Marijuana Legalization 2015: PTSD And Cannabis -- Can Researchers Cut Through The Politics To Find Out Whether Weed Works?

CASCADE, Colorado -- Matt Stys funnels a mound of finely ground God’s Gift, a sativa strain of marijuana, into his multicolored glass bowl and takes a hit. “It allows the images and all the things in your head to lose focus and drift away for a while,” says Stys as wisps of smoke curl from his mouth. For Stys, the images of being a noncommissioned officer running an entry control point in Iraq in 2007 and 2008 can fade away with the smoke: recollections of struggling to differentiate potential combatants from Iraqi citizens, of watching the wounded and dead flowing through his security checkpoint. Other demons in his head can waft away too, like the memories of spending his teenage years in foster care, and the moral ache of questioning the war in which he fought.

“I had this misconception that we were over here to help Iraq,” he says. “But we were just there to destroy a nation.”

These images and anguish caused the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to diagnose Stys, 43, with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), along with service-related shoulder, knee and ankle injuries this past March, six years after getting out of the Army. Stys sees a VA therapist, but he’s not taking drugs for his condition -- that is, except for cannabis, for which he has a Colorado medical marijuana card. He says the marijuana helps him sleep, manage anxiety and avoid succumbing to road rage. And cannabis helps Stys avoid the other substance he’s used to keep the images away: alcohol, which led him to fall asleep behind the wheel in 2009. He somehow managed to avoid ending up dead or in jail.

“No one is saying this is a cure-all, but it is a cure,” says Stys, his dark, tired eyes gazing out the window of his mountainside cabin. “There has to be a nuanced understanding of what cannabis is, how it affects people, how it can help with pain management, PTSD and war wounds.”

After steadily accumulating anecdotes about how veterans use cannabis to treat their war wounds that understanding might finally be on the way. Following years of bureaucratic hurdles, the first Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved, randomized controlled trial on cannabis and PTSD is set to begin this summer. Many believe the study will spur increased acceptance of veterans using marijuana, a political shift that’s already led more and more states to add PTSD to their lists of conditions that qualify for medical marijuana.

But that key study still faces roadblocks, the latest being a VA hospital’s refusal to let one of the trial’s researchers recruit patients at its facility. It’s just one more example of the political and scientific obstacles that remain before cannabis is embraced as a viable option for soldiers. While the idea of veterans becoming medical marijuana patients has proven to be a powerful political leveraging tool, the concept gives some people pause. Amid reports of skyrocketing substance abuse among veterans, overworked VA doctors and increasingly potent marijuana offerings, some worry that exposing the nation’s wounded warriors to cannabis might in some instances do more harm than good -- and in extreme cases, lead to even more violence and tragedy.

More than for any other potential medical use for marijuana, the clock is ticking to nail down the science behind cannabis and PTSD. According to a 2014 report by the RAND Corporation’s Center for Military Health Policy Research, approximately 300,000 of the 1.64 million service members who deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan as of October 2007 were suffering from PTSD or major depression. Only about half of that number had sought treatment in the previous year, and of those who did, just over half received a "minimally adequate treatment." And with hundreds, if not thousands, of these struggling veterans killing themselves each year, advocates argue that if marijuana can help reduce the death toll there’s not a minute to lose.

From Vice To Remedy

“There is big sense of urgency,” says Sue Sisley, sitting in a café early on a Sunday morning in Denver, where she was presenting at a medical seminar. “We do have an epidemic of veteran suicide in this country. The question is, is the epidemic related to untreated or underdiagnosed PTSD, and could marijuana help deal with that epidemic?” Sisley aims to help answer the question with the study she launched, the first and only FDA-approved trial on PTSD and medical marijuana, which she has spent years fighting to get off the ground.

Sisley says she gets phone calls all the time now: "I have PTSD, but the meds I’m on make me feel awful. Could marijuana help? Can you help me figure out what to do?" Sisley, a lifelong Republican psychiatrist, has become the unwitting face of understanding cannabis’ scientific potential for struggling veterans. It’s why she travels constantly, speaking all over the country, as well as in Israel, Canada, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Austria and the Czech Republic in the past year. “I am in a unique position here,” she says. “I feel like I have an important story to tell about how science has been trumped by politics.”

