Meet The Man Who Runs New Orleans’ Entirely Privatized (And Controversial) City Surveillance System

“Forgive me if we’re in the middle of this and I have to move my attention to the crime cameras. It’s just the way of life around here.”

Today, like most days, Bryan Lagarde is standing in his “incident monitoring center,” a small, darkened room inside 1308 Dealers Ave., a squat one-story building in an industrial neighborhood on the west side of New Orleans. The room is filled with big-screen TVs and computer monitors, all broadcasting live video feeds from 1,500 high-definition cameras placed all around the city. Lagarde is a 45-year-old New Orleans man, business owner, former police officer and, now, something of a surveillance-meets-criminal-justice vigilante.

Despite its high crime rate, New Orleans does not have a city-backed surveillance system. So four years ago, Lagarde decided to launch his own. “We said, ‘Merry Christmas. Guess what? We just created a crime camera system,” Lagarde says. “We recognized that it needed to be done.”

The result is Project NOLA, perhaps the country’s first and most extensive private surveillance network, run, improbably, by one man and a ragtag group of volunteers.

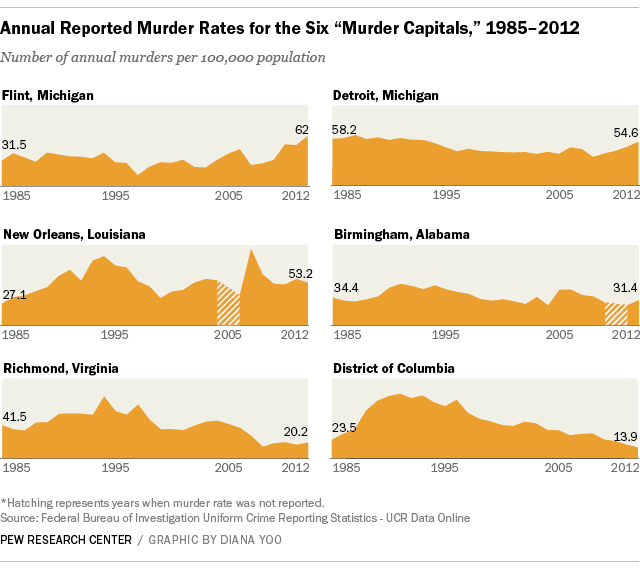

Ten years after Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans remains rife with crime, poverty and a severely short-staffed police department. Zoning laws keep the city segregated in both economic and racial terms. City murder rates consistently rank among the highest in the country. It is, in many ways, a tale of two cities: Those who have, and those who have not.

In recent years, wealthier residents have developed privatized systems to make New Orleans more liveable. For instance, one entrepreneur recently created an app to let people instantly summon up a local police force. Project NOLA follows suit: One wealthy resident created a system that, in many ways, is more efficient than anything the city government has created.

This is how it works: New Orleans residents who have chosen to participate install a surveillance camera on their home or business. The cameras must face toward the street and broadcast a high-resolution feed. The videos feed directly to Project NOLA’s headquarters. Lagarde says that those who host a camera are also given the username and password, and can access the videos whenever they'd like.

From there, the video feeds essentially serve two functions.

First, the feeds complement Lagarde and his team's monitoring of police radio. When Lagarde hears police dispatchers mention a gunshot, stabbing, home invasion or other serious crime on a certain block, Lagarde will drop everything he’s doing to see if Project NOLA has a camera in that area. If there is a camera nearby, he’ll put the video feed onscreen, and scan the area to see if he can locate a suspect. If he can, he’ll call the police dispatcher’s command desk to assist with any visual information.

Tyler Gamble, communications director for the New Orleans Police Department, confirmed in an interview that, while there is no formal relationship between Lagarde and police, Lagarde is routinely in touch with police dispatchers to provide information. “All of our operators in our command desk know him, and we allow them to relay that information when there’s a crime in progress,” Gamble says.

Providing Valuable Evidence

The second function of the video feeds is to serve as evidence, after the fact, for detectives and prosecutors. “We take a case that would otherwise be unsolvable, and make it an 'A' case,” Lagarde says. “Some videos we provide show the perpetrator going into a house with the gun in their hand and blood on their shirt. You can imagine what we do for some of these cases.”

Lagarde says he’s “lost track” of how many cases have used Project NOLA video streams, but he estimates his team of three handles 20 felony incidents per week. Last year, he says, the system dealt with 1,000 emergency responses, and helped investigate more than 50 homicides. Lagarde points to several ongoing investigations with the New Orleans Police Department that are using video evidence obtained by Project NOLA cameras.

