Meet Practo, An ‘Uber For Doctors’ That’s Revolutionizing Healthcare On The Indian Subcontinent

BANGALORE -- India’s smartphone revolution has made ordering a pizza or even a gourmet meal a cinch. Finding a trusted doctor when your child is sick and your regular physician is away, however, would normally take a lot more than the 30 minutes it takes to get a slice in hand. But one startup is looking to change that. Bangalore’s Practo Technologies Pvt. Ltd., an online doctor search provider, wants to do for India's healthcare what Flipkart, the country’s largest e-commerce company, is doing for online shopping.

India has the largest base of Internet users after the U.S. and China, and yet, even for its 50 million to 60 million urban, middle-class households, which can by and large afford to pay for medical care, finding the right doctor in time can be hit or miss. Long waits are commonplace and when tests are needed, running back and forth from the diagnostics centers to the doctor and personally ferrying paper records is the norm. Vignesh Muralidharan, who just quit a tech job to turn entrepreneur in the southern Indian city of Chennai, developed a severe ear infection and needed a specialist. “I’d never been to an ENT specialist before, and Practo had user reviews, doctors’ reviews; it was pretty handy.” The 24-year-old engineer gave Practo’s e-booking system high marks. “That made my life easier, I didn’t have to call anyone,” said Muralidharan, who has the Android version of the app on his Google Nexus 5.

In India’s fragmented and low-tech healthcare market, Practo founder N.D. Shashank saw both a gap and an opportunity. “I faced an anomaly,” he recalled about a time in 2008 when, while looking for digital records for a second opinion on his father’s knee surgery, he was forced to take pictures of paper records and manually upload them to a consultant in the U.S. “I was meeting one of the top orthopedic surgeons, the best hospital and the best doctor, but the technology he was using (paper records) was average,” said Shashank.

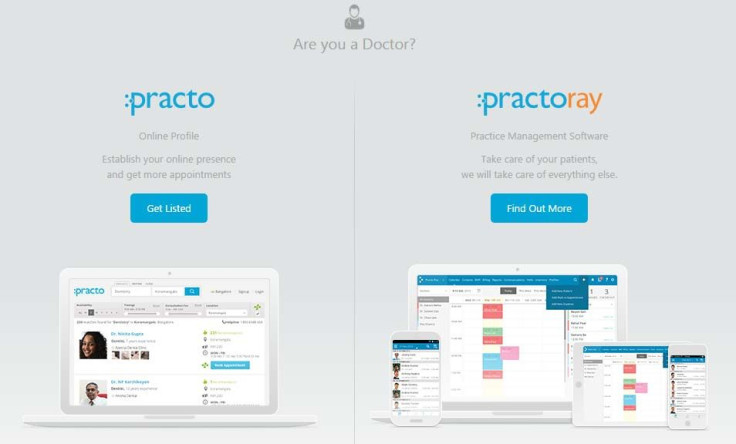

That inspired him to create a digital “health account” that could be easily accessed and shared. He first built Practo Ray, clinic-management software that doctors use on a pay-as-you-go basis. The success of that cloud business landed $4 million in Practo’s kitty from Sequoia Capital in 2012, which allowed Shashank and co-founder Abhinav Lal to build Practo Search, the consumer oriented doctor-search product. Via a mobile app or website, Practo Seach allows users to search for general physicians or specialists, narrow the selection down based on factors such as experience of the doctor, location, time slot and so on.

Appointment booking is integrated into the search product for those doctors who are also using Practo’s clinic-management software. On selecting one and entering basic details such as name, reason for the appointment, email ID and mobile number the user receives a verification code, which can be used to complete the booking.

Dual Revenue Streams

Most people in India spend out of pocket on health care. Total expenditure on health in the country as a percentage of gross national product was about 4 percent in 2013, according to the World Health Organization, and public spending accounted for less than a third of that.

10 million people, mostly in India, currently use Practo’s search engine each month to find healthcare professionals who can perform everything from a root canal to open-heart surgery. Over two-thirds of that traffic is via smartphones. The alternative, for the vast majority, is to walk into a local dentist’s clinic or, for the heart ailment, get a reference from a general practitioner.