That story began about 10 years ago, when veterans who saw Sisley at her private practice and indigent clinic she ran in Scottsdale, Arizona, began disclosing that they were using marijuana and it was helping. Sisley was skeptical, but she started documenting these incidents and found that unlike most pharmaceuticals that target a specific ailment, cannabis seemed to help with a variety of the conditions plaguing veterans, including anxiety, flashbacks and lack of sleep. “PTSD has such a broad constellation of symptoms,” she says. “And you can end up taking eight, 10 medicines to manage a single syndrome. This plant enabled them to walk away from all of these drugs.”

To Sisley, it was clear her veterans were using marijuana medicinally. But for a long time, marijuana use among soldiers was seen as an example of America’s finest falling prey to a dangerous vice. In the 1970s, pot and heroin use was so high among soldiers returning from Vietnam that President Nixon instituted mandatory drug testing to identify those who needed treatment. “I don’t even think it was seen as recreational among soldiers,” says Michael Krawitz, executive director of the advocacy group Veterans for Medical Cannabis Access. “It was just part of the culture of the time, the culture of Asia. We sent these military guys over to Asia where they had been using cannabis for a thousand years. It took a while before the veterans realized they were using it medicinally.” But eventually many former soldiers did come to embrace cannabis’ medicinal potential, and this helped spur the growth of the medical marijuana movement in the 1990s. Vietnam veteran Dennis Peron, for example, was co-author of California’s Compassionate Use Act of 1996, the first successful medical marijuana ballot initiative.

But while veterans helped jumpstart recognition of cannabis’ potential medical benefits, many of them have limited access to medical marijuana themselves. Because cannabis is still illegal under federal law, federal employees such as VA doctors can’t recommend the substance as treatment. “Marijuana was an unspoken word in the VA system,” says Krawitz. “I have been working on veterans issues for a long time, and I cannot remember another issue where the freedom of speech of VA doctors came into play. Agent Orange, Gulf War syndrome, throughout all of those issues, doctors at the VA were our partner. This was the one issue where doctors were not able to talk with their patients about it.”

In some cases, veterans say their VA physicians wouldn’t just avoid talking about medical marijuana, but actively penalized them for using it. Jack Stiegelman, founder of the Florida-based organization Vets For Cannabis, says a 2004 deployment in Afghanistan left him with a serious back injury for which he was prescribed daunting amounts of morphine and muscle relaxants. There was also the PTSD that led him to wake up screaming in the middle of the night, threatening his squad leader with physical violence. “I said I was going to put my foot through his teeth,” says Stiegelman. “I felt it was their fault for not taking care of me.”

Eventually, a friend suggested he try smoking marijuana before bed, instead of washing down his pain pills with a six pack of beer. The relief, says Stiegelman, was immediate. “The rage wasn’t there anymore,” he says. “It helped with the stabbing pains and relaxed my back spasms, and it helped me think clearly and stay in tune with my body.” But when his doctors learned he was using marijuana, Stiegelman says they cut him off from the pharmaceuticals he’d been prescribed, causing him to buy pain meds on the black market for years until he kicked the habit. “They told me I was violating my narcotics contract, so they had the right to remove me from all of my narcotics,” he says. “The VA would give me six medications in three bags, but because I took medical marijuana to stop some of the effects of the other medications, they said I was a drug addict.”

VA spokeswoman Ndidi Mojay notes that federal law prohibits VA physicians from prescribing medical marijuana and from completing forms and paperwork necessary for patients to enroll in state marijuana programs. However, “VA does not administratively prohibit VA services to those veterans who participate in state marijuana programs," she says. "In some cases, participation in state marijuana programs may be inconsistent with treatment goals and therefore VA clinicians may modify treatment plans for the health of the patient.”

A major stumbling block is that there’s still little scientific research related to marijuana’s medical benefits, particularly when it comes to one of the signature injuries of modern veterans: PTSD. Arguments for using cannabis to treat PTSD got a boost last year when New Mexico psychiatrist George Greer published in the Journal of Psychoactive Drugs the results of a chart review of 80 veterans he worked with who had PTSD and used marijuana. He found that on average, patients using cannabis reported a 75 percent reduction in several of the main symptoms of PTSD, including hyperarousal and re-experiencing traumatic episodes. “This is a watershed,” says Greer. “You think of people being stoned on marijuana, you don’t think of them being more functional. It has to be a historical thing for marijuana to be found at least in anecdotal reports to be helpful for people for psychiatric conditions.”

