As Michigan Fights Flint Water Crisis, Residents Worry Of Bad Air Quality In Metro Detroit

Vicki Dobbins is a resident of River Rouge, the tiny Detroit suburb nestled amid a hulking Marathon oil refinery, two DTE Energy power plants, a U.S. Steel facility, and the Carmeuse lime kiln. In this town of 7,000 people, the dust from nearby factories is enough to cover cars with a thick gray film on some days.

Dobbins says she developed asthma after moving to the area around 2001 to care for her sick mother. She now carries an inhaler in her purse and keeps a medical nebulizer at home to stave off asthma attacks, which have sent her to the hospital. Her ZIP code – 48218 – is one of Michigan’s most polluted, and asthma rates in this area are 50 percent higher than the rest of the state, according to the Detroit Health Department.

“I have to grab myself for air sometimes,” Dobbins says. “It’s very scary.”

As Michigan scrambles to fix the lead-tainted drinking water in Flint, residents near Detroit say they’re fighting a public health crisis all their own. Coal-fired power plants and steel mills in the area are spewing excessive levels of sulfur dioxide, a toxic gas that causes asthma attacks and other breathing-related problems. Federal regulators have ordered state officials to clean up the air, but the state’s work to curb the pollution is in limbo.

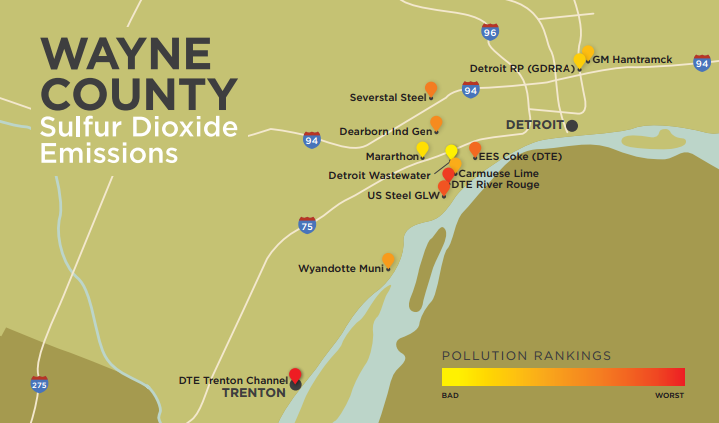

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says portions of Wayne County – including within River Rouge – do not comply with federal air quality standards for sulfur dioxide (SO2), which were recently tightened amid growing concerns about the pollutant’s short-term health effects. The agency in 2013 designated the county and 28 other areas nationwide as “nonattainment,” a decision that requires state governments to develop plans to reduce pollution.

Regulators this week are expected to expand that list as the EPA resumes the crackdown on SO2 sources. The agency is planning to propose designations for nearly 70 facilities in two-dozen states, including eight other plants in Michigan (although some plants may be found to meet the standard or deemed “unclassifiable”). State authorities will have 120 days to respond to the EPA before the agency officially deems the zones nonattainment by a July 2 deadline.

Under the Obama administration, the EPA has used the Clean Air Act to target pollution from a sweep of sources, including electric power plants, oil and gas rigs and vehicle tailpipes. While the agency has moved aggressively to curb planet-warming carbon emissions and smog-forming ozone, the push to limit SO2 has moved more slowly, environmental groups say.

“In some ways, it’s lower-profile,” says Zachary Fabish, a staff attorney for Sierra Club in Washington. “That isn’t to say that SO2 isn’t dangerous; it’s a big problem.”

The EPA in 2010 revised the national SO2 standard to 75 parts per billion during a one-hour period. The agency determined that as little as five minutes of exposure to SO2 could aggravate asthma symptoms or constrict people’s airways, particularly in vulnerable groups such as children and the elderly. Sulfur dioxide also reacts in the atmosphere to form particulate matter, which can cause respiratory disease like emphysema and aggravate heart disease, leading to higher numbers of emergency visits or premature deaths, according to the EPA.