Christopher Bowman, the counselor to the New Orleans district attorney, confirmed in a brief interview that Project NOLA cameras are routinely used in criminal investigations. “We’re a big office,” he says. “We deal with a lot of cases. I know the cameras have been used.”

Earlier this year, New Orleans police launched its own program, SafeCam, to collect surveillance video. But unlike Project NOLA, the SafeCam initiative is merely a database of the locations of 2,500 registered cameras around the city. The footage is recorded by individuals or businesses and stored locally. According to Gamble, it’s a “growing” program and used by detectives so they “know who to contact if we need the footage.”

“The way we see it, there is no competition between SafeCam NOLA and Project NOLA,” Gamble says.

Gamble says the New Orleans Police Department tried to get Lagarde to hand over his database of registered cameras, but Lagarde refused, citing privacy concerns. “Our first priority is actually not crime abatement,” Lagarde says. “It’s to protect the privacy of those who participate by giving us access to their camera.” That access, Lagarde says, costs users $10 per month, or $96 per year. He has registered Project NOLA as a nonprofit organization, and says the program earns less than $100,000 in revenue per year.

'Crime Rate Has Plummeted'

Lagarde worked as a New Orleans patrol officer from 1993 to 1996, when he was promoted to an economic crimes investigator. His specialty was white-collar crime and video surveillance. In 1998, he left the New Orleans Police Department to start CCTV Wholesalers, a small business that sells video equipment, including cameras and mounts. He continues to operate CCTV Wholesalers, but now, on his LinkedIn page, he describes himself as a "criminologist, social entrepreneur, [and] former police officer" who "created America's largest HD networked crime camera system."

Residents who have enrolled in Project NOLA are happy with the program. They say crime rates are down in their neighborhoods and the program acts as a deterrent. Skip Gallagher, a chemistry professor who lives in the city's Algiers Point neighborhood, installed the cameras after his neighbor Harry "Mike" Ainsworth was gunned down in the street while trying to prevent a carjacking in 2012, a case that received national attention.

About 100 of Gallagher's neighbors followed suit, all enrolling in Project NOLA. “Some of the long-term criminals who felt comfortable robbing people” are now behind bars, Gallagher says, noting that the “crime rate has plummeted.”

Another New Orleans resident, Eric Songy, says he’s enrolled two cameras in Project NOLA -- one on his garage, and one on his front door. “It's amazing that [Lagarde] has built it up to the level it is,” Songy says. “I've had a lot of admiration for what he's done.”

Asked if he was concerned that one man had access to hundreds of cameras around city neighborhoods, Songy was unfazed. “He doesn’t have time to spy on people around the city,” Songy says. “He's staying focused.”

He adds, “One of the beauties is that it's not controlled through the city.”

Songy says that people in New Orleans have been deeply distrustful of a city-sponsored police camera system ever since Ray Nagin, the disgraced former mayor of New Orleans, was convicted on corruption charges involving a multimillion-dollar camera system that never materialized. That failure came at a troubling time -- the post-Hurricane Katrina period, when crime rates were spiking.

A decade after Katrina, the city's murder rate remains high. “Just as worrisome, the rise in deadly violence comes as the number of NOPD homicide detectives is at its lowest in five years,” NOLA.com reported recently.

Lagarde says that a shrinking New Orleans police staff has made Project NOLA ever-more important.

“As we lose more and more police officers, our role has shifted dramatically,” Lagarde says. “We’ve gone from simply packaging up the video to, frankly speaking, if we’re not watching the video, a lot of times nobody is going to.”

'He Frequently Tries to Act Like [A Police Officer]'

This is where relations with the police department have gotten somewhat uncomfortable. Gamble, the police spokesman, says that while the police appreciate all the help they can get, Lagarde has overstepped on a number of occasions.

“I don’t want to downplay his contribution to giving us important footage,” Gamble says. “But there are a lot of issues to be worked out.”

Gamble adds, “He’ll watch his video cameras and he’ll listen to feeds of the police scanners. And then he’ll call the command desk and get someone to try to give him information.” Gamble says Lagarde has even tried to re-route officers to a particular scene, and called schools to urge them to go into lockdown after something he saw on a video feed.

“The trouble is, he’s not employed by the NOPD and he’s not a law enforcement officer,” says Gamble. “But he frequently tries to act like one.”

Lagarde acknowledges that he and his team often take a pro-active role. “We do it because no one else is doing it,” Lagarde says.

“Honestly, I would love for someone else to bear this cross. The police should be doing this. But if we don’t, the question is, who would?”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.