Market Volatility, Balance Sheet Surprises Raise Risk Of Bumpy Fed Pivot

The Federal Reserve is expected to approve plans next week to reduce a nearly $9 trillion balance sheet that ballooned as part of its efforts to fight the pandemic recession, in a process U.S. central bank officials expect to run without a hitch.

The past week may point to a bumpier ride ahead, with analysts noting an unexpected, nearly $500 billion shift in the Fed's balance sheet driven by factors beyond its control and volatility in stock and bond markets as signs the central bank's pivot to tighter monetary policy may not run so smoothly.

Yields on the government bonds most sensitive to expectations for how the Fed may cull its balance sheet have swung wildly in the past week, and measures of fixed-income market volatility are near their highest since the onset two years ago of the coronavirus pandemic, which set the central bank on its bond-buying spree in the first place.

In particular, a nearly 9% drop in the S&P 500 index over the past month may show a coming hit to household wealth that quickly translates into lower consumer spending, said Steven Blitz, chief U.S. economist at TS Lombard. He noted that changes in asset prices are a key and perhaps increasingly important way monetary policy can influence economic activity and inflation.

"The tie between consumer spending and equity market performance has grown tighter over the years," Blitz said, as more households invest and holdings increase among the age groups most likely to buy higher-priced durable goods.

If markets continue to weaken, consumers will "sharply contract spending by the end of this year, possibly sooner," he said. "This economy needs a 'buyers strike' to flip into recession, and weak enough equities could stress household balance sheets enough to set one off."

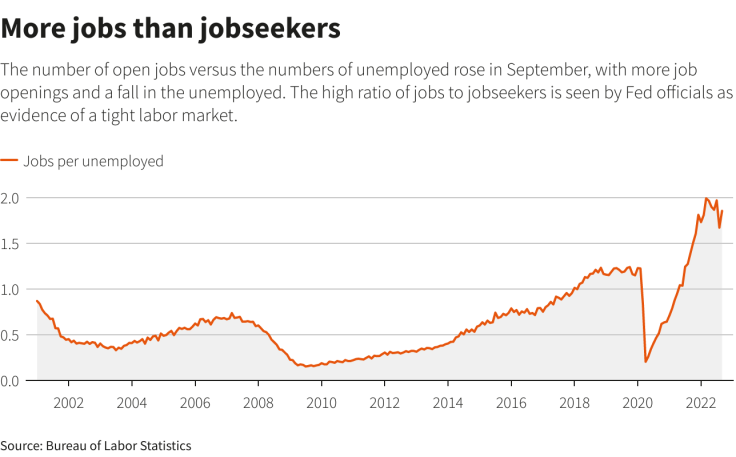

Graphic: Unemployed to job openings -

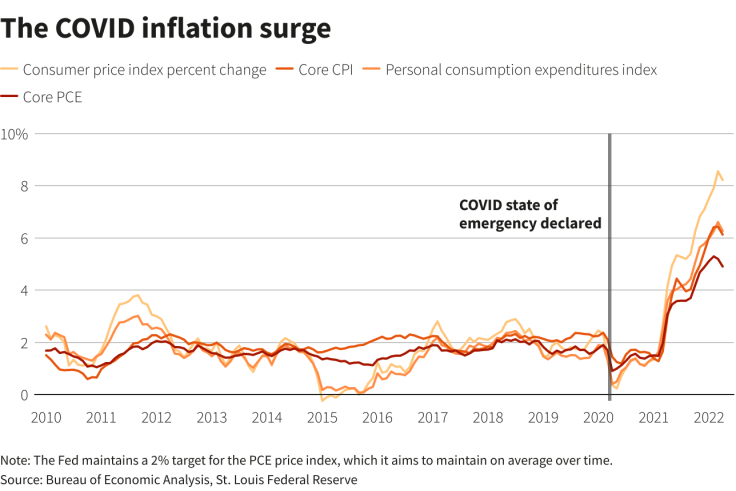

The Fed wants demand to weaken, but in a measured way that is enough to cool inflation - currently at more than 6% using the central bank's preferred measure and more than 8% based on the widely cited consumer price index - while leaving a strong job market largely intact.

