Minimum Wage Increase: Naquasia LeGrand, KFC Employee, Says Fast-Food Workers Need Better Pay, And Companies Like Yum Brands (YUM) And McDonald’s (MCD) Can Afford It

Earlier this week, Naquasia LeGrand was working the closing shift at a KFC restaurant in Brooklyn’s Sunset Park neighborhood. On Thursday, she was en route to Washington, D.C., to meet President Barack Obama.

It has been an interesting year so far for the 22-year-old union activist, a member of the Fast Food Forward movement that’s calling on fast-food companies to pay their employees a starting wage of $15 an hour. After participating in five strikes backed by the Service Employees International Union and the local NY Communities for Change group, LeGrand has become New York City’s face of a growing national movement that underscores the discord between how much millions of fast-food workers in the country earn compared to how much it costs them to live in the United States.

Before traveling to the White House on Thursday, she made an appearance on Comedy Central’s “The Colbert Report” to deliver her message to the show’s largely sympathetic audience. In an interview with the L.A. Times last year, LeGrand described how she became a labor activist after hearing so many stories from co-workers describing how difficult it was to pay the bills. In a city where $1,500 for a one-bedroom apartment is considered a bargain, it’s difficult to comprehend how service-sector employees being paid even 20 percent to 30 percent above minimum wage can make it here.

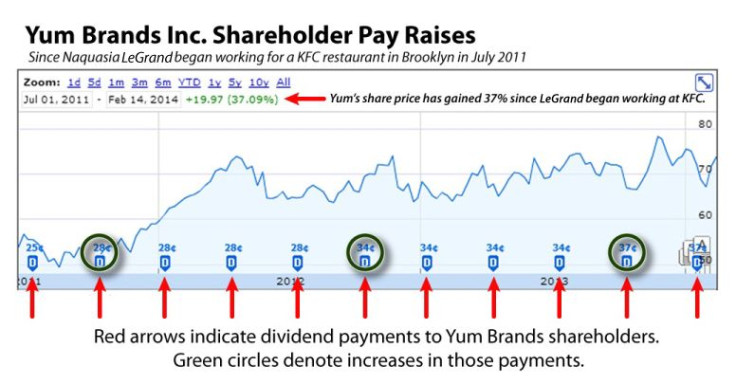

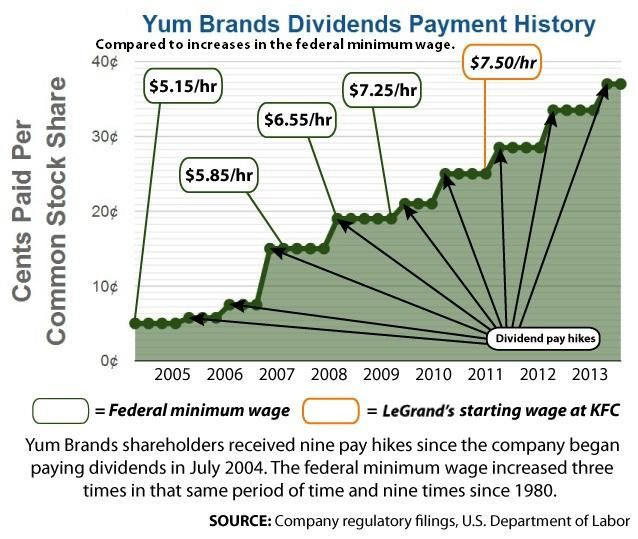

LeGrand pulls down $8 an hour, a little more than 9 percent above the federal minimum wage. She draws that income not because of the wage policy at the Kentucky-based corporation that owns KFC, Yum Brands Inc. (NYSE:YUM), but because of changes to New York state’s minimum wage law that went into effect on Jan. 1. Before January, LeGrand was making $7.70 an hour. The job was a "detour" between high school and that computer degree she was hoping to get someday, but she stayed, working 16 months before receiving her first wage increase, of 20 cents, and that only after she and others participated in a one-day strike. Now she's coming up on three years at KFC.

