Medical Residents Use Apps And Activism To Fight Hospitals For Bigger Salaries, Better Benefits

Somewhere along the path to realizing his dream of becoming a primary care physician, Nathan King realized that he was spending way too much money on parking. The 29-year-old is finishing his third year of an internal medicine residency at University of California – Irvine and spends a lot of his time at UC Irvine Medical Center.

The hospital offers residents a $101 monthly parking pass, but King couldn’t find time in his busy schedule to show up to the parking office so he wound up paying the much higher $12-a-day visitor rate on most days that he saw patients. He earns precisely $55,807 a year.

“It was killing me,” he says.

Last year, King began commuting by bicycle to avoid the hefty parking fees. That’s just one example of how he has struggled to balance the demands of his medical training with those of a growing household. He and his wife, who does not work, are also raising two kids – a 2-year-old daughter and a 3-month-old son.

“The place we are in life is not really what they built residency training for,” he says. “I'm defying a lot of norms by having a family.”

When he finishes his training, King will earn a handsome reward: the average family physician in the U.S. makes about $176,000 a year. But in the meantime, his student loans combined with family demands and the high cost of living in the greater Los Angeles area make for a daunting financial challenge, and he thinks his residency program should do more to help.

He's not alone -- lately, increasing numbers of medical students and residents are seeking ways to introduce transparency to the process of finding and completing a medical residency. Many of them are joining forces to advocate for better treatment by the hospitals that employ them. Meanwhile, those hospitals earn millions of dollars from the government for training a few hundred residents a year through an arrangement that critics have said is oqaque and misguided. Residents such as King are asking that more of this money be returned to them.

While their college friends join tech companies and sign up for startups offering their employees free transportation, complimentary beer and on-site dry cleaning, medical residents such as King slave away at teaching hospitals that dictate far different terms of employment to doctors-in-training. Unlike their peers elsewhere, many residents cannot negotiate their salary and benefits even while some programs require trainees to work up to 16-hour shifts and live within 30 minutes of the hospital. Oftentimes, they don’t even learn the full terms of employment until after they’ve committed to train at a specific program.

“Residents have very little power or control over any aspect of the training,” Dr. Alex Pulst-Korenberg, a first-year resident in emergency medicine at University of Washington in Seattle, says. “There’s no other profession in the world where somebody will sign a contract that's non-negotiable, not knowing what city they're going to be in, not knowing what their salary is going to be and not knowing their benefits.”

An Imperfect Match

On Tuesday, medical students sent out their first applications through the National Resident Matching Program for positions that will begin next year. The selection process works like this: students rank their top programs and the service orchestrates a “match” with program directors who have ranked students. All students learn where they’ve placed on the same day (the next “Match Day” is on Friday, March 18). Students often feel that their entire future hinges on the algorithm that directs the chaos of this high-pressure process.

“You open an envelope on Match Day and you're told where you’re going for the next five years of your career,” Dr. Akshay Sanan, a third-year resident in head and neck surgery at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, says. “So it's a very stressful process.”

It’s also expensive -- the average student pays about $6,000 to apply to and interview at their top programs, a bill that comes as these students each struggle to manage roughly $180,000 in debt . Sanan, who is in a particularly competitive specialty, applied to nearly 50 programs and visited more than 20 campuses before settling on his decision.

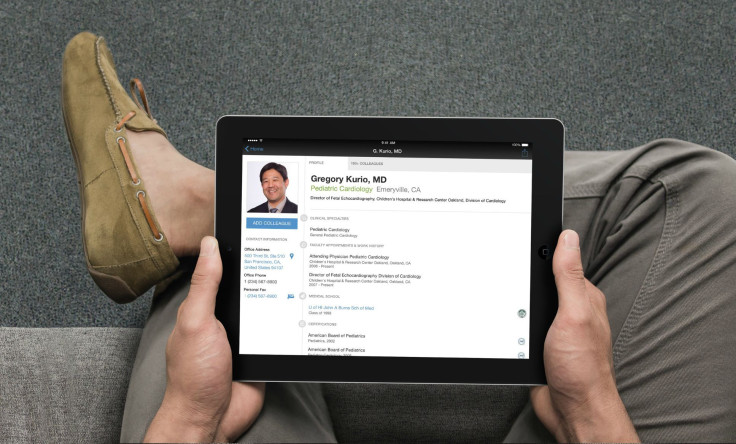

But much like choosing a college, it’s hard to know what life is really like in a program during a visit. To get a better sense, many residents have turned to a new Yelp-like tool called Doximity that allows doctors to rate their residencies and state which programs they think are the best in their specialty. Nearly 40,000 reviewers have posted reviews and ranked programs on schedule flexibility and work hours through a five-star system.

“It's the stuff on the fringes that can make life miserable for residents -- it's how much call they have to take, whether they get time off when they need it,” Dr. Nate Gross, co-founder of Doximity, says.

Applicants can also see the percentage of residents who pass their board exams at each institution – information that Gross says was surprisingly difficult to obtain, and which still isn’t available for some specialties such as anesthesiology. Before Doximity, there was no clearinghouse for qualitative and quantitative information on these programs. The company says that last year, 75 percent of U.S. medical students used the tool during their search.