But like all existing research on cannabis and PTSD, Greer’s study was based on anecdotal evidence, not the gold standard of scientific research: a randomized clinical trial. “We are at the point where self-report data is overwhelming and generally positive regarding medical marijuana and PTSD,” says Mitch Earleywine, a professor at SUNY Albany and chair of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML)’s board of directors. “Unfortunately, there has never been a randomized clinical trial or anything like that.”

That’s exactly what Sisley aimed to do. In 2010, she submitted to the FDA a study design for what would be the first randomized control trial of marijuana and PTSD. Five months later, she had FDA approval.

“I was so excited,” she says now. She didn’t realize what lay ahead.

Research Roadblocks

Political momentum for linking PTSD and medical marijuana is growing. Of the 23 states that now allow for medical marijuana, nine include PTSD as a qualifying condition for the drug, and in three others doctors have broad discretion to recommend medical cannabis for PTSD or other ailments. In 2010, the VA published a directive stating veterans shouldn’t be punished for using medical marijuana in those states that allow it, but reiterated that its doctors can’t help veterans obtain the treatment. Now, even that restriction could be lifted. In May, a Senate committee passed a bipartisan amendment to a military spending bill that would allow VA doctors to recommend and fill out paperwork for medical marijuana in states where it’s legal; the final bill will be negotiated later this year.

But in many jurisdictions, PTSD and marijuana remains a political sticking point. In Colorado, which has some of the most liberal cannabis laws in the world, PTSD still doesn’t count as a qualifying condition for obtaining medical marijuana. And while PTSD is the No. 1 reason for which people obtain medical marijuana cards in New Mexico, there have been multiple initiatives to remove it from the state’s list of qualifying conditions.

Part of the problem is that PTSD is unique among medical marijuana conditions, since it is a psychiatric disorder, not a physical ailment. “One of the issues with PTSD with medical marijuana is it is the first mental condition to be considered,” says John Evans, founder of the organization Vets 4 Freedoms. He helped add PTSD to Michigan’s list of medical marijuana-approved conditions in 2014 and petitioned to add the condition to Colorado’s list earlier this year. The Colorado Board of Health will hold a hearing on the issue on July 15. “It bothers a lot of people in the psychiatric community and the prescription-drug world,” says Evans.

“It’s a catch-22,” says Dan Riffle, director of federal policies for the Marijuana Policy Project. “People want to have hard data on how medical marijuana works for PTSD. But you can’t say that and then actively block the research. And that’s what’s happening on a federal level.”

Sisley ran into those challenges after she obtained FDA approval for her PTSD study. Unlike research on other Schedule I drugs such as LSD and heroin, the government required an extra Public Health Service (PHS) review for marijuana studies not funded by the government and that all research-related cannabis be obtained from a marijuana grow at the University of Mississippi that’s administered by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). “NIDA and PHS had no timetable for an approval,” says Sisley. “In the three years it took PHS to approve my trial, roughly 24,000 veterans committed suicide. And here we are in Colorado, where I could have had marijuana grown to spec within three months.”

In June, one of those additional requirements was removed when the Obama administration eliminated the PHS review for marijuana studies. For Sisley, this is a step in the right direction -- but as she added in a statement, “The next and even more crucial reform is ending the monopoly on DEA-licensed marijuana that can be used in FDA-regulated research, a monopoly that is currently held by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Once there are privately-funded, DEA-licensed medical marijuana producers, then the question of the medical use of marijuana will be evaluated by the FDA based on scientific data, the same as with all other drugs.”

Over the past few years, Sisley has faced additional headaches on the local front. Although she was a part-time professor at the University of Arizona, Sisley was told by university administrators that she couldn’t run the study on campus. Even after a state bill passed allowing marijuana research on campuses and Sisley’s study received PHS approval in March 2014, the administration wouldn’t budge. (It likely didn’t help that the outspoken Sisley had formed her own political action committee to help her cause.) Then, in June 2014, the university told Sisley her employment contract wouldn’t be renewed. While the given reason was funding issues, Sisley believes she’d made too much noise about marijuana. “They were terrified of the optics of vets puffing away on campus,” she says.