There are currently about 8.1 million people in the U.S. working in food preparation and serving-related occupations who make a median wage of $8.98 an hour, according to the U.S. Department of Labor. About 3 million of these workers are fast-food cooks and counter employees, who on average make the lowest wages in the U.S. food services industry.

As part of the White House’s effort to get Congress to act on raising the national hourly wage floor from its current $7.25, President Obama on Thursday signed an executive order requiring any business that wins a federal contract to pay its employees a minimum of $10.10 an hour. On the invitation of the White House, LeGrand joined Dawn Moore, a Chicago-area McDonald’s employee, and other low-hourly-wage workers from Pennsylvania, Delaware, Virginia and elsewhere to meet the president and to attend the House Democratic Retreat in Cambridge, Md.

The president’s executive order to raise the floor on wages paid by federal contractors is aimed at spurring action by Congress to raise the federal minimum wage. The move has been hailed by supporters and decried by detractors in the incessant back-and-forth bickering that comes every time the topic arises. The liberal side says $7.25 is unrealistically low considering the cost of living in the U.S., while the conservative side says any increase in the minimum wage will cause employers to cut hiring.

What's not a matter of debate is that when baby boomers (liberals and conservatives alike) were taking their first jobs – such as flipping burgers or frying chicken – in the early 1970s, the minimum wage was $2 an hour. To match that same spending power today, the minimum wage would have to be between $9 and $10 an hour. And this doesn’t account for the steep increases in the cost of health care services and education that have cut millions off from accessing affordable preventative medicine and higher education without government assistance. To put it bluntly: The people running the government today made more money in their first jobs and spent less on health care than people joining the work force today. And that matters.

LeGrand agreed to sit down with International Business Times recently to talk about her circumstances and to discuss why she decided to join Fast Food Forward to demand higher pay for the people who take your orders and prepare your food and help bring in billions in profits to the world’s largest fast-food corporations, which deliver regular dividend checks to their shareholders.

The interview took place across the boulevard from LeGrand’s apartment in Canarsie, which is situated in an cluster of old multistory apartment buildings once inhabited by Russian Jews but now exclusively occupied by African-Americans. LeGrand shares a two-bedroom flat with her grandmother, aunt and young cousin. A couple of blocks from there are the placid waters of Jamaica Bay. A mile in the other direction is the closest subway stop.

IBTimes: You were saying earlier that you closed the restaurant last night. Is it close to here?

LeGrand: No. I have to take a bus and three trains [subway connections] to get to where I work. It’s in Brooklyn, but it’s near Park Slope, in Sunset Park. I’m here in Canarsie. It’s a 20-minute walk to the train [which I take] if the bus is taking forever.

IBTimes: What’s that commute time?

LeGrand: It’s about an hour and 20 minutes.

IBTimes: Two hours, 40 minutes, round trip?

LeGrand: Yeah. I bet you’re wondering how I got that job.

IBTimes: Of course.

LeGrand: A good friend of mine works at a glass company near the KFC store. I used to go with him and do some work at the place. I would go help him and do some glass removal. I learned how to take apart glass doors. He would pay me a little something, like $20, $30, to help. He knew I was determined to find something. I walked down the block [and found the KFC job].

IBTimes: And you couldn’t get a job at the glass company?

LeGrand: I asked him how he got the job. He had a lot of experience. Everyone there had a lot of experience. I really did push that issue because I wouldn’t have minded doing glass. It was pretty fun. It was a good learning experience. I wouldn’t mind finding a little class or something. I would do it.

IBTimes: So you have your mind on getting out of KFC.

LeGrand: Of course! I’m going on three years in July. I’m blessed to have the job and I learned something about working with food and dealing with customers. I was a prep cook at the airport before, so I already knew a little about how to deal with food. It has been a good learning experience, but there have been a lot of issues. I was coming into this job at a certain time in my life where I was just tired of New York. I wanted to move down south [to North Carolina] to where my mother lives. I planned it and everything.