Through asset values and other channels - rising mortgage interest rates may already be cooling housing prices, for example - the Fed hopes inflation can be brought down to the central bank's 2% target.

TWO-FISTED TIGHTENING

The challenge is clamping down on the economy without breaking it.

U.S. gross domestic product fell 1.4% over the first three months of the year, the Commerce Department reported on Thursday, but the decline was driven by a drop in government spending on pandemic programs, falling inventories, and a spike in coronavirus cases that has since eased. Personal spending remained strong and imports grew.

New inflation-related data to be released on Friday for March is expected to show little relief from the trends that have pushed the Fed from nursing the economy through the pandemic to taming the excesses of its reopening.

Graphic: The COVID inflation surge -

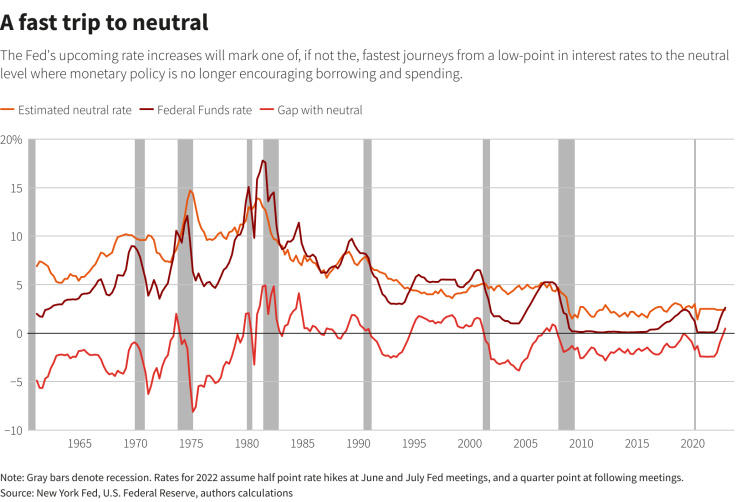

The Fed is about to tighten monetary policy in a two-fisted way that has never been attempted with such intensity - raising interest rates in larger, half-percentage-point increments for the first time in 22 years, shifting in what may be record time from interest rates meant to boost the economy to a "neutral" stance, and allowing its balance sheet to shrink by as much as $95 billion per month likely beginning in June.

The central bank's policy committee will meet on Tuesday and Wednesday and is expected to approve both a half-percentage-point rate hike and the upcoming balance sheet reductions. The Fed raised its policy rate by a quarter of a percentage point at its last meeting in March.

Plans to trim $60 billion per month from the Fed's holdings of U.S. Treasury bonds and up to $35 billion per month from its holdings of mortgage-backed securities were outlined in the minutes from the Fed's March meeting, and the announcement of formal approval and a start date is not likely on its own to have much impact.

But there is still the potential for stress in an economy that may be facing more of it than expected between the war in Ukraine, new coronavirus lockdowns in China that could slow improvements in the global flow of goods, and a fast-moving Fed.

Graphic: A fast trip to neutral -

TREASURY WILDCARD

The impact of the changes to the Fed's balance sheet will to some degree depend on decisions outside its control, including how commercial banks and large money market funds manage their own businesses, and how the U.S. Treasury finances government deficits.

As the Fed becomes a smaller player in the government bond market, Treasury's decisions to sell more long-term or short-term securities could influence interest rates and the economy in different ways.

"The key input is how the Treasury Department alters its financing strategy in response to the Fed stepping back," said Ed Al-Hussainy, rates strategist with Columbia Threadneedle.

Next week will bring developments of consequence on both fronts: The Fed will roll out its balance sheet playbook and the Treasury will unveil its debt supply plans for the next three months. How well the two mesh is an open question.

As Al-Hussainy noted: "The Fed accounts for less than 20% of Treasury demand while the Treasury Department accounts for 100% of supply."

Citi economist Matt King noted the potential for surprises. While it was deep in the weeds of the Fed's operations, an apparent rush of tax payments to the Treasury Department's account at the central bank last week, coupled with banks' use of a technical Fed program, in effect pulled $460 billion out of the financial system and, King said, possibly caused some of last week's stock market volatility.

Some of that may reverse, he said, but "the trajectory remains clear," he wrote. Central banks globally are pulling back, and the impact is "not fully priced in to risk assets."

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.