Practo makes money in two ways. As more people use the search engine, it becomes an increasingly attractive place for clinics to buy ad space for “information cards” about doctors and the services they provide. This is much like the ads that show up in a Google search, but India’s rules don’t allow individual doctors to advertise themselves. Their clinics, however, are allowed to place these “fact-based” banners or other adverts.

This business is growing “incredibly fast,” Practo said in an email. For now, however, the clinic management software is the main revenue driver. Doctors pay a recurring annual fee of between 12,000 rupees ($189) and 36,000 rupees ($566) for using the software as a service. Of the 140,000 or so doctors listed on Practo, about 35,000 pay to use the clinic-management software. Listing on Practo for the doctors is free and and Practo charges no fee for appointments booked via the service.

In the longer run, the search ads business is a bigger market, at about $2 billion currently in India alone, while the clinic management software-as-a-service business addresses a market of about $250 million presently, according to Tarun Davda, a director at Matrix Partners India in Mumbai. Matrix Partners led a $30 million investment alongside early investor Sequoia Capital, in Practo’s second round of venture funding in February. Practo is strongly rumored to be in talks with Russian billionaire Yuri Milner’s DST Global and Google Capital for its next round of funding, which could see it raise as much as $60 million. Shashank declined to comment.

India’s overall healthcare market is expected to double to about $160 billion in 2017 from about $79 billion in 2012, according to an estimate by the India Brand Equity Foundation. It’s projected to reach $280 billion by 2020. Private providers account for an estimated 81 percent of the market today.

Practo touches 140,000 doctors in 35 cities in India and is looking to rapidly scale up. In parallel, it has already expanded to Singapore and Philippines and expects to push further into Southeast Asia and soon Latin America, Shashank said. “We’re today helping consumers find doctors, but that is only one part. There are diagnostics centers, pharmacies and there are preventive elements such as spas, fitness centers, yoga centers and gyms,” which he expects will all eventually be on the Practo’s marketplace ecosystem. “Today there are doctors, consumers and data. We can clearly connect up several parts of this ecosystem,” Shashank said. “If you think you have the flu and are worried it could be H1N1, you should be able to ask for a test at your doorstep.”

Cloud, Security By Amazon

As for security and patient privacy, Practo’s data center is hosted on Amazon.com Inc.’s cloud. Its products “comply with the most stringent standards globally including but not limited to HIPAA,” the company said, referring to the U.S. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which sets standards for healthcare data security.

India doesn’t mandate HIPAA compliance, but a combination of data privacy rules and regulations related to management of electronic health records apply. These will likely get a boost from the federal ‘Digital India’ umbrella program, where connecting up the country’s health services is an important aim.

Investors including Matrix believe that Practo has a strong chance of long-term success because it is striving to be an end-to-end marketplace, unlike ZocDoc, a startup that does appointment bookings in the U.S., or Guahao, which functions similarly, as well as Chunyu, which does on-demand remote consultations, both in China. “Given that Practo operates across all aspects of the healthcare ecosystem, it has the unique opportunity to capture a disproportionate value of the overall pie,” Davda said, in an email.

Shashank declined to comment on specific revenue numbers, but Davda added the company was growing at “5X annually.”

Practo, however, like many startups, is a work in progress. Complaints from users, based on their comments on Practo’s Facebook page, include canceled appointments, doctor mismatches, hospitals denying appointments and even inaccurate information being thrown up in searches. “The idea is great but the delivery poor,” wrote Sathyaki Nambala, a cardiac surgeon himself at a well-known chain of hospitals in India, in a 1-star review of Practo on its website, out of a possible five. “Doctors are listed randomly with the wrong specialty assigned. For example if you look up cardiac surgeons all the names that pop up are those of cardiologists. If you look up valve replacements, physicians are listed as doing the procedure,” wrote Nambala in the review earlier this month.

In an email to IBTimes on Wednesday, a Practo spokesperson refuted the claim made in the post -- described by him as "at minimum an exception of (sic) not completely inaccurate" -- and said that Practo does "not classify doctors randomly" and that it follows the Medical Council of India's classification guidelines.

With luck, over time, there will be fewer such instances and more happy users such as Vignesh. Otherwise, there’s only so much real estate for an app on a smartphone. “When you are really in pain and you don’t know where to go, it is pretty good for that,” he said.

Note: This story has been updated to include a statement from a Practo spokesperson in the penultimate paragraph.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.