A Major Earthquake Is Overdue To Strike California, Say Seismologists

California earthquakes are a geologic inevitability. The state straddles the North American and Pacific tectonic plates and is crisscrossed by the San Andreas and other active fault systems. The magnitude 7.9 earthquake that struck off Alaska’s Kodiak Island on Jan. 23, 2018 was just the latest reminder of major seismic activity along the Pacific Rim.

Tragic quakes that occurred in 2017 near the Iran-Iraq border and in central Mexico, with magnitudes of 7.3 and 7.1, respectively, are well within the range of earthquake sizes that have a high likelihood of occurring in highly populated parts of California during the next few decades.

The earthquake situation in California is actually more dire than people who aren’t seismologists like myself may realize. Although many Californians can recount experiencing an earthquake, most have never personally experienced a strong one. For major events, with magnitudes of 7 or greater, California is actually in an earthquake drought. Multiple segments of the expansive San Andreas Fault system are now sufficiently stressed to produce large and damaging events.

The good news is that earthquake readiness is part of the state’s culture, and earthquake science is advancing – including much improved simulations of large quake effects and development of an early warning system for the Pacific coast.

The Last Big One

California occupies a central place in the history of seismology. The April 18, 1906 San Francisco earthquake (magnitude 7.8) was pivotal to both earthquake hazard awareness and the development of earthquake science – including the fundamental insight that earthquakes arise from faults that abruptly rupture and slip. The San Andreas Fault slipped by as much as 20 feet (six meters) in this earthquake.

Although ground-shaking damage was severe in many places along the nearly 310-mile (500-kilometer) fault rupture, much of San Francisco was actually destroyed by the subsequent fire, due to the large number of ignition points and a breakdown in emergency services. That scenario continues to haunt earthquake response planners. Consider what might happen if a major earthquake were to strike Los Angeles during fire season.

Seismic Science

When a major earthquake occurs anywhere on the planet, modern global seismographic networks and rapid response protocols now enable scientists, emergency responders and the public to assess it quickly – typically, within tens of minutes or less – including location, magnitude, ground motion and estimated casualties and property losses. And by studying the buildup of stresses along mapped faults, past earthquake history, and other data and modeling, we can forecast likelihoods and magnitudes of earthquakes over long time periods in California and elsewhere.

However, the interplay of stresses and faults in the Earth is dauntingly chaotic. And even with continuing advances in basic research and ever-improving data, laboratory and theoretical studies, there are no known reliable and universal precursory phenomena to suggest that the time, location and size of individual large earthquakes can be predicted.

Major earthquakes thus typically occur with no immediate warning whatsoever, and mitigating risks requires sustained readiness and resource commitments. This can pose serious challenges, since cities and nations may thrive for many decades or longer without experiencing major earthquakes.

California’s Earthquake Drought

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake was the last quake greater than magnitude 7 to occur on the San Andreas Fault system. The inexorable motions of plate tectonics mean that every year, strands of the fault system accumulate stresses that correspond to a seismic slip of millimeters to centimeters. Eventually, these stresses will be released suddenly in earthquakes.

But the central-southern stretch of the San Andreas Fault has not slipped since 1857, and the southernmost segment may not have ruptured since 1680. The highly urbanized Hayward Fault in the East Bay region has not generated a major earthquake since 1868.

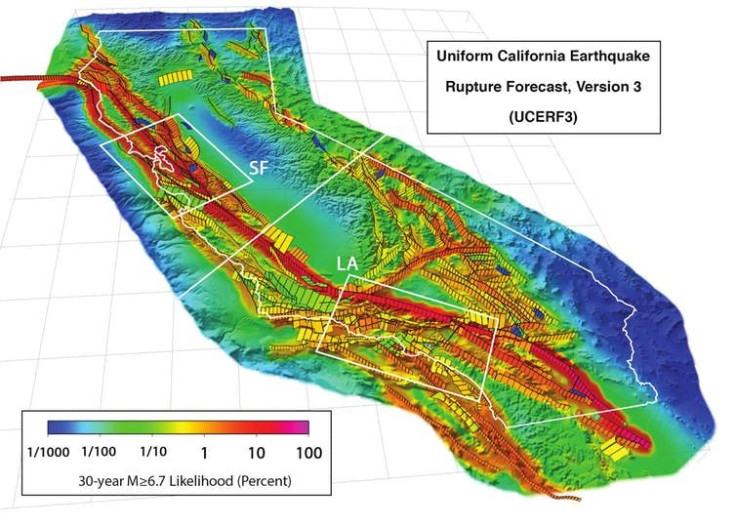

Reflecting this deficit, the Uniform California Earthquake Rupture Forecast estimates that there is a 93 percent probability of a 7.0 or larger earthquake occurring in the Golden State region by 2045, with the highest probabilities occurring along the San Andreas Fault system.

Can California Do More?

California’s population has grown more than 20-fold since the 1906 earthquake and currently is close to 40 million. Many residents and all state emergency managers are widely engaged in earthquake readiness and planning. These preparations are among the most advanced in the world.

For the general public, preparations include participating in drills like the Great California Shakeout, held annually since 2008, and preparing for earthquakes and other natural hazards with home and car disaster kits and a family disaster plan.

No California earthquake since the 1933 Long Beach event (6.4) has killed more than 100 people. Quakes in 1971 (San Fernando, 6.7); 1989 (Loma Prieta; 6.9); 1994 (Northridge; 6.7); and 2014 (South Napa; 6.0) each caused more than US$1 billion in property damage, but fatalities in each event were, remarkably, dozens or less. Strong and proactive implementation of seismically informed building codes and other preparations and emergency planning in California saved scores of lives in these medium-sized earthquakes. Any of them could have been disastrous in less-prepared nations.

Nonetheless, California’s infrastructure, response planning and general preparedness will doubtlessly be tested when the inevitable and long-delayed “big ones” occur along the San Andreas Fault system. Ultimate damage and casualty levels are hard to project, and hinge on the severity of associated hazards such as landslides and fires.

Several nations and regions now have or are developing earthquake early warning systems, which use early detected ground motion near a quake’s origin to alert more distant populations before strong seismic shaking arrives. This permits rapid responses that can reduce infrastructure damage. Such systems provide warning times of up to tens of seconds in the most favorable circumstances, but the notice will likely be shorter than this for many California earthquakes.

Early warning systems are operational now in Japan, Taiwan, Mexico and Romania. Systems in California and the Pacific Northwest are presently under development with early versions in operation. Earthquake early warning is by no means a panacea for saving lives and property, but it represents a significant step toward improving earthquake safety and awareness along the West Coast.

Managing earthquake risk requires a resilient system of social awareness, education and communications, coupled with effective short- and long-term responses and implemented within an optimally safe built environment. As California prepares for large earthquakes after a hiatus of more than a century, the clock is ticking.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the original article.

Richard Aster is a Professor of Geophysics, Colorado State University.