Mideast Mothers Count Days To Biden, Visas To See Children

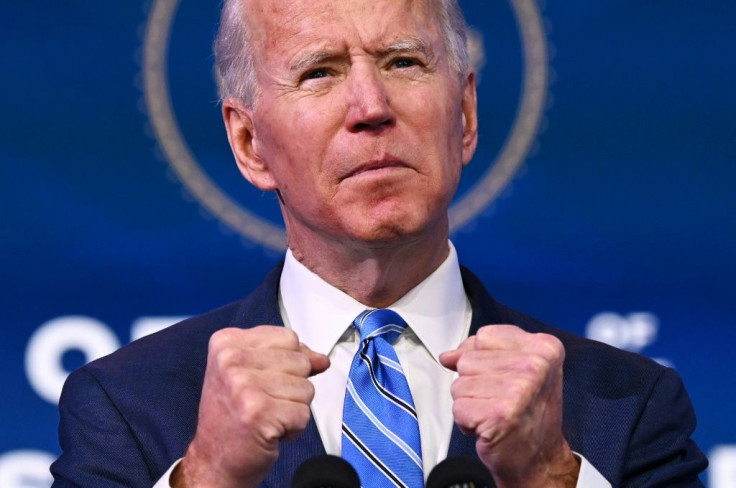

Syrian mother Dahouk Idriss says she can't wait for US President-elect Joe Biden to be inaugurated Wednesday, so she can finally visit her son for the first time in four years.

Biden has pledged that, on his first day in office, he would reverse a ban ordered by Donald Trump on travel to the United States for citizens of many mostly-Muslim countries.

"I'm counting the days until I get my next visa," Idriss told AFP, sitting in her comfortable Damascus living room, surrounded by pictures of her far-flung children and late husband.

The retired chemistry teacher in her sixties said she visited her 36-year-old son twice after he started studying in Washington DC the year Syria's war broke out in 2011, once in 2015 and the last time in late 2016.

But after Trump took over the White House in 2017, he banned access to the United States to all travellers from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen, igniting international outrage and leading to domestic court rulings against it.

Iraq and Sudan were dropped from the list, but in 2018 the Supreme Court upheld a later version of the ban for Iran, Libya, Somalia, Syria and Yemen -- as well as North Korea and Venezuela.

Idriss slammed the ban as "outrageous".

"Thousands of mothers like me around the world only have one wish, which is to see their children again," she said.

That should be possible for many under Biden -- at least once the separate international travel restrictions imposed due to the coronavirus pandemic ease.

That may take some time, however, with Biden's team declaring Monday that "with the pandemic worsening, and more contagious variants emerging around the world, this is not the time to be lifting restrictions on international travel".

To travel anywhere from Syria has become increasingly difficult since the war broke out as many countries severed ties with Damascus.

Obtaining a visa often requires a trip to an embassy in a neighbouring country, which has been made even more difficult by Covid-19 restrictions.

But Idriss, who has also struggled to visit her daughter in the United Arab Emirates, says she will jump through as many hoops as necessary to see her son again.

"I will travel to any country to submit my documents as soon as they start accepting applications," she said.

In another part of Damascus, 79-year-old Lamees Jadeed said she too hoped Biden would keep his promise.

"It's been more than four years since I last saw my daughter," she said. "I'm scared I'll die alone without seeing her.

"I'm probably more impatient for Biden to become president than he is himself."

Her daughter, 38-year-old Nawwar, travelled to the United States on a scholarship in late 2015. She has since applied for asylum and therefore cannot leave the country.

Jadeed says she travelled once to Lebanon in 2018 to request a visa at the US embassy there, but was rejected.

Elsewhere in the Middle East, other parents too are waiting with bated breath.

In the Libyan capital Tripoli, Mariam and Abdelhadi Reda, both in their late seventies, said they could not wait to see their three grandchildren again.

Since the ban in 2017, they have managed to reunite in Turkey, at great expense due to the extra flight tickets and hotel bills.

"This travel ban is so unfair and totally unjustified," said Mariam, a retired English teacher.

Their daughter Elham, a 49-year-old nurse, lives with her family in Detroit, Michigan.

She was born in the United States after her parents travelled there to study on a scholarship from the Libyan government when they were younger.

"I miss the States," Mariam said in Tripoli. "We have very good memories and old friends from our college years that we see every time we go back."

In Iran, retired midwife Mahnaz, 62, recounted how she was not allowed in 2018 to be by her daughter Neda's bedside when she gave birth to her first child in Los Angeles.

"It was my first grandchild. I had been waiting to live this moment with my daughter. How I had dreamt of it, and made plans," she said.

With no US embassy in Tehran after the two countries severed diplomatic ties in 1979, she travelled to neighbouring Armenia, hoping to be able to obtain an exemption from the ban.

"I even provided a letter written by an American psychologist saying my daughter needed emotional support," she said.

But despite the promises of an understanding embassy employee, her demand was rejected.

She did not meet her grandson Kian until nine months later when her daughter returned to Tehran to visit.

"This ban has ripped so many families apart," Mahnaz said.

"The person who ordered this is not a normal person and has had zero regard for the human consequences of his decisions."

"I cannot wait for Biden to arrive and annul this law."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.