a helping hand.

"We're afraid," said Savvas Afentoulis, 70, sitting at a cafe in Panagiouda. "Ninety percent of the people here are against the new camp, and all of us, we want them to leave the island.

"Greece can't handle the situation alone, the EU has to find a solution."

Afentoulis was quick to point out this was not always the case in Lesbos, the main port of entry for arrivals in EU member state Greece because of its close proximity to Turkey.

At the height of the migrant crisis that started in 2015, Lesbos saw hundreds of thousands of people arrive, many of them Syrians fleeing war, and residents united in solidarity to help them.

"But after, when Moria got full with people, they started to steal our sheep, and made damage," Afentoulis said.

Kostas Mountzouris, governor of the North Aegean region covering Lesbos, called on entrepreneurs and professionals to protest Tuesday and ask for "the removal of migrants from the island on board boats".

Not far from Panagiouda, four young Somalis who dream of going to France or Germany hoped to be allowed into the new camp. They too were scared.

"If we go there we are killed," said Ahmed, 18, showing the road where thousands of refugees are sleeping rough and then pointing to the nearby village.

Several European countries have signed up to a scheme to host unaccompanied minors from the destroyed Moria camp.

But that's around 400 people, a drop in the ocean.

Germany said Monday it was mulling taking in more migrants, possibly families with children.

In the meantime, Petsas said the government aimed to house everyone in the temporary camp within three to four days.

He also promised a permanent migrant processing centre in Lesbos soon, which would involve the European Union "so that (asylum-seeking) procedures progress more quickly".

European Council President Charles Michel, meanwhile, was due to discuss the situation on Lesbos when he meets Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis on Tuesday in Athens.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.