Mine Waste Finds New Life As Source Of Rare Earths

Sweden, South Africa and Australia are at the forefront of a push to transform piles of mine waste and by-products into rare earths vital for the green energy revolution, hoping to substantially cut dependence on Chinese supply.

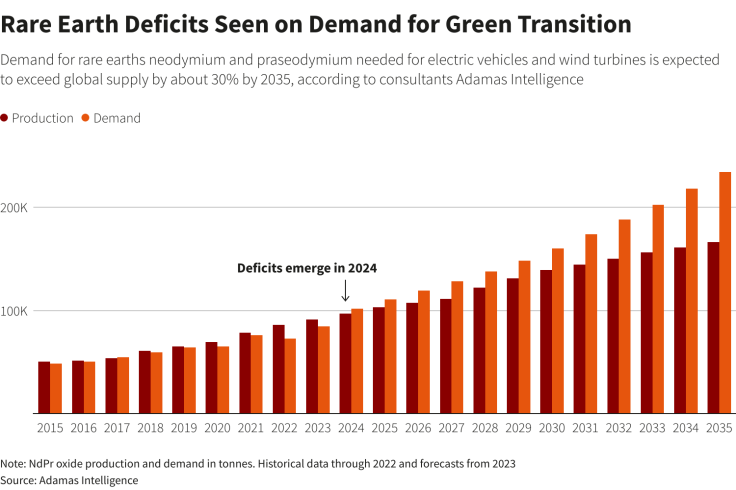

Prices of the minerals used in products from electric cars to wind turbines have been strong, and a rush to meet net-zero carbon targets is expected to further boost demand.

Europe and the U.S. are scrambling to wean themselves off rare earths from China, which account for 90% of global refined output.

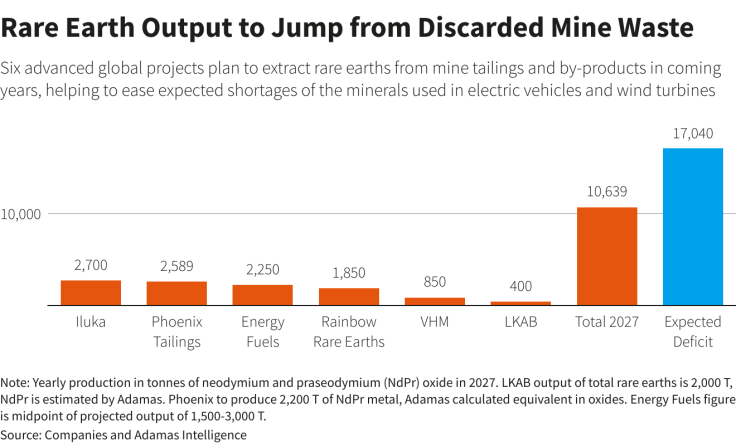

Six advanced projects outside China, including one operated by Swedish iron ore miner LKAB, are now being developed to extract the materials from mining debris or by-products.

Australia's RMIT University estimates there are 16.2 million tonnes of unexploited rare earths in 325 mineral sands deposits worldwide, while the U.S. Idaho National Laboratory said 100,000 tonnes of rare earths each year end up in waste from producing phosphoric acid alone.

The six projects, processing material from mineral sands, fertiliser and iron ore operations, are targeting output of over 10,000 tonnes of key elements neodymium and praseodymium (NdPr) oxide by 2027, analysis by Reuters and consultants Adamas Intelligence showed.

That, Adamas says, is equivalent to some 8% of expected demand for the two rare earths, vital for making permanent magnets to power EV and wind turbine motors.

Potentially they will cut the expected deficit in the materials by upwards of 50%, data from Adamas and the Reuters analysis showed.

"These projects are the low-hanging fruit in the supply chain at the moment," said Ryan Castilloux, managing director at Adamas.

"There's more demand growth coming in the near to medium term than production, so there's an opportunity for these readily accessible sources of supply."

Rare Earth Deficits Seen on Demand for Green Transition,

Rare Earth Output to Jump from Discarded Mine Waste ,

QUICKER THAN NEW MINES

Recovering rare earths from waste is much quicker than setting up new projects from scratch. A new mine that state-owned LKAB is planning to develop at Europe's largest known deposit of rare earth oxides could take up to 15 years to launch.

In contrast, its project to isolate rare earths from byproducts from two existing iron ore mines in northern Sweden is due to kick off in four.

Material from an initial stage of iron ore processing, which is currently deposited in a tailings dam, will be retained and go through further treatment stages.

"We want to make sure we extract as much value as possible, and when we come to the critical minerals, we have those in our ores already," said David Hognelid, LKAB's chief strategy officer for special products.

The company will extract phosphorus for fertiliser, fluorine and gypsum in addition to rare earths.

In South Africa, Rainbow Minerals is also planning to process stacks of waste from years of phosphate mining.

But the biggest such project is in Australia, where mineral sands producer Iluka is gearing up to process 1 million tonnes of stockpiled by-products that have been building up at its Eneabba site since the 1990s.

It is building a rare earths refinery due to open in 2025 that together with related infrastructure is expected to cost between A$1 billion ($677.1 million) and A$1.2 billion, helped by a government loan.

NEW TECHNOLOGY

A key element to making new projects viable is technology developed to separate the rare earths.

Rainbow Minerals will use a new process developed by U.S. company K-Technologies based on ion chromatography, which is common in the pharmaceutical industry and other sectors.

LKAB will be sending its material for separation to Norway's REEtec, in which it is the biggest shareholder.

Commodity trader Mercuria also bought a stake in REEtec for a new division that targets metals needed for the energy transition.

"REEtec fits the narrative of building processing capacity for rare earths in the part of the supply chain where we think there's a bottleneck," said Guillaume de Dardel, head of energy transition metals at Mercuria.

"The company's technology has a lower environmental footprint compared to the legacy solvent extraction process essentially used for rare earths separation in China."

In the U.S., Phoenix Tailings, funded mainly by venture capital funds, is using new technology developed by scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

"There's zero waste, zero emissions and we're also doing it competitive with Chinese prices. We're not going to rely on government to fund us," said Chief Executive Nick Myers.

Prices of rare earths have climbed in recent years, making new projects more viable. Those of NdPr alloy in China, while down from a peak seen last year, have nearly doubled over the past three years.

($1 = 1.4769 Australian dollars)

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.