Marijuana Legalization 2015: Should America Regulate Pot Just Like Alcohol?

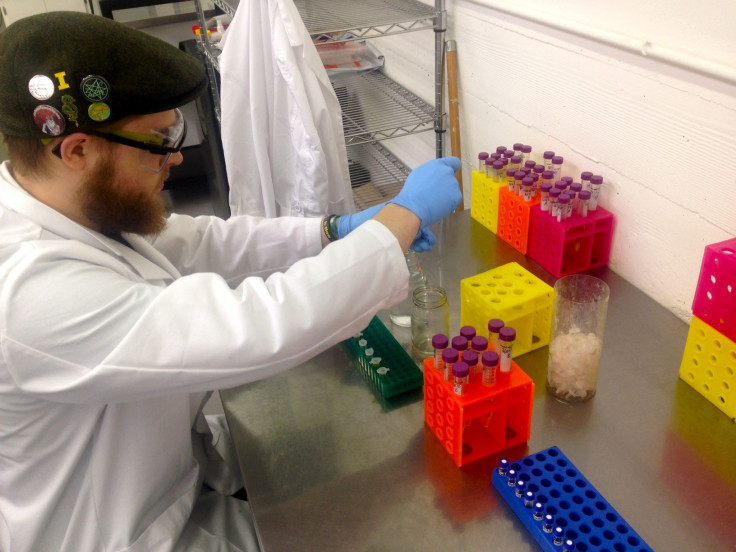

SEATTLE -- Steve McNalley was in his usual spot last Tuesday, hunched over a stainless steel workbench as he used a pipette to carefully filter particulates such as waxes and plant membranes from pulverized marijuana across a row of test tubes and vials at Analytical 360 labs in Seattle. His samples had already succumbed to microscopic imaging and at least 24 hours of dehydration.

Next, the concentrated marijuana will undergo high-performance liquid chromatography to determine its potency for compounds including THC, the ingredient that causes the sensation of being high.

“You’re not going to find alcohol or even cigarettes tested as much,” John Brown, co-founder, says from the stout warehouse that his lab occupies in the city's industrial district.

Twenty-three states now allow marijuana to be distributed within state borders for medical purposes, and four have also opted to permit recreational use. McNalley's careful measurements represent just one of the ways in which public health officials are attempting to reconcile their lack of expertise on marijuana with a voter-imposed mandate to regulate the budding businesses that sell it.

For a long time, medical marijuana was approved in a handful of states but went largely unregulated. Once the substance was approved for recreational use by voters in Colorado, Alaska, Washington and Oregon, public health officials knew they would have to follow up with sensible policies for a substance that remains largely illegal and poorly studied in the U.S.

But deciding who gets to sell this marijuana, whether and how the marijuana should be tested for contaminants and what exactly it means to protect the rights of consumers or patients to safely purchase a federally banned substance remains a work in progress.

“States are currently making the decision on how they want to treat it as a public health issue,” Hilary Bricken, lead attorney at the Canna Law Group in Seattle, says from her office in a slick high-rise in downtown Seattle. “Is it a party drug or is it Tylenol? And if it’s both, how do we harmonize that?”

Weed And Booze

Amid the uncertainty, some states have decided to treat marijuana just like another formerly illicit substance -- alcohol. Voters in Oregon and Washington placed weed under the authority of a state liquor control commission or board -- the same agency that issues liquor licenses to restaurants and bars, and conducts compliance inspections to make sure these facilities are not selling to minors. Congress is currently considering a bill that would permit all states to regulate and tax marijuana in this manner.

In some ways, such an arrangement makes a lot of sense -- liquor control agencies have decades of experience maintaining tightfisted control over a liquid drug that causes far more deaths per year than marijuana. Many of the public health goals for both marijuana and alcohol are the same -- limit the amount that drivers have in their systems, for example, and keep it out of reach of minors. And, of course, the revenue that states stand to collect from hefty taxes on these products is substantial.

But Tom Towslee, communications director at the Oregon Liquor Control Commission, admits that the idea of regulating marijuana as alcohol soon runs up against practical limits.

“We've been regulating liquor in Oregon since after Prohibition, so we're pretty good at it,” he says. “Marijuana is a new animal.”

State governments do not oversee the production, processing and packaging of alcohol -- but they must for marijuana. The state does not have to determine what constitutes a safe alcoholic product -- it merely distributes bottles once they are produced. And unlike alcohol, health officials know little about the risks of marijuana, which makes it hard to determine what potency is appropriate in a pot brownie versus a joint smoked by a cancer patient, for example.

“This is where the liquor control board falls short as the agency that should be dealing with this,” Bricken says.

There are technical and logistical hurdles, too. For example, Towslee’s office is next to the state’s liquor distribution warehouse. “There's 2 million bottles of booze sitting in there,” he says. Those bottles are closely tracked by the state. If a bar wants to order a bottle of Pappy Van Winkle bourbon, the owners place an order with the state, which ships it to the warehouse and then out to licensed restaurants and grocery stores.

But oversight of marijuana cannot work this way because state law forbids the agency from possessing marijuana. That means Oregon will have to develop a separate system -- a combination of software and barcode scanners, most likely -- to trace marijuana through the state without ever touching it.

“The biggest thing is a tracking system that tracks marijuana from seed to sale,” he says. “We track liquor, but liquor doesn't grow. Tracking a plant is a lot harder than tracking a bottle of liquor.”