Abhi Aggarwal is completing his fourth year of medical school at George Washington University Medical School in Washington, D.C. He recently logged on to Doximity to find diagnostic radiology programs and used the rankings to create a spread that included several “safe schools” as well as more competitive programs. Out of the 140 students in his class, he estimates that at least 90 have used Doximity to scout out their options.

The 25-year-old plans to apply to 60 programs and has set aside about $1,500 for application fees and up to $10,000 for travel expenses to visit programs. He says it will be a relief to finally make some money after compiling student debt through four years of undergraduate school and four years of medical school.

“The problem is that after investing for eight years, I really have no choice,” he says. “My alternative is really just to drop out, I guess, and do something else and never really make a good return on my investment.”

Bargaining for Rights

Even after they’ve landed their dream assignment and begin earning a paycheck, many residents still find the conditions within their program to be less than desired. Residents at some hospitals have formed collective bargaining units to address issues about salary, benefits and working conditions – and they are making some headway.

“It's pretty safe to say almost no residents look at the benefits package when they make their decision because their education and training is their top priority but it does have a significant impact on your life,” Pulst-Korenberg says.

Earlier this year, residents in New York City won a $1,000 bonus. Residents at Rutgers University in New Jersey earned a $20 meal credit at the hospital cafeteria when they work overnight or extended shifts and a $50 increase to an annual stipend that they can use to buy books or technology. Residents at the University of Washington are currently negotiating for dramatic salary increases of about 40 percent above current levels and $5,000 per year for childcare expenses.

At UC-Irvine, King is leading a group of his peers in closing the school’s first-ever labor contract with medical residents. He’s working with the Committee of Interns and Residents (CIR), which is the largest union in the country for residents, fellows and interns. The group represents nearly 12,000 members across six states including California, Florida, New York and Massachusetts.

“Every year, we have an influx of interns, residents and fellows and they are the youngest group of employees at the hospital. Even the custodial person has been there longer,” Dr. Hemant Sindhu, president of CIR, says. “When you're the lowest person on the totem pole it's really hard to make your voice heard whether it's an issue of patient safety or advocating for yourself.”

But the UC-Irvine negotiations have dragged on for 14 months. Samuel Strafaci, director of labor and employee relations, says that’s partly because compiling a simple list of all the different benefits offered by the school’s many residency programs was “like herding cats,” but he expects the discussions to wrap up soon – perhaps as early as their next meeting on September 29.

While many issues have already been resolved, the parties still disagree on a $5,000-a-year housing stipend. King’s program requires him to live within 30 minutes of UC Irvine Medical Center so that he can respond quickly when he is on call. But the average rent in surrounding Orange County, California is $1,807 a month.

Strafaci says offering a stipend to UC-Irvine’s 700 residents would cost the university about $3.5 million a year. Instead, the administration would prefer to offer subsidized housing rather than re-negotiate a new stipend with each contract renewal.

And as for reduced or free parking – King may have to stick with his bicycle.

"There is no cost-sharing or free parking for any of our employees,” Strafaci says. “That’s been our position and that's been one of the sticking points."

King says it has also been hard to recruit new residents to the cause. He says they are at a fundamental disadvantage as compared with other work groups because turnover is fast, and residents have a strong incentive to defer to program directors and hospital administrators.

"Your career gets launched from your residency," he says. "Why would you jeopardize your career for something like a $5,000 housing stipend? For a lot of people, it's just not worth it."

Making A Case For Patients

Residents argue that improving their own working conditions will help patients, too.

Many residents have begun to ask hospitals to set aside a fund for them to purchase equipment or implement changes that they think are important. At many hospitals, these funds are billed as patient safety initiatives that could reduce hospitalizations or cut back on infections.

At Brookdale Hospital in Brooklyn, New York, residents noticed that doctors were performing frequent catheterizations for patients who needed their bladder emptied but did not require a permanent catheter. However, physicians had no way of telling whether the patient actually needed their bladder emptied before the procedure and every catheterization puts a patient at risk for acquiring an infection. So residents used money from a patient care fund to purchase bladder scanners that could tell physicians whether enough urine had built up to merit the procedure.

Los Angeles County in California maintains a $2 million fund for its residents, one of the oldest and largest in the country, with the University of Southern California Medical Center and the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. Residents at the University of California, San Francisco have access to a $50,000 fund through the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center and a $100,000 fund through the San Francisco General Hospital, which they have tapped to buy a PlayStation for pediatric patients and taxi vouchers for pregnant patients.

To the extent that these programs reduce a patient’s chance of returning to the hospital – or boost a child’s mood as they recover from surgery – improving the fate of residents at hospitals nationwide may also be in patients’ best interest.

And though Doximity is off-limits to anyone except medical students, residents and physicians, the transparency it lends to the selection process could also bring more positive outcomes. Students with more access to information may find it easier to choose the right program, and ultimately be happier and more successful as physicians. Or, teaching hospitals and residency programs that feel competitive pressure when their statistics are laid bare might work harder to improve programs.

Even with this year’s gains, Sindhu of CIR says he would still like to see more residents serving on committees and helping to make decisions alongside hospital administrators, pointing out that this is valuable workforce training.

Back at UC-Irvine, King says he has two younger siblings who were once considering becoming doctors. But after watching him struggle through the process, they’ve both decided to become nurses instead.

“The wonderful thing about nurses is, they're all unionized and they advocate for their needs so well," he says.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.