So I went to my new manager who had just come in. By the time she arrived, they were still training me to be a supervisor. The only thing I was waiting for was a food safety and supervisor class, but I had been training already for six months. Why was I still waiting for this class? They kept saying the classes had been pushed back. This was before my first strike. I had this new manager who knows I had been training for months. I’m pretty much showing her how to do the job.

IBTimes: So they were giving you the promise of advancement and better pay but not following through?

LeGrand: I was doing manager work, counting inventory, counting money, making sure the chicken was dropped [in the fryer] at a certain time. I was doing everything a manager does, for $7.50 an hour.

IBTimes: How much does a manager of this store make?

LeGrand: I don’t know for sure. The GM is probably making a little over $500 [a week] and the assistant manager, probably a little over $400. That’s why I always say to my co-workers that even our manager knows what we’re doing is right, it’s just that the way she’s acting is coming from up top. This is a pyramid, the manager, the district manager, the head of operations and the owners of the corporation.

IBTimes: During your appearance on "The Colbert Report," host Stephen Colbert asked why you don’t just work more, get more hours, if you need more money. You said, “Ask my manager that.” Do you feel that your union activism has led to soft retribution, getting your hours reduced? Or is this something the employer is doing to everyone at work?

LeGrand: In a way, I would say yes, but at the same time, I feel like this is just the way this manager manages her store. When I went on my first strike, this manager had just come to the store. She was a two-weeks-old manager. The manager before, I don’t know if she even knew what was going on. The first strike [in November 2012] was underground. They didn’t know what was going on. We just popped up, like “We going on strike.” At the same time, my managers had switched. The new manager was already making changes to the schedule. She began hiring new people, but how could you hire more people if you’re telling your workers you don’t have enough hours [for them]?

IBTimes: There have been reports in the media of some large companies reportedly keeping many hourly workers under 30 hours a week so that they aren’t eligible for health insurance benefits. Is this scaling back of hours and adding more employees, is that affecting everyone’s ability to get more than 30 hours a week at the restaurant?

LeGrand: Yeah, definitely. It sounds crazy, but some people get 30 hours under the table. They put the work schedule up. Everybody on the schedule will have 20 hours here, 15 there, 16 hours here. Later, they pick people to work more hours. But instead of calling somebody who already has 24 hours for the week, they call the person who has 12 hours. The previous manager, she was giving more hours based on work ethic. And at the time there wasn’t that many people working at the store. So I was getting 35 hours a week.

IBTimes: It sounds like they brought in more part-time employees and reduced most employees’ weekly schedules to below 30 hours.

LeGrand: Right. Why 30 hours [to make you eligible for health benefits]? Why couldn’t it have been 10 hours? And that’s another thing about these corporations. You want to pay me minimum wage, great. But you don’t want to provide health insurance either? Something’s got to give. Since you don’t want to give, we gotta fight.

IBTimes: Is there a lot of employee turnaround?

