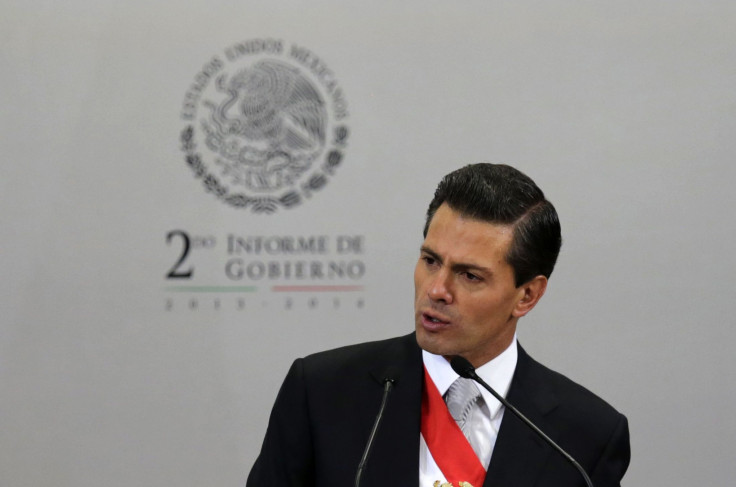

Mexico's Economy: President Peña Nieto Promised Sweeping Reforms, But Corruption Accusations Have Stalled Growth

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto marked the halfway point of his six-year presidential term Wednesday with his third State of the Union address, an opportunity he used to highlight his signature plan to dramatically boost Mexico’s economy. But many Mexicans say Peña Nieto's reforms have fallen short of expectations, hampered by corruption and global economic uncertainties.

Peña Nieto has pushed through roughly a dozen bold reform packages for the energy, telecommunications, finance and education sectors -- among others -- since he assumed the presidency in late 2012. Mexican officials originally estimated the changes could net 4 to 5 percent annual growth for the country. But three years later, growth figures remain modest: The economy expanded by 2.1 percent in 2014 and is projected to grow around 2.3 percent in 2015, according to the Bank of Mexico’s surveys of private economists in August.

Turmoil in global markets spurred by uncertainties over China’s economy hasn’t directly affected Mexico as severely as it has some of its South American neighbors that rely more heavily on Chinese trade. But the slump in global oil prices and weakening currencies in emerging markets has made it harder for Peña Nieto’s administration to rally growth, even though prudent fiscal measures have cut down on inflation and debt.

Those difficulties have damaged public enthusiasm for Peña Nieto and his economic agenda. A survey released Tuesday by Mexican polling firm Parametria found that 63 percent of Mexicans said the president had achieved less than what they expected from him during the first three years of his presidency, with 57 percent saying the economy has gotten worse in the last year. Thirty-nine percent said the economy would get worse in the next year, while 41 percent approved of Peña Nieto’s performance overall. Another survey by polling firm Buendia & Laredo found his approval rating at just 35 percent, as the president has battled ongoing violence and corruption in the country, as well as allegations that his wife purchased a mansion from a favored government contractor.

The next three years will be a major test of whether the Peña Nieto government can successfully implement its economic plan, which so far has seen mixed results. Investors are keeping close tabs on developments in Mexico’s energy reforms: Peña Nieto pushed through a constitutional change in 2013 to open up the oil sector to private investment, breaking up the state-run oil company’s 76-year-old monopoly on the oil sector and opening a host of new opportunities for Mexico to attract foreign funds.

But the decline in global crude oil prices, which began last year, has tempered enthusiasm to invest. Mexico’s first auction for offshore oil assets in July only netted bids for two out of 14 available oil fields. Mexico has been trying to offer additional benefits to oil companies as it prepares for its second auction, set for Sept. 30. But it will also have to compete with Brazil, which is holding its own oil auction just a week later.

Changes to the tax code, which Congress passed in 2013, have helped the government net more revenue to fund the rest of its reform plans. But critics -- particularly business leaders -- have lashed out at the tax reforms for putting higher burdens on those already paying taxes, rather than reining in workers in the informal economy, while keeping economic growth stagnant.

Education reforms have also hit major setbacks. Peña Nieto introduced a plan to overhaul the education sector shortly after coming into office, including teachers’ evaluations, merit-based pay and stronger federal oversight over the system. He touted the plan as one that would transform Mexico in the long run by providing better quality education, fostering innovation and diminishing incentives to turn to crime. But one of the largest teachers’ unions in Mexico put up intense resistance to the plan, launching turbulent protests against teachers’ evaluations. The government is continuing to face off with the union as it tries to implement the new policies.

Many of these reforms still have the potential to pay off in big ways for Mexico’s economy down the line, said Christopher Wilson, deputy director of the Mexico Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center, a think tank based in Washington, D.C. “But it’s a process that takes a lot of time,” he said. “With falling energy prices and other headwinds in the global economy, Mexico’s had a tough economic environment to move through. Unfortunately, on the ground right now, most people don’t feel the positive impact of the reforms, despite strengths there within them.”

The public’s disappointment in Peña Nieto’s presidency won’t necessarily hinder the government’s ability to keep pursuing its economic agenda. But analysts say the administration has fallen short on one key area: Building a robust anti-corruption scheme. Many critics say the administration hasn’t combated impunity aggressively enough. The government earlier this year approved a sweeping anti-corruption system that is still awaiting secondary laws for implementation.

“The government, despite all its talk, not only has not done much to give a tough response to the problems of corruption, influence peddling and the use of power to benefit a few, but it has also shown opaqueness into cases that have come out publicly,” Alfredo Coutiño, Latin America director at Moody’s Analytics, told CNN.

The persistence of impunity has caused mass outrage in cases like last year’s disappearance of 43 students in Mexico who were allegedly killed by drug gangs working in tandem with police. But having a weak rule of law will also severely curtail any economic gains made by the rest of the reform agenda, Wilson said.

“If other reforms create a regulatory framework attractive for foreign and domestic investors alike, but there is no confidence the law will be applied as written, they won’t be worth much,” he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.