But Sisley wasn’t down for the count – and soon enough, she had backing from several unexpected sources. Marcel Bonn-Miller, a University of Pennsylvania professor who also holds positions at the VA’s National Center for PTSD and its Center of Excellence in Substance Abuse Treatment and Education, reached out to the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies and asked if he could help with the research in his capacity as a UPenn professor. Then, in December 2014, the Colorado Board of Health awarded $2 million to the study as part of roughly $8 million in medical marijuana research grants funded by state medical marijuana registration fees. Now the plan is to run a placebo-controlled, randomized study on how different marijuana strains affect 76 veterans with PTSD split between two research sites -- one overseen by Sisley in Arizona, and one at Johns Hopkins University in Maryland -- with Bonn-Miller coordinating the efforts.

But even with major state funding and new collaborators, Sisley is still encountering obstacles. She’s struggled to find a landlord in the Phoenix area willing to lease her space for her half of the study, and she and her colleagues are still waiting on the University of Mississippi to grow a strain of marijuana that’s high enough in the much-touted chemical cannabidiol (CBD) for use in the trial. Furthermore, this spring the VA Medical Center in Phoenix informed her that she couldn’t speak at the facility about her research in hopes of getting doctors to refer patients for the trial, even though she’s spoken at the hospital about the study in the past.

“The Phoenix VA Medical Center cannot work with Dr. Sisley on her marijuana research study, or on any other research study,” says hospital spokesperson Jean Schaefer. “Dr. Sisley is neither credentialed to practice in VA nor approved by the local research oversight committees to conduct research at Phoenix VAMC.”

Still, Sisley remains committed to running the study in Arizona, even though it might be easier for her to do so in a state like Colorado. “My feeling is the study was conceived in Arizona, and that’s where it should stay,” she says. “We are not going to be run out of town by my opponents. I want to find a space in their own backyard, where they are forced to examine this.”

Bad Medicine?

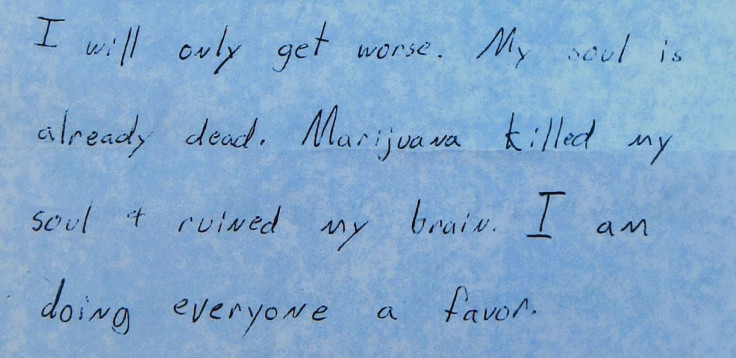

As a child of the ’60s who’d smoked marijuana herself, Sally Schindel never thought cannabis could be harmful. That was until her son, Andy Zorn, hanged himself in Peoria, Arizona, in March 2014 and wrote in his suicide note, “Marijuana killed my soul [and] ruined my brain.”

Zorn, who served as a paratrooper in Iraq in 2003 and 2004, had been deteriorating for years – struggling with depression, unable to hold down a job, lashing out in several incidents that landed him in mental health facilities. But Schindel didn’t suspect marijuana was part of the problem until she’d read his suicide note and began doing her own research on cannabis and addiction. She came to conclude he’d spent more than $80,000 on drugs, mostly marijuana, and she learned that doctors had diagnosed him with severe cannabis use disorder. Now Schindel, who lives in Prescott, Arizona, is convinced that marijuana put him over the edge.

“My objective now is to spread my son’s message that marijuana killed his soul and ruined his brain,” says Schindel, who currently volunteers full-time for Arizonans For Responsible Drug Policy, which opposes legalization of recreational marijuana. “My experience with PTSD and depression is that marijuana initially might seem helpful, but in the end, I strongly believe it’s very harmful.”