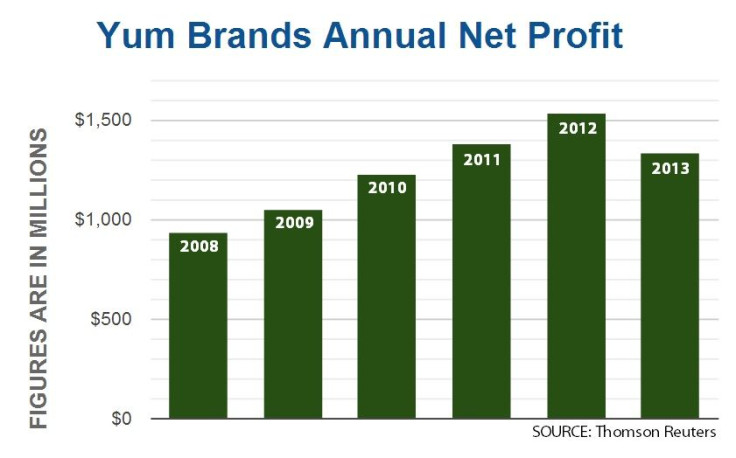

LeGrand: You mean people quitting? No. People hang on because it’s hard to up and quit a job if you don’t have nothing else to go to. That’s one thing that stops workers [from joining strikes]. It’s not like we want to be at KFC or McDonald’s or Burger King forever. We gotta do what we gotta do in order to survive, in order to make sure our families have food in their mouths and clothes on their backs—something to sustain us until we do find something better. But how long before I can find something else? That’s one of the reasons why we workers believe we do need more from these companies. These companies have it to give.

IBTimes: You said you started at this store in July 2011, at $7.50 an hour. How long did you work before you received your first raise?

LeGrand: My first raise was after my first strike in November 2012. After my first strike, I got a 20-cent raise, so then I was making $7.70 an hour. It went up to $8 an hour on Jan. 1 [as part of changes to the state’s minimum wage law].

IBTimes: Last year the Los Angeles Times wrote about you and focused on how the Service Employees International Union played a role in your activities. Companies like Wal-Mart have really lashed out at this type of relationship, accusing unions and outsiders of rabble-rousing inside a largely satisfied company workforce, trying to force workers to pay union wages. What do you say to critics who accuse unions of creating moles and unrest among a small number of unsatisfied employees?

LeGrand: So, yeah, they say I’m pretty much a clone, like they’re cloning me. This is what I say to that: No. Because at any given time, I could have said, “Forget this campaign; I don’t want to do this.” It wasn’t up to the union. What they gave us workers was a foot to get in the door. We didn’t know how to get a foot in the door. The union gave us the light to see what was really going on behind the counter. Single moms and single fathers are struggling while these companies make money, and we’re not really paying attention as workers because we’re too busy working and not thinking about these things.

And these things that are coming to light are true. And that’s why these companies are mad and calling us moles. They don’t want us to know the truth. They want us to be stuck in the dark, living in poverty. That’s not right. What I say is I’m standing up as a hard worker who appreciates her job, who is grateful for my job, but who is also standing up for me and other workers who believe that we deserve better pay and the right to unionize without retaliation.

IBTimes: You had mentioned before that your family had mixed feelings about your decision to become a fast-food workers union activist.

LeGrand: I really didn’t know what a union was. I always heard people talking about it, but I still didn’t know how you got in there, or how a union comes about. So I started doing my own research and that’s how me and my grandmother bumped heads. I asked her, “Are you in a union?” And she’s like, “Yeah.” She works for the post office. But she was looking at me like, “I don’t know about this. That doesn’t sound like a good idea.”

IBTimes: She was worried you would lose your job.

LeGrand: Yeah, she was worried about that. She was like me. She didn’t know what was going to happen. I listened to her, and she had me a little worried, too. But I also went to my aunt, and she’s in a union. She works for Verizon. I was talking to her and she was like, “Yeah.” She was all for it. When I started telling my grandmother I was going to meetings, we bumped heads some more.

IBTimes: How does someone survive on $8 an hour in this city?

LeGrand: Me, my grandmother, my aunt and my little cousin live in a two-bedroom apartment. The rent is $1,300. When I started, I was getting about 35 hours a week, when I was training to be a supervisor. That went on for months even before the new manager came in and started cutting hours and hiring more people. Right now I’m only getting about 15 hours a week, [so] I’m taking home about $100 a week.

IBTimes: So three adults and a child in a two-bedroom apartment in deep Brooklyn, where it takes an hour and 20 minutes to get to an $8 an hour job…

LeGrand: That's how most of us are making it. You can’t live in this city by yourself.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.