Mars Methane Mystery: Is There Solid Proof Aliens Caused Spike?

When NASA’s Curiosity rover recorded a sudden spike in methane gas on Planet Mars a few months back, scientists naturally became very excited.

According to The New York Times, NASA’s Curiosity rover was able to detect one of the highest levels of methane gas in the Martian atmosphere since 2013 at 21 parts per billion. Methane gas plays an important role in the research of life in Planet Mars since the gas is associated with organic microbes often found underground on Earth.

The excitement was short-lived, however, because as quickly as it appeared the methane gas also disappeared just as fast.

“A plume came and a plume went,” Paul Mahaffy, from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, said during a presentation in Bellevue, Washington.

“The methane mystery continues. We’re more motivated than ever to keep measuring and put our brains together to figure out how methane behaves in the Martian atmosphere,” Ashwin Vasavada said in a statement from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), which handles Curiosity.

Some thought the research on the mysterious methane gas appearance ended when levels went down once more, but a recent report said that scientists are now closer to finally figuring out what really happened.

According to Phys.org, a new study conducted by the team of Dr. John Moores, an ANU Visiting Fellow based at York University in Canada said they might be able to figure out what really happened during the methane spike last June. Moores is leading the latest study on the phenomenon although scientists had been speculating for quite some time now what the source could either be from living microbes or just natural occurences within the planet.

"This new study redefines our understanding of how the concentration of methane in the atmosphere of Mars changes over time, and this helps us to solve the bigger mystery of what the source might be," Moores said.

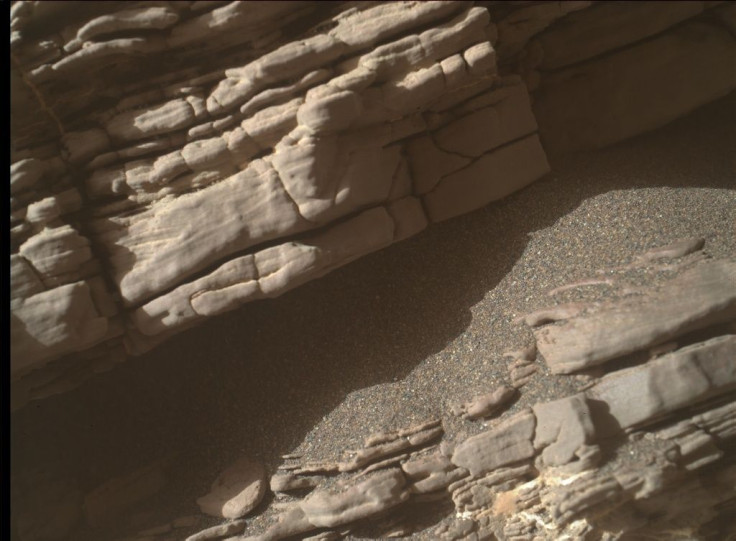

Using data collected by the satellite ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter and the Curiosity rover that studies the Martian surface samples, Moores’ team was able to get a better estimate of the methane levels on Mars. Based on their research, it was deemed that the gas coming out the Martian surface could come from an ancient lakebed that’s around 3.8 billion years old.

"Some microbes on Earth can survive without oxygen, deep underground, and release methane as part of their waste. The methane on Mars has other possible sources, such as water-rock reactions or decomposing materials containing methane," Moores’ co-researcher and ANU Research School of Earth Sciences Professor Penny King said.

Although there is no clear indication of where the methane gas actually came from, the researchers claim that it’s only a matter of time before they can give something definite.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.