Life After Sumo: Retired Wrestlers Fight For New Careers

When Japanese sumo wrestler Takuya Saito retired from the sport at 32 and began jobhunting, he had no professional experience and didn't even know how to use a computer.

Athletes in many sports can struggle to reinvent themselves after retirement, but the challenge is particularly acute for those in the ancient world of sumo.

Wrestlers are often recruited early, sometimes as young as 15, and their formal education ends when they move into the communal stables where they live and train.

That can leave them in for a rude awakening when their topknots are shorn in the ritual that marks their retirement.

When Saito left sumo, he considered becoming a baker, inspired by one of his favourite cartoons.

"But when I tried it out, they told me I was too big" for the kitchen space, said the 40-year-old, who weighed in at 165 kilogrammes (26 stone) during his career.

"I had several job interviews, but I didn't have any experience... They rejected me everywhere," he told AFP.

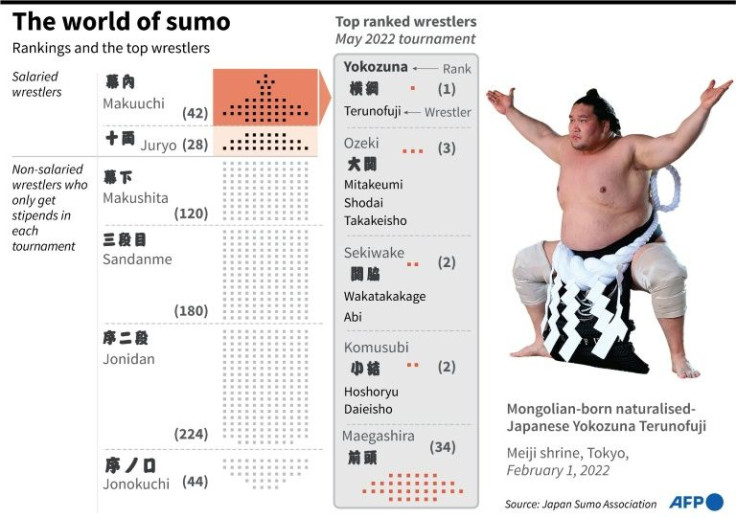

Professional sumo wrestlers or "rikishi" who rise to the top of the sport can open their own stables, but that's not an option for most.

Last year, of 89 professional wrestlers who retired, just seven remained in the sumo world.

For the others, the restaurant industry sometimes appeals, offering a chance to use the experience gained cooking large meals for their stablemates.

Others become masseurs after years of dealing with aching muscles, or leverage their heft to become security guards.

But trying to start over when non-sumo peers can be a decade or more into a career track is often demoralising.

Saito said he developed an "inferiority complex" and found the experience of jobhunting far harsher than the tough discipline of his life as a rikishi.

"In sumo, the stable master was always there to protect us," he said, adding that his former stable master offered him a place to stay, meals and clothes until his found his feet.

Many wrestlers leave the sport with little or no savings, because salaries are only paid to the 10 percent of rikishi in the sport's two top divisions. Lower-ranking wrestlers get nothing but room, board and tournament expenses.

Saito wanted to be his own boss and decided to become an administrative scrivener, a legal professional who can prepare official document and provide legal advice.

The qualifying exam is notoriously tough, and when Saito passed he opted to specialise in procedures related to restaurants, hoping to help other former wrestlers.

His first client was Tomohiko Yamaguchi, a friend in the restaurant industry with an amateur sumo background.

"The sumo world is very unique and I think that outsiders can't understand it," Yamaguchi told AFP, suggesting society can sometimes prejudge rikishi.

Wrestlers who go from being stopped for photos and showered with gifts can also struggle with fading into obscurity.

A rare few may end up with television gigs that keep them in the public eye, but for most, the limelight moves on.

Keisuke Kamikawa joined the sumo world at 15, "before even graduating high school, without any experience of adult life in the outside world," he told AFP.

Today, the 44-year-old heads SumoPro, a talent agency for former wrestlers that helps with casting and other appearances, but also runs two day centres for the elderly, staffed in part by retired rikishi.

"It's a completely different world from sumo, but rikishi are used to being considerate and caring" because lower-ranked wrestlers serve those in the upper echelons, explained Kamikawa.

Shuji Nakaita, a former wrestler now working at one of Kamikawa's care centres, spent years helping famed sumo champion Terunofuji.

"I prepared his meals, I scrubbed his back in the bath... there are similarities with care of the elderly," he said after a game of cards with two visitors to the centre.

And while the sight of hulking former rikishi around diminutive elderly men and women might appear incongruous, the retired wrestlers are popular.

"They are very strong, very reassuring and gentle," smiled Mitsutoshi Ito, a 70-year-old who says he enjoys the chance to chat about sumo with former wrestlers.

"Sumo is a world where you have to be ready to put your life in danger to win a fight," said Hideo Ito, an acupuncturist who has worked with rikishi for over two decades.

"For these wrestlers who are giving it their all, thinking about the future can seem like a weakness in their armour."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.