Regulators analyzed which facilities failed to meet the new standards and issued the first round of noncompliance decisions in 2013. But then the work stalled, and the Sierra Club, Earthjustice, the Natural Resources Defense Council and public health groups sued the agency. A U.S. district court decision last March imposed new deadlines on the EPA. Following this week’s batch of notices, the EPA will issue two more rounds in coming years.

Michigan officials say they’re still developing a plan for the EPA to address SO2 emissions in parts of Wayne County. The state Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) missed a federal deadline in April, in part because negotiations with the five major pollution sources took longer than expected. The state did offer a draft plan for public comment last fall, but the EPA said the draft was insufficient, effectively rejecting it.

The state’s SO2 dilemma is playing out as DEQ officials grapple with the poisoned-water crisis in Flint, about 80 miles northwest of River Rouge. The city’s 100,000 residents have been pouring lead-tainted water from their taps for nearly two years, with most unaware of the problem. City and state officials largely dismissed it until late last year, after high lead levels were detected in Flint children. Dan Wyant, the DEQ’s director, resigned in December after a public outcry. Republican Gov. Rick Snyder declared a state of emergency over the issue on Jan. 5; President Barack Obama signed a disaster declaration for Michigan on Jan. 16.

Michigan’s mishandling of the Flint crisis has drawn accusations of environmental injustice. The majority of the city’s residents are black, and many are lower-income. The overlap of public health risks and nonwhite communities isn’t confined to Michigan: Nationwide, black and Latino people make up nearly half the population in “fenceline” zones – the areas closest to heavily polluted factories and plants – and they are almost twice as likely as white people to live near chemical facilities, the Center for Effective Government found in a January report.

The sulfur dioxide case is raising similar concerns of race- and class-based injustice in River Rouge and neighboring suburbs, where over half the population is black. The metro Detroit area is considered the fourth top “asthma capital” in the U.S., the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America found in a 2015 survey of the most challenging cities to live in for asthmatics.

“We need to make sure that Detroit is not the industrial dumping ground for the rest of the state and region,” says Dr. Abdul El-Sayed, executive director and health officer of the Detroit Health Department. “The lives of these folks matter just as much.”

The bulk of Wayne County’s SO2 emissions come from just two sources: DTE Energy’s coal-fired power plants in River Rouge and Trenton Channel.

Brian Corbett, a spokesman for the utility, says that DTE Energy “always has and will continue to meet all local, state and federal emissions regulations.” He adds the fact that its two power plants are in the EPA nonattainment zone doesn’t mean air quality there has deteriorated, but rather “that the new standard is significantly stricter than the previous standard.”

DTE Energy, based in Detroit, has around 2.1 million electricity customers and 1.2 million natural gas customers across southeastern Michigan. The company has invested more than $2.2 billion on emissions control equipment in the past decade, which has helped to lower its SO2 emissions by 62 percent, nitrogen oxide emissions by 51 percent and mercury by 37 percent, according to the utility.

Corbett said it’s too early to say how Michigan’s plan to curb SO2 emissions would affect its power plant operations in Wayne County. “We are working with DEQ and with other parties who are contributing SO2 to the area, so hopefully we can resolve this issue,” he said.

The DEQ doesn’t have a deadline for submitting its draft proposal to the EPA. Bob Irvine, the DEQ supervisor overseeing the plan’s development, said the agency is working to get DTE Energy and other emitters to agree to additional SO2 reductions. “We’ve gotten cooperation in some cases and not so much in others,” he said. “We’re trying to do the best we can to relook at everything.”

Vicki Dobbins, the River Rouge resident, says she doesn’t want to wait for state and federal regulators to figure it out. Money is tight for the substitute teacher, but she says she hopes to move to another town where the air is cleaner and easier on her lungs.

“I’m trying to figure out a way that I can get away from this area,” said Dobbins.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.