Schindel isn’t alone in her concerns. Those opposed to using marijuana to treat PTSD point to studies that suggest cannabis can increase psychotic disorders, anxiety, depression and suicidal tendencies. What’s more, a recent observational study of 2,000-plus veterans seeking VA treatment for PTSD found that those who never used marijuana exhibited significantly less severe symptoms four months later than those who started or continued to use marijuana. Those who began using cannabis after being admitted for treatment displayed the highest levels of violent behavior.

“The epidemiological data gives no evidence for a benefit in terms of psychiatric well-being, and every bit of evidence of harm,” says Christine Miller, a molecular neuroscientist who’s director of the Maryland chapter of Smart Approaches to Marijuana, an anti-legalization group. There’s also a concern that struggling veterans could be predisposed to becoming marijuana addicts; cannabis use disorder is the most diagnosed type of substance abuse among veterans in the VA with PTSD -- more than 40,000 veterans had been diagnosed with the disorder as of 2014. Could the promotion of marijuana as a PTSD treatment lead to more veterans developing a dangerous dependence on the drug?

“There is absolutely cause for concern among certain vulnerable segments of the PTSD population,” says Bonn-Miller of the VA’s National Center for PTSD. “This is not a black and white issue. As evidence has consistently documented, marijuana has been associated with a number of psychological symptoms and disorders, particularly among especially vulnerable sub-segments of the population.”

To Miller of Smart Approaches to Marijuana these associations undermine the need for clinical research on marijuana and PTSD. “In my view, it would be extremely difficult to conduct those studies in an ethical manner, given what is already known about the negative effects of THC on symptoms that already plague that patient population,” she says.

Bonn-Miller disagrees. “We are excluding particularly vulnerable populations who are at high risk of experiencing problems following marijuana use,” he says. “We are also monitoring adverse events throughout the study. These measures were instituted exactly so we don't harm folks with PTSD during the clinical trial.”

Schindel, for one, isn’t opposed to Sisley running her part of study in her home state of Arizona, despite what she believes the drug did to her son. But she doesn’t think local VA facilities should be involved. Are overworked VA doctors in the best position to parse the nuances of cannabis use and PTSD – or would some just use the option of recommending medical marijuana to shirk their own responsibilities?

Maybe all of these arguments, from both proponents and opponents of marijuana use for PTSD, make the study launched by Sisley and now overseen by Bonn-Miller all the more necessary. Maybe it’s research like this that will help determine what sort of optimized dosages and administration methods could best offer relief to ailing veterans like Matt Stys and Jack Stiegelman -- and what sort of rules and restrictions need to be in place to prevent more deaths like that of Andy Zorn.

The Magic Time

Even without the Phoenix VA hospital’s support, Sisley remains optimistic that thanks to media attention and veteran advocacy, she’ll find the trial subjects she needs for her half of the trial. At the same time, her counterpart at Johns Hopkins, psychiatry professor Ryan Vandrey, has his lab site ready to go and is waiting for final approval from his university’s internal review process. He could even be up and running in the next few weeks.

Meanwhile, media attention on Sisley’s struggle to get her study off the ground might have had an unintended consequence: Now, more than ever, people are talking about medical marijuana and PTSD. “Veterans are pointing out the obstruction of research on this at the federal level, and they’re using this study as an example,” says Rifle of the Marijuana Policy Project. “It has shone a light on the fact that there is no great treatment for PTSD.”

That message could get a boost on Veterans Day, Nov. 11, when veterans from around the country will congregate in Washington, D.C. for what they've dubbed #SmokeDownVeteransAffairs, protesting the military’s reluctance to embrace medical marijuana.

Sisley intends to be there – but in the meantime, she’s focusing her attention on finding a suitable location to run her trials in Arizona. She’s also getting ready to obtain the marijuana she needs from the University of Mississippi, even though the samples being grown haven’t yet reached the levels of CBD requested for trial. “I am hoping this summer will be the magic time,” says Sisley. “If my enrollment is really rapid, I might be able to get all of my data within a year.”

Yes, she knows there might be more hurdles to overcome before it’s all said and done, but at this point, Sisley says as she cracks a wry smile, she’s used to it. “We don’t take the path of least resistance.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.