There is one state to turn to for advice on this matter, at least -- Colorado tracks marijuana plants from greenhouse to retail shelf by using tags equipped with radio frequency identification technology that link into a digital database maintained by the Colorado Department of Revenue. That system has been called the “backbone of Colorado’s regulatory structure” by John Hudak of the Brookings Institution. Last month, the Oregon Liquor Control Commission requested $1.9 million to hire a contractor to build its own system by January 2016, the design of which is still to be determined.

Another difference between overseeing alcohol and marijuana sales in the state? Oregon’s liquor commission has also asked for $636,000 to upgrade the security at its entrance, since marijuana businesses often pay taxes in cash due to a lack of banks willing to work with them.

“We're anticipating taking in anywhere from $400,000 to $500,000 a month through the front door in cash -- quite aromatic cash, from what I understand,” Towslee says. The money from the budget request will go toward security features such as cameras and a vault. One day two weeks ago, a banker stopped by to show Towslee a safe deposit system that could help the agency keep large amounts of cash secure.

In addition to sorting out security and closely tracking marijuana plants, states must also set standards for potency and dosing as well as require dispensaries to test batches of weed for contaminants such as mold, microorganisms and pesticides. None of these responsibilities fall to state officials when it comes to alcohol, but they are necessary to ensure the safety and quality of the state's marijuana supply.

“If people are going to complain about where their yogurt comes from or whether there’s antibiotics in their chicken, they may care about what’s in their pot,” Bricken says.

Washington has certified 14 labs -- including Analytical 360 -- to run tests on samples of marijuana for mold, metals and potency, which the state now requires for every batch of weed sold at a recreational dispensary in the state. Starting next year, medical marijuana will also be subject to mandatory testing.

“The challenge was creating Washington's recreational rules and regulations when nothing existed like it anywhere else in the world,” Brian Smith, communications director at the Washington State Liquor Control Board, says. “We operated without any federal guidance other than to tell us it was illegal.”

Patchy Oversight

State officials in Colorado, Washington and Oregon -- whether they serve on the liquor control boards, at the revenue department or in public health -- say they are doing the best they can given the circumstances. The Food and Drug Administration -- the federal agency responsible for regulating everything from herbal supplements to prescription medicines -- offers no guidance on the subject of weed. In fact, there has been little scientific research on marijuana due to a federal ban on the substance. This absence of research and federal guidance makes it nearly impossible to set the sort of evidence-based policies that are considered the gold standard within public health.

But so far, those states that have legalized both medical and recreational marijuana have taken an inconsistent approach -- in Oregon, medical marijuana remains largely unregulated even while officials put such careful thought into shaping the recreational program. While recreational users may soon enjoy access to weed that has been proven safe with a clearly labeled potency, cancer patients could be left with zero regulations governing the marijuana they buy.

“Medical marijuana in Oregon is largely unregulated -- it's untracked, untraceable and generates very little revenue,” the Oregon Liquor Control Commission's Towslee says.

This was also the case in Washington until Governor Jay Inslee signed a bill last month that will require the state’s medical dispensaries to abide by the rules that currently govern recreational outlets beginning in 2016. Before this fix, an explosion of rogue medical dispensaries threatened to undercut the state’s legitimate recreational stores.

“I could hit a baseball from where I'm standing and hit five of them [medical marijuana dispensaries],” Smith says.

There have been other missteps along the way. When recreational marijuana was first legalized in Colorado, health officials underestimated the popularity of edibles and failed to develop labeling standards or limits on how much THC, the active ingredient within marijuana, should be permitted in weed-infused food or drink. Though it’s nearly impossible to overdose on marijuana, THC-infused edible products were implicated in the deaths of two people soon after legalization.

Colorado has since committed $9 million to support research on pressing questions such as whether medical marijuana can be used to treat post-traumatic stress disorder. Last Friday, a science advisory committee in Oregon held its first meeting to prepare the state to begin accepting applications for retail sales of marijuana in January 2016. Its members will review research and suggest policies for recreational marijuana sales.

“It’s so bizarre because the states are doing the job of the federal government,” Canna Law Group's Bricken says. “They’re in the driver’s seat -- there’s no question.”

Kartina Hedberg, state health officer at the Oregon Public Health Division, says the first question the advisory group will tackle is what constitutes a serving size of marijuana. Colorado and Washington have both chosen to call 10 milligrams a serving size, but it’s really open to interpretation.

‘A Grand Experiment’

Back at Analytical 360, Brown had to do extensive research when he started the lab to create methods for measuring the marijuana's potency and searching for contaminants. Now, he advises state health officials and the liquor control board on these tests. He has noticed a wave of new clients who are eager to comply with the latest requirements -- and has watched the overall quality of marijuana samples improve over time.

“Once people have the ability to look at data on their product, it gives them a baseline so they can actually improve it,” he says.

Still, he points to a computer screen and admits there are “crazy outliers” in some of the test results reported from certified labs and published by the Cannabis Transparency Project, since not all certified labs in Washington use the same methods.

Towslee says there’s a similar problem in Oregon. “We just need to get that under control -- we need to have consistent testing of these products so the public knows exactly what they're getting,” he says.

It's a problem that appears to have no simple solution.

“This is a grand experiment,” Towslee says. “It’s going to be a long time before everything gets sorted out.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.